“From the moment I touched heroin, I felt as if I’d joined forces with the devil. I went from being unbeatably lucky to becoming a powerful foe — my own worst enemy. I had opted for self-destruction.”

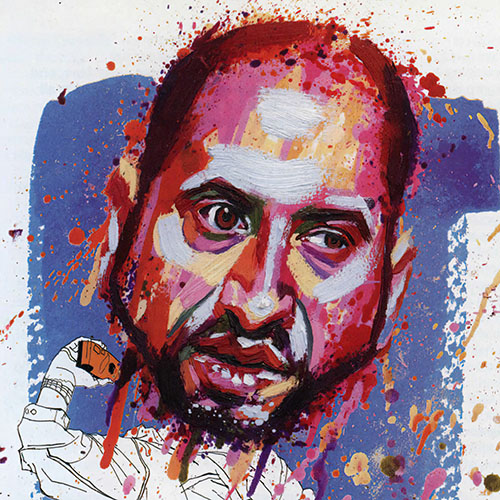

Pete Townshend: The Penthouse Interview

Throughout the winter and spring of 1981, British music circles reverberated with news of Pete Townshend’s repeated transgressions. The lead guitarist and chief composer for the Who rock band was said to be drinking his breakfast and popping pills as if they were children’s gumdrops. After gaining international recognition for his pioneering rock operas Tommy and Quadrophenia, Townshend now seemed to be sinking ever deeper into drugged oblivion. At London’s trendy Soho clubs, he became the instigator of countless shouting matches and fights. Then there was the disastrous concert that March at the Rainbow, where the musician incensed the rest of the band by launching into long discordant codas and improvising on the spur of the moment. By the fall, gossip columnists had begun spreading rumors about his flirtations with heroin. There was even talk about one sordid night at the Club for Heroes, a New Romantic venue, where Townshend collapsed on the verge of death.

Pete Townshend’s close associates watched his metamorphosis from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde with both confusion and concern. Why should the voice that had belted out such fiery teenage anthems as “My Generation” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” suddenly falter? How could the fist that had banged out electrifying guitar riffs become the perpetrator of senseless barroom brawls? Why had rock’s spiritual leader become so dispirited?

Whatever personal horrors had triggered this crisis, Townshend was unquestionably back in form by the time the Who began its final farewell tour of North America last autumn. For the 1.2 million fans who attended the forty concerts, the wayward rock star appeared to have been restored to all his former glory. Stirring the crowds to a frenzy, Townshend bunny-hopped across the stage and, without missing a beat, executed one dazzling leap after another. Flailing his guitar in the dizzying, whirligig strokes that had become his trademark, the thirty-eight-year-old musician displayed the same gusto that marked his early performances at the Marquee Club, that steamy dance hall where the Who first captured the hearts of a generation nearly two decades ago. Only this time around, there was none of the sloppiness — the bad notes or ill-timed overtures — that had so often marred their youthful deliverance. The band was tight, demonstrating a flawless virtuosity almost unprecedented in its eighteen-year career.

Back at the hotel room after the concert, Townshend confirmed that he was off drugs. He looked trim and fit. Only his jaded blue eyes, windows on a frazzled soul, hinted that some scars remained. Despite the dramatic upswing in his life, it was clear that the turbulent past continued to weigh on his conscience. Having only narrowly escaped the same fate as the Who’s late drummer Keith Moon, who died of a drug overdose in 1978, Townshend was grateful to be alive. And so he spoke at great length about his miraculous salvation.

Miraculous, in this instance, may be an understatement, for the cure Townshend underwent seems to have reversed two years of dissipation in ten days. The secret behind his startling rebound, he divulged, is NeuroElectric Therapy (NET) — a novel method of detoxification that is currently awaiting clinical approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This unusual treatment involves a Walkmanlike device that transmits a tiny electrical signal to the brain via electrodes taped behind either ear. Townshend wore this portable gadget — or the “black box,” as he nicknamed it — day and night during the initial phases of treatment. He claims that it rapidly cleansed his body of drugs without the painful withdrawal symptoms that usually make going “cold turkey” such an unbearable ordeal.

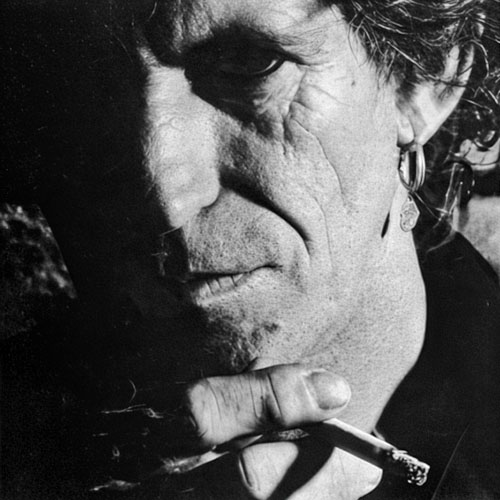

The black box is the brainchild of a middle-aged Scottish surgeon, Dr. Meg Patterson. Her explanation of its scientific rationale provides insight into the experience of her celebrity patient. According to Patterson, who is something of a celebrity herself among the higher echelons of rock management, the black box quickly redresses chemical imbalances in the addict’s brain. She believes the weak current stimulates the production of various neurotransmitters, notably the brain’s own opiatelike painkillers, the endorphins (for “morphine within”). Because the frequency of the electrical current appears to determine which chemical reactions will occur, Patterson has to fine-tune the signal for each type of addiction. With Townshend, who suffered from multiple addictions, she applied several different frequencies over the course of treatment. Her remedy appears to have worked, for the disheartened musician experienced what can only be described as a rebirth. And his case is by no means unique. Townshend himself first learned of NET through blues guitarist Eric Clapton, whom Patterson weaned from heroin in 197 4. Since then, she has successfully reformed over a dozen top recording stars, including such notorious drug abusers as Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones. Townshend felt compelled to speak out about Patterson’s work both to repay a personal debt and to draw attention to her enormous behind-the-scenes contribution to the music industry as a whole.

Of course, some psychological problems remained, and in the interview that follows, Townshend talks with disarming candor about the difficulty of facing up to his own failings and the even greater challenge of healing badly strained relationships with his family, friends, and members of the band — bassist John Entwistle, vocalist Roger Daltrey, and drummer Kenney Jones. But for the most part, the nightmare had ended by the time he talked with Omni magazine editor Kathleen McAuliffe in the fall of 1982.

McAuliffe told us, “Certainly in the artistic arena, there were abundant signs that his life had come together. Not only had the Who’s final tour received rave reviews in the music press, but their latest album, It’s Hard, had been hailed as their most powerful work since Who’s Next. Townshend’s two solo albums, Empty Glass and All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes, released two years later, had also won broad critical acclaim.”

“These recent successes, however, seemed less important to Townshend than the need to put his past in perspective. Yet his frank disclosures, he later confided, served no cathartic purpose. He was trying to share, not shed, his immediate past, presumably so that others might learn from his experience.”

What do you think led you to seek refuge in drugs in the early eighties?

Pete: Some of my problems were rooted in my inability to deal with the band. I felt that the band wasn’t facing up to reality. I should have said to the band, “I’m leaving. I’ve had enough of rock ’n’ roll. Goodbye.” But I didn’t. I couldn’t deal with that emotionally at the time.

I had money problems as well. Through incredible mismanagement of my companies in Britain, I became very deeply in debt to several banks — about one million dollars in debt. When I realized that I couldn’t earn a million dollars after tax in a year, I started to go round and round in circles, getting very upset at the idea of having to sack people.

What made things even worse was the long period of sustained touring that the band did immediately after my first solo album, Empty Glass, came out in 1980. We did about four months’ work spread out through a year. I wasn’t home very much, and when I was, I hit the bottle heavily. My wife and I grew more and more estranged until eventually there was nothing really there, apart from my relationship with my children, which I maintained as much as I could.

We decided it would be best if I went to live in a hotel or in my club in London. I did that and soon I became involved in a much higher level of promiscuity than ever before. It was not through any increase in appetite. I was just so socially demented all the time that I didn’t realize what I was doing. I was very gullible. When I was on the road, I would often wake up in the morning with a roomful of girls whom I’d never seen before, simply because I had been so drunk the night before that I didn’t throw them out or politely ask them to leave or whatever it is that you do.

At what point did you find yourself turning more and more to drugs?

Pete: About midway through 1980 I made the mistake of starting to use cocaine. I became immediately dependent upon it because I loved the feeling of it so much. I’m very much a stimulants kind of character. It also helped me cut through the drunken haze. You sober up when you have a toot, drink more, have another toot, sober up, and of course you repeat the cycle until you’re too wrecked at the end of the day to go on.

I got used to behaving very badly. Once I was so completely out of my brain that I actually humiliated the band in public. We were playing at the Rainbow in London — this was early 1981 — and I kept stopping songs and making speeches to the audience. I kept playing long, drawn-out guitar solos of distorted, bad notes. I’d alter the act, making up songs as I went along. And I knew it was London, and I knew that everybody’s friends and family were there, and I deliberately picked that day to fuck up the show. I just ceased to care. I threw my dignity away.

Everything got increasingly worse until about June or July of 1981, when I was making my second solo album. I had to stop making it, because I literally couldn’t work. I was becoming exhausted through being in a recording studio.

This really got to me, because rock ’n’ roll should be all fun, all pleasure. There’s quite a lot of guff talked about the pressures and the rigors of the road, but if people don’t like it they shouldn’t do it. It’s not happiness that you’re seeking. It’s pleasure. Pleasure through music, highs, euphoric feelings — all these extremes. I couldn’t stand this fucking feeling of being wrecked all the time, and feeling that I was going to be sick.

Did you seek professional help?

Pete: I went to this doctor and he prescribed some sleeping tablets, some high-power vitamins, and an anti-depressant, or tranquilizer of sorts, called Ativan. [Ativan is chemically a close relative to Valium and Librium.] Now these Ativans were really the business. They made me feel incredibly good. I felt as if I could cope with everything. So about a month before Christmas, I decided to go back into the studio again. And there was this French woman hanging around all the time, and she asked me, “Have you got any junk?” And I said, “No.” And she said, “Well, how the hell are you managing?” So I said, “Managing what?” I suddenly cast my mind back and I remembered a series of events that had happened to me throughout the year. The most notable incident was being carried out of a nightclub and taken to a hospital with a drug overdose. I had not been able to remember the circumstances except that, when I got to the hospital, a nurse found needle holes in my arm.

After this happened, I rang up a friend of mine who was a dealer in cocaine. Incidentally, he is now dead at twenty-six years of age. He died of an OD last week, just before I came away. Anyway, I rang him up and asked him, “Have we been doing any, you know, smack?” And he said, “Yeah. Sometimes I put a bit in with the coke, but not enough to cause any problems.” But you see we’d been doing a lot of freebasing …. So when the Ativan stopped working, and I turned to heroin, it did not take long for me to become well and truly hooked. I just sort of topped off a habit, I guess.

But why the track marks?

Pete: I only later, discovered the significance of that. In the nightclub that evening, a so-called friend of mine in the music business said to me, “You look really smashed.” I said, “Yeah, I am.” He said, “I’ve got something for you.” And he took me in a toilet and gave me an injection of heroin. Apparently, I had used heroin in front of a few gossips one night, and word had gotten around that I was a heroin addict. So this guy thought I was suffering from withdrawal and that he was doing me a favor, when in fact I’d simply had too much to drink. Anyway, the shot of heroin temporarily killed me — my heart stopped. When they carried me into the hospital, I was dark blue. The nurse actually had to rip off my shirt outside the hospital and beat me back to life.

You certainly managed to pack a lot of drama into those years.

Pete: Yeah. And it’s only recently that I’ve gotten all the details. I was doing all these things that were completely at odds with everything about me and what I stand for. Yet at the same time, everything somehow seemed comfortable and normal to me. It’s strange, but when I’m in league with God, I’m incredibly lucky, blessed, graced. From the moment I touched heroin, though, I felt as if I’d joined forces with the devil. I went from being unbeatably lucky to becoming a powerful foe — my own worst enemy. It was as if I had opted for my self-destruction. It finally dawned on me that heroin was a very bloody adversary, and that I had to be prepared to lose my life in order to gain it again. It was at this point that I got the idea to ring up Meg [Patterson] in California and ask her what I should do. She insisted that I fly out the next day, which I did, and three days later I was straight.

I have to confess to being a little confused. What precisely were you addicted to at this stage? Was heroin your primary addiction?

Pete: I suppose a month before I got NET, I’d been freebasing two or three grams of coke, which required about half an ounce of coke to produce; I was smoking about one gram, sometimes more, of heroin; and on top of that I was usually taking about eight to ten Ativan tablets plus two or three sleeping tablets to get to sleep at night — I was a walking pillbox. Yet somehow I managed to come through all of this with my brain still intact, with enough common sense and dignity to reestablish my family. And by reestablish my family, I mean I was allowed back, as it were. I had to acknowledge everything that was wrong with my life. What had gotten me into so much trouble to begin with was my refusal to face up to various problems. So one of the first things I did after getting back was deal with the bank.

How did you manage that?

Pete: I gave them my record contract and said, “Listen, hold on that. Don’t charge me any interest. I’ll get on with delivering the record and you just take the lot. I’ll pay you over three or four years.” I also sold a lot of assets. I closed my bookshop and sound-equipment company. I sacked a few people. I raised the rates at my recording studios. I cut down on personal spending. I sold my Ferrari and my boat.

I also managed to convince the guys in the band that I would stay alive if they allowed me to work with them again. After the Rainbow fiasco, I had difficulty proving to Roger in particular that I was going to enjoy working with the Who, and that it was important to me that the band end properly, rather than end because of my fucking mental demise. I love the group. What I couldn’t stand was the tension of not knowing when it was going to end. I just had to know when it would finish — I couldn’t stand the indecision. So we agreed to wind everything down between eighteen months and two years from that time.

Have you repaired your relationship with the other band members?

Pete: As much as it’s possible. They’re probably not over-delighted that the band will stop working because it suits me and Roger — I don’t know about John and Kenney. To maintain my own stability, however, I know I’ve got to face up to things. Before I wanted to be popular with people, and I’d try to do whatever they wanted me to. But I now realize that it’s sometimes necessary to be ruthless with money, with business, and about how I spend my spare time. In particular, I have to be very careful about my tendency to overwork. I really know how much I’m capable of now.

“I think possibly the only reason why I managed to achieve anything at all was because the people around me were being very, very well paid to put up with it.”

That treatment seems to have worked wonders for you. How does it work?

Pete: I think NET is a fairly simple thing. It restimulates the brain to produce endorphins. The theory is that the brain stops making its own opiates if you take heroin. You see, drugs literally barge their way in and grab hold of the receptors [active sites on brain cells that the endorphins normally occupy]. Drugs wreak havoc where there was once peace and harmony. So with NET, you use an electrical frequency that will restimulate the problem area.

Could you describe the treatment, starting from the first day?

Pete: I took a massive dose of heroin to get to California, and the Pattersons met me at the airport in a van and they hooked me up to the machine as soon as I got in. The first frequencies they gave me were low ones for heroin. I think it was kept on that setting for about eight hours.

Did the electrical stimulation give you a euphoric buzz?

Pete: No. I just got this sense of a natural energy flowing into my body. It was as if all sorts of dormant feelings were being rekindled. The inner joy of recovery, and becoming independent from drugs, produced this tremendous feeling of rejuvenation. By the second day, in fact, I knew I was on the home stretch. And on the third day, I started to look and feel human again. I started to read newspapers and to write about the way I felt. I remember writing things like, “I want to go out for a walk. I don’t believe it.” I could really feel my passion for life returning.

Another thing was that I’d had traces of returning sexuality. Initially, that was quite troubling for me, because I’d put down a lot of my problems in relationships to an abnormally dynamic sexual appetite — and a confused sexual appetite. I’d talked to close friends about it and they’d said, “Oh yeah, well, you know, that’s pretty much normal if you’re an aggressive, high-strung individual. After all, half the people who are successful in business or acting are sex crazy.” But I suppose that for about a month, maybe two months, before being treated I’d felt no sexual feelings whatsoever, so the treatment definitely had a rekindling effect.

I think I also wrote that I was still feeling somewhat bitter, or betrayed. But then on the fourth day, I woke up with this aggressive, angry attitude toward life. No, arrogant is perhaps a better word. I believed that I could take on the world. Later on, though — on the fifth day, I believe — I started to get depressed. Meg would then turn the machine up to a high frequency for an hour or so to stimulate the cocaine-type receptors in the brain. And if it was left on too long at this setting, I would start babbling away and everything in the room would start to go woooooooo.

Like acid?

Pete: The intensification of color and sound, often in a very pretty way, was just like acid. But there was no confusion of sense channels — that didn’t happen. I really felt up until the next day, when I woke up nauseous and achy. A lot of the withdrawal symptoms had actually returned in their own shape.

So the treatment did not totally suppress your withdrawal symptoms?

Pete: It cushioned some more rapidly than others. On the second day, the battery of the bloody machine ran out, or something went wrong. We were totally unaware of this until it became clear that I was going into steep withdrawals. I got the full belt of the symptoms back — the panic, the nose-running, and fantastic cramps, particularly in my arms and legs. When they got the machine working again, I got only some of the symptoms — and they were far less severe. I got a runny nose and I did nave muscle cramps. I had acertain amount of difficulty sleeping, but it wasn’t too bad, really. I felt fairly warm. But most important of all, I got back the ability to act.

Before, when I tried to stop using heroin unaided, I not only suffered severe withdrawal but was completely unable to get out of bed, even to carry out the most minute task. If the phone rang next to my bed, it might take me ten hours to pick up the receiver. I’d be so far gone I hardly knew what I was doing. The major difference with Meg’s treatment is that you immediately get back the ability to act. I didn’t suffer from that horrible kind of paralysis.

What about coming off all those Ativans? Did that present any problems? I ask that because people hooked on tranquilizers may experience life-threatening convulsions when suddenly deprived of their drugs.

Pete: No. I didn’t have any convulsions. But, you know, Meg took my Ativan addiction even more seriously than the heroin, which really surprised me at the time, because the Ativan was, after all, prescribed by a doctor.

Did NET help reduce your craving for drugs at all?

Pete: I wasn’t aware of having any great craving until I got back into the surroundings where I’d ingested drugs in the past. When I returned to my country home, I could sense the atmosphere that existed when I left. The loneliness, the desperation — it was all in the woodwork and the way things were laid out. Then the craving for heroin was immense.

As for coke, I usually crave it only at rock ’n’ roll parties and similar situations. When that happens, either I sit there and sweat it out or else I walk away. For a while, I tried going to nightclubs, but I just couldn’t handle it. Apart from everything else, I don’t know what I saw in those fucking piss holes filled with empty people.

Returning to the treatment, what happened on days seven through ten? Did you wear the machine around the clock right up until the last day, or was it gradually phased out?

Pete: I always wore it during the day, but I stopped using it at night on the seventh day because I no longer needed it to get to sleep.

That’s very unusual, isn’t it? When going cold turkey, don’t most people complain of horrible nightmares and endless nights of restlessness?

Pete: What happened to me was extremely peculiar. When I got to California, Meg told me how she’d only recently begun using the machine at night because she’d discovered that it helped people sleep. So my first morning there she asked me if I’d had any dreams or nightmares. I said, “No, I didn’t dream a thing — unfortunately.” She said, “Why ’unfortunately’?” So I explained how I’d been working on a book of short stories for the last two years, and that whenever I ran out of ideas I would usually just write up a dream. I said to her, “I just have the most incredible dreams. They make Salvador Dali look like Richard Scarry.” She said, “Oh, you mean you want to have nightmares?” In fact, if I’m in the middle of a nightmare, I often deliberately attempt to wake myself up so that I can scribble down certain details, which I’ll use in songs or whatever. Anyway, after that she kept asking me each morning if my dreams had come back. And when I said no, she’d say, “Oh dear, let me try modifying the frequency a little bit. Now let’s see how this setting works.” I did not, in fact, have any nightmares until well after I got home. So I rang her up to tell her everything was okay and she said, “Oh good!” I still don’t know how that fit in with her research.

“There are still things that I can’t talk about and can’t face up to…. I’ve caught myself laughing at Christ on the cross — that kind of thing.”

Were you apprehensive when the black box was taken away on day ten?

Pete: Yes, I was. As a matter of fact, I got very, very minor withdrawals for the first few days afterwards. But my mood had basically stabilized by the last three days of treatment, so I guess my endorphin levels had normalized. Also, I did a lot of exercise — that was a big help. You probably know that in the process of extreme exercise, you generally raise your endorphin levels anyway. And by about my third week at Meg’s, people who had seen me taking brisk walks would come up to me on the street and say, “That’s California for you. When you first arrived, you looked dead. We gave you about half an hour. And now look at you! All you needed was a few days in California.” The funny thing was that it rained the whole time I was there.

Listen — something else happens during Meg’s treatment. I mean emotionally. When you first start to recover, you feel superhuman. You get swept away by the euphoria of the natural high and the feeling of being able to handle any crisis. The first real emotion that came back to me was anger and aggression. The feeling of I’m going to get this lot behind me. But this is where I think Meg is so clever. It seems she understood that, and in the coming month that I stayed with her, she helped me to sublimate a lot of that and balance it. In other words, not to overreact and thus swing the pendulum too far in the other direction. She constantly stressed the spiritual rebuilding I had to do, which I’m still dealing with. The importance of getting closer to my children again and, if it was possible — and at the time it didn’t look like too hot a situation — to reestablish my relationship with my wife, Karen.

It wasn’t easy having to admit where I’d gone wrong. For a long time I kept getting stuck in the same thought patterns: None of this is my fault. I only got into the music business because my father is a saxophone player and I’ve always admired him so much. My mother left me with my grandmother when I was seven years old — all kinds of crap. The guy I brought in to manage all my companies spent too much money — it’s not my fault, you know. My wife doesn’t understand the difficulties of being a rock star. I can’t deal with the road. I can’t handle the groupies. All kinds of stuff was coming out. We talked about so many things. And in the process, of course, lots of memories came back. Lots of terrifying little cameos that made me feel deeply ashamed.

Yet you can speak about them so openly right now.

Pete: Well, I’ve got a funny make-up. Basically I don’t give a damn what people think, I really don’t.

But didn’t you say before that you wanted to be popular?

Pete: Yeah, but I want to be popular with the people who know me. With them, I want to be really popular — I want to be loved. But I don’t want people to love me because I am what they might think I am. I don’t want to hide behind some phony facade. My attitude has always been: “Love me warts and all.”

So your openness has always been a basic facet of your personality?

Pete: Yeah. Well, I mean, I did have to think very seriously about whether to admit things publicly, because of the children.

They’re girls, aren’t they?

Pete: Yeah. Aged thirteen and eleven.

How did they react?

Pete: Well, it didn’t actually come into their life. But I was concerned that their friends or the parents of their friends might give them trouble. Like they might decide, “No, you can’t go and stay with Emma Townshend; her father was a junkie.” But to be honest, I’m finding that most people aren’t the slightest bit interested in my drug problems. They don’t seem to care. Or if they do, it’s because they’re glad that I’m well, happy, and back on the right path again. Still, I do feel slightly shell-shocked. I can’t help thinking that a fantastic amount of my time and energy got used up by this whole debacle.

Yet, creatively speaking, you managed to pull off an almost superhuman feat by coming out with two solo albums during that period.

Pete: It’s quite difficult to accept that there was anything superhuman about what I achieved. If anything, I think I was living at a subhuman level. I think possibly the only reason why I managed to achieve anything at all was because the people around me were being very, very well paid to put up with it. The guy who produced my record was a great person and we love each other a lot. But there was a point at which even his patience snapped.

I wasn’t dealing with anything. I wasn’t reacting to anything around me. I had actually decided at some point to become defeated. I put all my energy and my potential into my aspiration for the gutter. It still seems incredible to me that I, who un-ashamedly try to incorporate a sense of spiritual aspiration in my music, should suddenly use all my energy and finely developed talents to do the exact opposite.

Have you sought counseling or psychiatric help since you got back to Britain?

Pete: I’m seeing a psychiatrist on a week-to-week basis, which has helped a great deal, because I can talk things out. Still, there are things that I can’t talk about and I can’t face up to. I’ve already partially unearthed these things unwittingly during dreams and through my writing. I’ve seen the color, as it were, and it worries me a bit. There are great satanic touches to these images. I’ve caught myself laughing at Christ on the cross — that kind of thing.

Do you feel your music has served a therapeutic function in your life?

Pete: I think it’s been therapeutic to the extent that I’ve been subject to such intensely pleasurable experiences in my work. You get this high from playing music that is incredibly natural. Especially when playing in public, you get the most incredible feeling of euphoria.

I wonder if that feeling of euphoria is also endorphin-mediated. Forgive me for changing the subject, but have you ever considered the possible parallels between the effects of electrical and musical frequencies on the brain? Doesn’t Dr. Patterson use electrical frequencies that roughly coincide with the frequencies of various notes on the musical scale, and occasionally superimpose them to produce harmonic effects?

Pete: Who knows? Maybe, if Meg’s got enough years left in her, she’ll get a place at Juilliard and become incredibly rich and famous playing her little black box. In all seriousness, though, it’s interesting that you should bring that up, because Meg feels she was fortunate to have treated so many musicians in the early days, when she was still largely in the dark about what frequencies would work best. Apparently, the musicians would fiddle around with the machine until they found a setting that felt good. They seemed to know right away if the frequency was helping them. So the fact that musicians seemed to be more attuned to the effects of frequency aided her enormously in the refinement of the therapy.

Have you ever thought to gauge the human physiological response to music, with the goal of exploiting such knowledge in your own compositions?

Pete: In 1972 I wrote a story called “The Lifehouse,” which explored the Sufie notion that all life and all nature — especially anything expressed, received, or imparted — is based on harmony or dis-harmony of a very physical variety. In other words, if you are in harmony with the people around you, and in harmony with life, your body has become more attuned to certain rhythms and frequencies. And when you attain higher levels of spiritual equipoise through meditation, biofeed-back, or other methods, what you are really doing is exposing yourself to elevated and hopefully longer-lasting rhythms and frequencies of brainwaves, breathing, heartbeat, pulse rate, and so on.

While I was working on “The Lifehouse” script I actually did a lot of experiments with sounds that were produced from natural body rhythms. I was working with the musical bursar of Cambridge University at the time. What we did was ask some individuals a lot of questions about themselves and then subject them to the sort of test a G.P. might undertake. We measured their heartbeat and the alpha and beta rhythms of the brain; we even took down astrological details and other kinds of shit. Then we took all the data we’d collected on paper or charts and converted them into music, and the end result was sometimes quite amazing. In fact, one of the pulse-modulated frequencies we generated was eventually used as the background beat to “Won’t Get Fooled Again.” Later I used another one of these pulse-modulated frequencies as the foundation for “Baba O’Riley.” As a matter of fact, I used a similar technique again on the Who’s latest album, It’s Hard.

On which song?

Pete: It’s called “I’ve Known No War.” We used a series of rhythmically modulated frequencies. For instance, we’d start with two notes that had a certain amount of inter-harmonic distortion, which was basically fairly pure frequency-wise. Then we’d break the sound up rhythmically. You have to listen to it with very, very, very open ears — that’s the only way I can describe it. You listen to the music it creates in your head. It’s strange, but people are quite content to listen to a series of chords without needing melody, because the catalytic event occurs in their mind — that’s where the melody is created.

Perhaps a story from my childhood might help to illustrate my point. I was in the Sea Scouts-sort of the nautical equivalent of the Boy Scouts. One day, when I was about ten years old, we went out for a ride in a boat with an old, rusty outboard motor on the back. As we bobbed along in the water, the engine made these funny noises — brrrrrrrrrrrrr and browowrowowrowowrowowrowow. By the time we had gone up the river and back again, I had to be carried off. I was in a trance of ecstasy. When they turned the outboard motor off, I broke down — I actually physically broke down. At some point in the journey I had gone off into a trance. I began hearing the most incredible sounds — angelic choirs and celestial voices. What I heard was unbelievably beautiful. I’ve never heard music in my imagination like it since. But I’ve always realized the potential for sounds to ignite my imagination like that. To this day, I’m a bit scared to let a sound take me that far.

Earlier you suggested that spiritual equipoise is attained when the body’s internal rhythms are in harmony with the surroundings. Do you think true fulfillment could be achieved using a device — say, a more sophisticated black box — that would fine-tune our systems?

Pete: No, I think fulfillment is something that ultimately has to come from outside. The realization that “Yes, I’m on the right track spiritually” probably begins with the discovery of some small yet highly significant coincidence in the events happening around you. It begins with a feeling of euphoria, a feeling of being a channel for some form of love or positive energy that is beyond your limited capacity. You give more because you’re not expected to give; you’re fueled by an energy coming from the outside. The ability to give more and to actually influence events far beyond your immediate domain might even develop to the extent that when you say, “I prayed and my prayer was answered,” what you’re really saying is, “I prayed, and then I answered my prayer.” Part of the spiritual process is the realization that the highest goal one might ever aspire to is not that I’ll run a fifty-mile marathon; not that I’ll go on the stage and make 26,000 happy tomorrow; not that I’ll try to love my wife and children — but that I will love God. That is what produces the greatest human satisfaction and fulfillment in every individual of every religion in the world.

Everything you read about spiritual matters — things that were supposed to have been conveyed by God via messengers — is about the human being’s potential to attain universal, infinite consciousness. The human potential is that great. And when you aspire to that, you become oriented to a wider scope, whereupon you really do become a channel for powerful outside forces beyond your immediate control.

“I suppose that for about a month, maybe two months, before being treated, I’d felt no sexual feelings whatsoever. So the treatment definitely had a rekindling effect.”

Do you feel that power?

Pete: I think I have felt it in the past. In fact, part of the reason the low point in my life was just so staggering was because it followed a long period of feeling great spiritual strength. After soaring so high, I suddenly crashed. The most humiliating aspect was having to admit that I couldn’t deal with my full potential.

Do you feel better able to cope as a result of the treatment?

Pete: Yeah. You learn something about yourself and your own capabilities. I’ve come to view NET as an education in itself. It teaches the body to produce its own drugs, and in the process you become aware of the potential within you to deal with crises, tensions, and frustrations. It definitely reaffirms one’s faith in the self-healing process.

Yet you could view the black box as an electronic fix. It does, after all, produce a surge of opiates in the body.

Pete: Except that it smooths out the production of endorphins. In the beginning of the treatment, there may be jagged rises and falls in endorphin levels and your emotions fluctuate dramatically. But by the end of the ten-day therapy, your mood starts to stabilize as the endorphins are replenished to the appropriate level. There’s no rush. You just feel normal.

So you don’t fear a black market in black boxes?

Pete: To be perfectly honest, the few people I know who’ve undergone the treatment have all shared a hatred of the fucking box from the first moment that they saw it to the time when they happily ripped it off and chucked it away. You don’t develop any affection for the black box. Even though you know it’s rebuilding you, there’s no kind of “Ah, little black box!”

I should tell you a story, though I hope it won’t put you off NET. When I returned to England after being treated by Meg, I ran into this guy who had stopped using heroin under great duress by substituting Ativan in its place. When I started to tell him about NET his eyes lit up, and he became more and more excited. I thought I must really be giving this guy hope. He must be so relieved to know that there’s a cure that will get him off heroin forever. What joy this must be bringing him! You could see it in his face. He was getting happier and happier and happier. Finally, he could contain himself no longer. “It’s exactly what I thought!” he exclaimed. “We’ve got the most incredible drugs inside us — it’s just a question of unleashing them!”

I went off into the crowd in a daze. It was so incredible seeing it from his point of view. Phil the Pill we used to call him. A very sweet little man, twenty-three years old, eyes like saucers.

Why do you feel able to deal with all sorts of adversity when it was a little electronic gadget that saved you?

Pete: I know that the machine didn’t do it. I know I did it. What the machine did was train my body to do it. I understand that there were no drugs or anything else from the outside except stimulus. So I did it. I got off heroin, and Ativan and cocaine and everything else. And that’s made me complete.

We found it interesting — albeit not really that surprising — that NeuroElectric Therapy, which seemed ready for FDA approval back when this article first published in 1983, still awaits that amidst the typical debates over anything new in the health field. A cynical person might believe that giant pharmaceutical companies much prefer treatment to cure, y’know? In less controversial news, we can point to another interview more about The Who that we also reran here in Legacy, it from December, 1974 originally. Apparently the mid 70s had a lot of people who “can see for miles” working at Penthouse.