It’s rare for the world heavyweight boxing champion to dedicate a fight to another boxer, but it’s even rarer when that boxer is a prisoner.

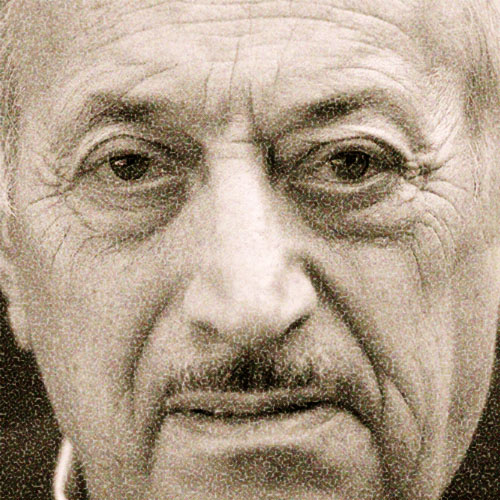

Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter

Yet that’s just what Muhammad Ali did on the May morning before his bout with Ron Lyle, when he told startled reporters in Las Vegas, “I’m dedicating this fight to Rubin Carter.”

I come to you in the only manner left open to me. I’ve tried the courts, exhausted my life’s earnings, and tortured my two loved ones with little grains and tidbits of hope that may never materialize. Now the only chance I have is in appealing directly to you, the people, and showing you the wrongs that have yet to be righted … the injustice that has been done to me. For the first time in my entire existence I’m saying that I need some help. Otherwise, there will be no tomorrow for me: no more freedom, no more injustice, no more State Prison; no more Mae Thelma, no more Theodora [wife and daughter], no more Rubin … no more Carter. Only the Hurricane.

“And after him, there is no more.”

— From “The Sixteenth Round” by Rubin Carter (Viking Press)

For those few boxing fans who hadn’t heard of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, or didn’t remember his furious devastation of opponents in the ring during Friday-night fights in the sixties, Ali’s decision to become co-chairman of the Hurricane Fund came as a surprising introduction to a man who has become a living symbol of courage and a cause celebre for fighters against injustice.

In 1966 Hurricane Carter was the number-one contender for the middle-weight crown. With twenty-one knock-outs under his belt and about to take on Dick Tiger for the title, Carter was near the peak of his career. And then, suddenly one night in June, shotgun bIasts in a dingy Paterson, New Jersey, tavern shattered his hopes forever. There would be no title bout — in fact, no more fights at all for Rubin Carter — just years wasted behind bars.

Rubin Carter, known to the Paterson police for his civil rights activities, was swept up in the dragnet thrown over his hometown that night after the murder of three white patrons of the Lafayette Bar & Grill. The police had already chased and lost a white car similar to the one driven by the murderers as they fled the city, and many other white cars driven by blacks were stopped and searched that night; but only one — Rubin Carter’s — was brought to the scene of the crime to confront the lynch-mob hysteria of white neighbors and witnesses. Even so, no one — either witnesses or the only surviving victim — identified Carter or his young companion in the car, John Artis, as the murderers. After seventeen hours of grilling by police and after Carter passed a lie-detector test, the two men were released.

Five months later, on October 14, 1966, Carter and Artis were arrested and charged with the murders. On the testimony of two white ex-convicts, Alfred Bello and Arthur Bradley, Carter and Artis were imprisoned, and in May 1967 they were brought to trial. there followed two weeks of courtroom drama packed with racial tension: black defendants confronted by white judge, a white prosecutor waving the blood-soaked clothes of the white victims, and an all-white jury chosen from a community informed by a racially inflamed local press. The result was that both defendants received triple-life sentences, with Carter’s set to run consecutively — or, in other words, forever.

But then, in September 197 4, the prosecution’s key witnesses, Bello and Bradley, recanted their testimony. They explained that they had lied in exchange for rewards of $10,500 offered by the police and promises of leniency for robbery charges. “There’s no doubt Carter was framed,” Bradley admitted to the New York Times.

So seven years have been cut out of Rubin Carter’s life. He has spent those years studying every law book he could lay his hands on, attempting to nurse the emotional wounds of his wife and daughter, struggling for prison reform at Rahway State Prison, and using his boxing ability to ward off attacks by sadistic guards and homosexual assailants. It seemed — at last — in the early fall of 1974 that this longest and most difficult fight of his life was nearly over. Using the recantations of Bello and Bradley, lawyers from the State Public Defender’s Office asked for a new trial in a hearing before Samuel Larner, the same judge who had originally sentenced Carter and Artis to life while expressing his full agreement with the jury’s verdict of guilty.

But Judge Larner denied Carter’s right to a new trial, allegedly to “preserve our jury system,” and Carter is now awaiting the outcome of an appeal that may take years before it even reaches the federal courts. Only there, beyond the power of the New Jersey political machine, Hurricane Carter told Penthouse interviewer Gerard Colby Zilg, does he expect any chance of “a fair shake.” Recently, in late May, Judge Larner refused to free Carter and Artis on bai I while they appeal. He described the bail application as “frivolous.”

Why has Rubin Carter been denied justice in New Jersey? The answers given here in this exclusive Penthouse interview reveal for the first time the politics behind Carter’s case. These include a two-year history (from 1964 to 1966) of constant harassment by the FBI and a nationwide pol ice campaign to “get” Carter because of his civil rights activities and his outspoken support of self-defense against police brutality. They also include Carter’s fight against the boxing establishment; his association with Martin Luther King and the Rev. C.L. Franklin; the role of New Jersey’s present governor, Brendan Byrne, in the original trial and imprisonment of Carter; and the real reason Judge Larner was able to turn down Carter’s appeal for a new trial.

To obtain this interview, Zilg traveled to Trenton State Prison, which he describes as “a decaying monument to 126 years of collective misery,” and talked with Carter for six hours. “He was smaller in size than his name had led me to expect,” Zilg says, “but Rubin Carter has a dynamism and strength of character that immediately fill any room. He sports the same Fu Manchu beard and shaven black head that intrigued me on TV years before, but the fierce image I had of him faded before the genuine warmth of his greeting and his broad, generous smile. The buoyancy in his step and his youthful optimism almost make you forget all that this thirty-eight-year-old man has been through. He speaks in a low cadence dramatized by gestures, and only the unseeing gray cloud of his right eye reveals the hidden pain behind the gold-framed glasses. His meticulous attire — clean khaki slacks, an immaculate white turtleneck shirt, and a black turban adorned with a pearl pin — clearly testifies to his determination to preserve identity and self-respect in the face of the conformity of prison life.”

For eight years you have been imprisoned for murder. What do you believe is the real reason you’re in jail?

Carter: I’m not in jail for committing murder. I’m in jail partly because I’m a black man in America, where the powers that be will only allow a black man to be an entertainer or a criminal. While I was free on the streets — with whatever limited freedom I had on the streets — as a prizefighter, I was characterized as an entertainer. As long as I stayed within that role, within that prizefighting ring, as long as that was my Mecca and I didn’t step out into the civic affairs of this country, I was acceptable. But when I didn’t want to see people brutalized any longer — and when I’d speak out against that brutality, no matter who committed the brutality, black people or white people — I was harassed for my beliefs.

I committed no crime; actually the crime was committed against me. All the evidence today shows that the crime was committed against me … and still is being committed against me. What has happened in the past and what’s happening right now make it a very good bet that it may happen to you tomorrow.

When did the harassment begin?

Carter: As far as I can recall, it began in January, February, and March of 1964. Before that time, I was the Rubin Carter that everybody loved, a good guy. Muhammad Ali and I once had to appear in front of the New York Boxing Commission up in Albany when some people were asking for the abolishment of boxing. Muhammad was the good guy who showed what boxing was doing for him. Then I was put on display as the former bad guy who had come out of prison, and I explained what boxing had done for me. I was the black American pie at that time.

But the moment that I got rid of my manager, Carmen Tedeschi, because he had beaten me out of all this money, then the news media came down on me. They started saying I had left the man who made me — even though each time the bell rang, he grabbed the stool and went and sat down outside the ring.

In other words, you were challenging the boxing establishment?

Carter: Yes. Before that, I would never say much. My manager would do all the talking. He was a publicity hound, and he would always bring up my past — that “my man was in prison” stuff. I let it go, and that, I believe now, was a mistake on my part. Because the moment I got rid of him and started speaking for myself, that’s when people started saying, “He’s challenging boxing.” From that time on, everybody really started coming down on me.

But my real problems began when the Saturday Evening Post printed what I said about the Harlem fruit riot that took place in April 1964. I said that black people ought to protect themselves against the invasions of white cops in black neighborhoods — cops who were beating little children down in the streets — and that black people ought to have died in the streets right there if it was necessary to protect their children. When a reporter — and a very good friend of mine, or so I thought — asked me about this Harlem fruit riot, I told him how I felt about it. None of this was supposed to be printed, but he saw a story in it and had it printed in the Saturday Evening Post. Well, when that came out the police throughout the world thought I had declared war on them … and when war is declared, truth is always the first casualty. It was at that point that police throughout the country came down on me. There were times when I was arrested three or four times just to put in the headline RUBIN CARTER AGAINST THE POLICE in the papers. This is a very skillful maneuver to turn the victim into the criminal and the criminals into the victims. Because not only did it alienate me from white people — the papers said I was a racist bent on killing all blue-eyed devils — but it made black people scared of me too. So I was isolated, hung out there. Meanwhile, I’m trying to fight, trying to go on with my career, and I’m catching pure hell from everybody.

Were you arrested outside of your hometown, Paterson?

Carter: Yes, in Hackensack, New Jersey. I was riding down the highway and my car broke down. I pushed it off the road and walked on down the highway hoping to find someone to help me get it fixed. So when this police car came up on the other side of the highway, I jumped over the viaduct and said, “Man, am I glad to see you. Would you take me to a service station?” He said, “Sure, come on with me, get in the car.” So I got in the car and he said, “Let’s stop by your car to see if we can start it.” He had jumper cables in the back. We pulled up to my car and on the side it had my name in silver letters, Rubin Hurricane Carter. Well, when we couldn’t start the car, he said, “I’ll take you down to a telephone booth.” But he took me straight to the pol ice station and got me in there with all his buddies. And he said, “You know who this is? This is Rubin Hurricane Carter,” and all of them pulled guns on me. Then they locked me up and charged me with breaking into a meat-packing place somewhere in the city. I stayed there about seven or eight hours, knowing that I was going to prison if I couldn’t get a message out to anybody. They wouldn’t let me make any telephone calls, but that morning a black police officer came into the station, saw me sitting in that cell, and he said, “What the hell are you doing here?” I explained to him and he was angry. He began cussing and finally nobody knew who put me in jail or anything, and they let me go. But that was the type of thing that I was running into constantly.

When you were in Los Angeles for a fight, you were required to report to the L.A. Police Department. You wrote in your book that the police chief, William Parker, told you that the FBI had kept close tabs on you. What about other examples of harassment by the FBI or other federal agents?

Carter: I had a few friends who were Secret Service men and federal marshals, and they told me about the file they had on me. They were following me around. Each state that I went in to fight, the moment I got into town the police rode down on me, fingerprinted me and mugged me, and I would have to carry this card attesting to the fact that I was an ex-convict. The harassment was steady … constant.

When you arrived in various towns, did the authorities come and get you?

Carter: Yes. They knew I was coming, and someone had to contact them that I was coming.

Do you believe the FBI has a file on you?

Carter: Absolutely. There is no doubt about it. I remember when I was in Los Angeles and got off the plane that day, I saw this beautiful woman … I just happened to look at her and then kept on going. But in the air terminal I saw the woman again. She was always behind me. And when I got to the motel on Olympic Boulevard in L.A., she was at the motel. I didn’t connect it with anything, but I kept seeing this same woman. And then, when Chief Parker called me up at the motel and told me I’d better come down to the police station to register as an ex-convict, there she was — trying to hide in his office. That’s when he told me that the FBI had been following me every step that I had taken in Los Angeles.

You participated in Martin Luther King’s march on Washington in 1963. Yet in 1965, when Reverend King asked you to participate in the march in Selma, Alabama, you didn’t. Why was that?

Carter: Because of threats on my life. I was catching pure hell in the North and the West and all the other places I was going, and I knew that if I ever went to Alabama nobody was going to protect me down there. Dr. King was talking about nonviolence, about being peaceful — laying down on the street while police dogs were biting you and horses were stomping on you and cops were beating you over the head. Well, I knew that I could never be nonviolent. I’m a peaceful man, but that doesn’t mean I’m nonviolent. If you will be nonviolent with me, then I will be nonviolent with you. But if you are going to put some violence on me, I’m going to whip it right back on you.

In your book, you described a “plan of black mass murder.” Would you explain this for us?

Carter: Each time a civil rights bill was passed, black people died in the streets. In 1964 the civil rights act was passed, and a few days after that you had the Harlem fruit riot. And then riots were proliferating un-checked all over the country. Later, you had the voting rights act signed, and then Watts came up. Every time somebody would say that some kind of rights were going to be legislated for black people in this country, the racist elements in the political system and the police would immediately bear down on black people and show them that even though these rights were signed into law, they didn’t recognize that law.

Do you believe that agents provocateurs were involved?

Carter: Well, I really didn’t know then. But, yes, I believe it now.

With your beliefs about self-defense, how did you handle all that harassment from the police and FBI?

Carter: I had to hire an adviser to handle the police. This adviser went with me everywhere, but I stayed out of the country and up in my training camp so much that he got tired. He was married and had children, and his wife got tired of him staying away nine months out of the year. So ultimately he left me too.

They were isolating me. And this was before black people were proud to be black, you know. There was no “Black Power” then, so I was hung out there by myself, and people would say, “Well, that crazy nigger is in the papers again — messing with some cops again.” I was seen as messing with all the police forces in the country. During all that time I had to go to other countries to fight because the cops were really coming down hard on me at home.

So you were actually forced into exile in a sense?

Carter: Yes. I had to go to Africa to fight. I had to go to London, to Paris, to South America — just to stay away from here. It was brutalizing me, mentally, because in fighting if you aren’t in shape, both mentally and physically, you’re no good.

What were the circumstances of your arrest for the Lafayette Bar & Grill murders?

Carter: It was about one o’clock in the morning and I was riding down the street — I’m a night man, you know. When you train in the day, you sleep all night; and when you come out of training, your body clock gets all messed up. So I was riding down the street one night. … Now, just that afternoon I had seen in the papers that they had police on rooftops allegedly guarding some witness to these murders (that was Bello, I found out later), and everybody knew it — so if I had committed that crime I would have been long gone. Well, that night I went to turn a corner, and the next thing I knew there must have been 20,000 police shotguns in my face. Just that quick. Wow! “Keep your hands on the wheel,” someone said, so I kept my hands on the wheel until they hand-cuffed me behind my back and put me in a car.

Now, the police station was only a block away, but they didn’t take me there. They took me up into the Paterson mountains — about ten cars of detectives, all with unmarked cars. And I was sitting handcuffed in the back — with two detectives up front and two detectives in the back. They took me up into those mountains, and they parked. Nobody said anything to me. We just sat there. I could hear these loudspeakers … these microphones, going back and forth, chattering angrily … very angrily. You could see policemen walking around out there with shotguns. No light anywhere, just a dark road. And I thought, “My God, these people are going to kill me!” We stayed there about an hour-just sitting there, nobody saying anything to me. Then, all of a sudden somebody on the car radio said, “Okay, bring him in.” It seemed like they were very disappointed, as if somebody had talked them out of killing me — that there would be a big investigation or something if they killed me — which wouldn’t have meant shit to me. I would’ve been dead!

After you were picked up on the night of the murder, and none of the witnesses were able to identify you and John Artis, you took a lie-detector test that proved your innocence. Why wasn’t that used as evidence in your trial?

Carter: At that time, in 1966, the lie-detector test wasn’t admissible in court.

Weren’t there other white cars that were stopped by the police?

Carter: Yes. In the court records cops said, “I stopped this car here, I stopped this car there,” but mine was the only car that they stopped and brought to the scene of the crime.

During the trial, were any of the defense witnesses threatened?

Carter: Yes. My God, yes!

Who were they? Can you give us any specific names?

Carter: John “Bucks” Royster. He was the third person in the car with me on the murder night when the police stopped us.

He was threatened? By whom?

Carter: By the police.

And who else?

Carter: My sparring partner, Wild Bill Hardney. He was run out of town. He lived in Newark at the time; and when the Paterson police knew that he was coming as a witness, they got in touch with the Newark police and the Newark police ran him out of town.

Is it true that of 400 potential jurors, only eight were black? And that the only selected juror who was black — a West Indian — was the only one dismissed?

Carter: Yes, that’s right. Ain’t that something? You know, those are astronomical odds — that out of fourteen people on the jury the only black man would be taken off!

With the recantations of the prosecution’s key witnesses, Bello and Bradley, and all the other facts that have come to light about the suppression of evidence by the police — for instance, discrepancies concerning the time the police turned in the bullet they claimed to have found in your car — and with so much more new evidence crying for a new trial, why do you think Judge Larner turned down your appeal?

Carter: Well, of course, Judge Larner turned down the appeal because he secured the conviction — and Larner wasn’t even a judge before he tried my case.

You mean that was his first case as a judge?

Carter: That was his first and he wasn’t even from the same county I was. You see, in 1966 I was the number-one middleweight contender and an international figure, and everybody in Passaic County — well, everybody in New Jersey — knew that this was a frame-up. None of the judges in Passaic County would touch this case because they knew it was a farce. But they still had to try me, so the governor of New Jersey at that time, Hughes, appointed Larner, at that time a lawyer from Essex County, on September 21, 1966 to go into Passaic County and try my case as his first criminal trial. Now Hughes did this for various reasons, but specially because he knew that Raymond Brown was my attorney. Well, Brown was the best criminal lawyer in the state and a black man. And Larner and Ray Brown were bitter enemies-they had been in cases together before. So they sent Larner in there to hold Brown down and get me convicted. Larner acted like a prosecutor from the bench, and the moment he got me convicted they shipped him back to Essex County. They put him into civil law because he didn’t have enough criminal trial experience.

You mean they let him try your case, then they said he didn’t have enough experience and sent him back to civil court?

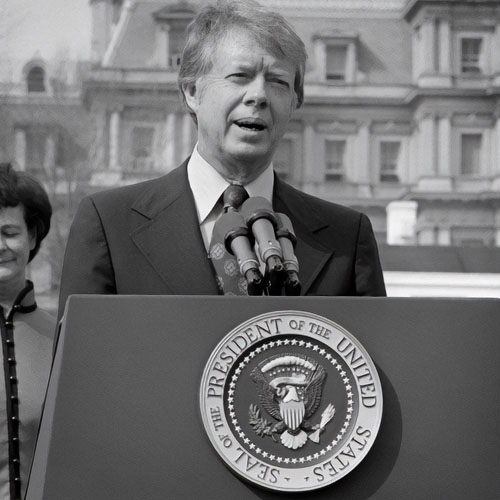

Carter: Yes, civil court in another county. So therein lie our political implications: Hughes, who was governor of the state of New Jersey at the time and who is now the chief justice of the State Supreme Court. We also have Brendan Byrne, who is the governor of New Jersey right now; he was in cahoots with Larner at that time. When these two criminals testified for the state in 1966, they had nine or ten armed robberies throughout New Jersey to answer for. Well, Brendan Byrne, who was then the Essex County prosecutor, went around to all the judges in his county and had them quash al I those indictments because they testified against me. So there you see the political ramifications.

Larner was from the same county as Byrne?

Carter: Yes. So when you ask why did Larner deny that appeal, well, he’s the guardian of that conviction. He said right from the start of the hearing, “Why should the State be deprived of this conviction?” Those were his exact words — not why two human beings should be deprived of their lives because of vicious and prefabricated lies:

Because I will not say that I’m guilty, or act like I’m guilty, I am a threat to the administration, to the politicians. You know, there are brutal people in control of these prisons. There is no accountability all the way up the ladder. We are just left here with these people, and they are vicious. There have been several instances in the last four or five months of people being brutalized to death right here in Trenton State Prison. This is the snake pit of the politicians. This is the place where they kill you, and that’s why they moved me here after the Rahway rebellion. I have as many problems with the inmates as

I do with the guards and the administration. I’m like a man sitting on a high fence at noon. This place is very dangerous for me, from both sides of the fence. If for a moment either the administration or the inmates here felt as though Rubin Carter was weakening in his fight to any degree, they would pounce on me and wipe me out. It’s very dangerous for me here.

I’m blind in one eye because of a lack of proper medical attention in this Trenton State Prison, and I know that if I get sick — in here I’m going to die. I know that because it’s what the administration wants. They showed me that very clearly when they blinded me in my eye.

What did happen to your eye?

Carter: I don’t know. When I came into this jail, I had perfect vision — no problems ever with my eyes even when I was a prize-fighter going through all that rugged stuff. I never had problems with my eyes. But then I came to this jail, and when I was here about three weeks I had an examination — at that time they gave every person an examination; now they don’t give you anything — and the man who gave me the examination said I had a detached retina and that if he didn’t reattach it, I would slowly lose my sight in my right eye.

The doctor who operated wanted to take me out to his hospital — St. Francis Hospital here in Trenton, where other prisoners go for major operations — but the administration wouldn’t allow me to go. Everybody else could go but not Rubin Carter. They made that doctor bring his tools and his nurses into this slaughterhouse here and operate on me in this butcher shop. After the operation he prescribed different medications that I should take to help heal this eye. But the prison wouldn’t give them to me.

You were denied your medication?

Carter: I was denied my medication, and therefore I ultimately went blind in that eye.

Every month after that I used to go to the eye doctor to have him examine my eye to make sure that my bad eye could never damage my good eye — because all I had now was one eye. When I went to this doctor in February 1974 he looked in my eye and jumped back, flabbergasted. “My God,” he said, “you’ve got stitches in your eye!” All these years my eye used to secrete a lot of mucus, and every time I’d go to sleep and wake up in the morning I’d have to pry my eye open. I thought it was mucus escaping from my eye, but actually it was stitches that they had neglected to take out after seven years.

Right away, I wrote my lawyer. Then the prison administration told me that they were going to take me out to the hospital at Rahway to remove the sutures. They wanted to get me out of the prison quick to get rid of that evidence. So I said, “No, I’m not going for that.” But all I really wanted was to be able to see, so when they said they’d reattach my retina, I said okay.

I went to New York’s Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, and they took me into the operating room, put me under as if they were going to reattach my retina, removed the sutures, and then sent me back. They didn’t even attempt to reattach my retina.

At that point, I saw that if something isn’t done here about the constant lack of medical attention, the brutality, the maiming and mutilating of people — then everybody’s going to die.

Some years back you befriended an elderly prisoner by the name of Summers. He was being bullied by some inmates and you defended him in a fight. That same night he committed suicide. Your book gives the impression you were greatly affected by his death. What did you learn from that experience?

Carter: There were many things. Mr. Summers was a great intuitive man who had really lived his experiences. But the very things that were happening to Mr. Summers at that time are the same things that are happening now — frustration, falling into a deep pit of depression. And there’s no help for you, so you say, “I can’t do it anymore.” The other day the very same thing happened. A young boy, nineteen years old, was hanged. You never hear about these things. He hanged himself in that place for “incorrigibles,” the Vroom Building … in fact, he hanged himself the same day the “Mike Douglas Show” came here to tape me in the death house. The guards had told Mike Douglas, “No, nobody’s been killed here in seven years,” and this man had just been killed that morning. Lies, you see.

The boy hanged himself?

Carter: He allegedly hanged himself — put it that way. Because nobody ever knows. But the depressions are real, you know. You see guys staying in cells all day or all night long, and they don’t get any mail from their families. And they’re facing 100,000 years with no hopes of any kind. When you break hope in a man, that man is dead. The average age in this prison is about twenty-three years, and the majority of them are doing 100,000 years. But they come here and they want to finger pop. You can get all the dope you want in this jail — so they stick dope in their arms, drink whiskey, and try all kinds of other foolishness, just to try to escape. But when they wake up in the morning, they’re still here. Later, when they go out into the streets and have to rise or fall on their own merit, they find themselves totally at a loss. Some are physically fit but mentally destroyed. They find it easier to remain shadows in jail than to live as responsible human beings on the street. That is the crowning achievement of all these prisons.

The administration knows all this is going on?

Carter: Sure.

Does the prison administration consciously encourage homosexuality?

Carter: Oh, yes. Anything that would strip a man of his manhood — of any type or form of masculinity. It has only been recently here, about two years I would say, that they allowed men to wear mustaches and beards.

Guys come into jail and they live under this painful passivity for years, they live with the brutality, they live with being killed constantly. And when they walk out of this prison they are very dangerous people. I see guys come in here with a two- to three-year sentence for breaking and entering, and when they walk out that door I know they are going to kill somebody.

Everyone knows what is happening in this prison. Everyone knows where all the dope is coming in at who is bringing it in. Everyone knows who are the police bringing the knives in. You know that. But this administration — in order to keep the war going on paper, in order to keep the taxes rising, in order to milk the public out of more money — says the prisoners’ families are bringing it in — my wife is bringing it in, my daughter is bringing it in.

Aren’t there any investigations into this activity?

Carter: Yes. From the time that I arrived at Trenton State Prison in September of last year, there have been no less than ten suits filed in federal courts about the brutality that is going on here. A newspaper reporter named John Toff from the Trentonian, a newspaper here in Trenton, worked undercover in this prison as a guard for about seven months. Then he quit and wrote a series of articles exposing all of the brutalities that were taking place and all of the guards who were deliberately committing them. But his paper is just a tiny paper, and it doesn’t go any further than Trenton. So no other communities in New Jersey know about this exposure or anything else. If it had been a national paper, it would have torn this place down.

Yes, there are suits and investigations going on here. But the administration is investigating itself. The politicians that control these prisons are investigating themselves. And you know that nothing is ever going to come out of that. There is no accountability here — just exactly like there’s no accountability in the street where you are. And we know that accountability is the cornerstone of any democracy. We have no accountability here, and you have no accountability out there, so we have no democracy. We’re all living under false pretenses.

During the Rahway rebellion, you stated in your book that, “if there was some kind of list being passed around of whom to get, of the inmates who were definitely slated for the graveyard, as there had been in other riots in New Jersey, I knew that my name would be at the very top.” Do you still believe that?

Carter: Absolutely! It is still so, right here in this prison. In the whole state of New Jersey, Rubin Carter’s name is at the top. So if anything happens here, they are going to kill me — and they will be justified in the public mind, because all they have to say is, “He is here for murder.” That’s all they have to do. It’s like the time they came down on me at Rahway at twelve o’clock midnight with shotguns and machine guns and movie cameras. They brought those movie cameras there just to show that if I had balked for a second, they would have shot me down and said, “See, this is why we shot him down, because he is a murderer.” And people would have believed that.

You have studied law while in prison. Based on this, what would you have done differently in handling your defense? For example, at your first hearing for a new trial, what did you actually ask your former lawyers from the State Public Defender’s Office to do that they refused to do?

Carter: I asked them to bring in Governor Byrne and the five judges in five different counties who sentenced Bello and Bradley for those other crimes. I wanted to bring in the five prosecutors of these counties because we have evidence — hard evidence — that letters had been sent out by the Passaic County prosecutor to the prosecutors of those five counties saying, “Go to court for Bello and Bradley because they got Rubin Carter.”

Was one of those Brendan Byrne?

Carter: One of those was Byrne, and Byrne did go. We have evidence that says that Byrne went, and we have transcripts in which Judge Camarado from Essex County says, “The prosecutor called me up this morning, Prosecutor Byrne, and told me to dispense with this case.”

Now, at the hearing, Judge Larner had to decide whether to believe Bello and Bradley, as opposed to the prosecutor. Naturally he was going to believe the prosecutor. So I told the lawyers, “If you bring in Governor Byrne, if you bring in the five judges, if you bring in the five prosecutors, then who is Larner going to believe in terms of credibility? Is he going to believe the governor, the five judges, the five prosecutors, or is he going to believe this prosecutor over there? Make him make a decision — make him make a determination on the credibility of the governor.”

But these lawyers [from the State Public Defender’s Office] had entered into a stipulation, without either my knowledge or consent, that they would not call in my witnesses — the governor, the five judges, or the five prosecutors.

Who did they make that deal with?

Carter: With Larner and the Passaic County prosecutor. Now I know about stipulations, so when I found out I told them, “I want you to go back to the court and tell Larner I want that stipulation withdrawn immediately.”

Was that stipulation removed?

Carter: No.

Judge Larner refused to remove the stipulation?

Carter: Yes. So they did not put Fred Hogan on the stand — Hogan was their man who had investigated this case. They did not put Selwyn Raab [of the New York Times] on the stand. They did not put Hal Levitson [of WNEW-TV] on the stand. All those men had made independent investigations of this case. They did not put anybody else on the stand — just Bello and Bradley. Just so the judge would only have Bello and Bradley’s credibility to deal with. They made it easy for him.

When your appeal was denied by the New Jersey supreme court you said that you were thinking that maybe you shouldn’t see your wife and child again. Why was that?

Carter: Yes, and I still think that way. First of all, the moment that they put me in jail my wife and daughter were cut off from their livelihood. A prizefighter doesn’t have much credit. Whatever money you make you have to save, because there are no unemployment benefits or other Social Security benefits to fall back on. Also, I know my wife is young and beautiful and she has human needs. I felt that by my staying in jail I was limiting her life. My wife and daughter come here month in and month out, year in and year out-just to see me grow old and wither away on the vine.

Now that your case is beyond Judge Larner, do you think there’s a better chance for a retrial?

Carter: No, because the case is still sitting right here in New Jersey. The New Jersey judicial system is part and parcel of the thinking of Larner. I don’t believe that I will ever get a fair shake in New Jersey-unless the people demand it. The case must go to higher courts and ultimately to the federal circuit in Philadelphia, and then I think I might get a fair shot. But that will probably take years.

What can people outside do for your case?

Carter: Well, if the people aren’t from New Jersey, the political system here in this state isn’t going to worry — unless everybody gets together and says, “We demand justice — not because of Rubin Carter but because there is a right and a wrong here.”

Open the books — let us all see them. If people would say that about this case too, they would have to do it, and that is all I want. I don’t want them to just let me out free and pat me on the back. No, I don’t want that. I want to prove that I am not guilty.

What has Governor Byrne’s attitude been so far towards a new trial?

Carter: When this case was first publicized a year ago, there were several articles in the papers, and one quoted Governor Byrne. Someone asked him why he wouldn’t appoint an investigative body to look into Passaic County. And he said, “Well, nobody ever got a retrial or a new trial in New Jersey on recanted testimony.” And that’s true, because that’s what the law is in New Jersey; nobody has ever got it because all the recanted testimony in New Jersey has always been codefendants recanting on other co-defendants.

But this case is vastly different. First of all, Bello and Bradley were state witnesses, not codefendants. I had never seen Bello or Bradley in my life, other than when they brought me to trial. And they had never seen me before, other than when the police brought me to the scene of the crime on the night of the murders. On that night, they told the police that they could not recognize the people even if they had seen them. From the night of the crime up until five months afterwards, the police kept Bello and Bradley locked away in protective custody, grilling them and coercing them, and promising them rewards and leniency on their armed robbery charges — until finally they said, “Okay, it was Rubin Carter and John Artis.”

So what we have now are not recanted statements. What they are doing today is actually going back to their original statements.

Does Byrne know this?

Carter: Of course Byrne knows this! His pet phrase is, “It’s in the courts; let the courts decide it.” But the courts take years.

Recantation was the very thing that exposed Watergate. Recantation and plea bargaining. That was the only thing that uncovered Watergate — so you see exactly what recantations and plea bargaining really are. First, each of those people, Magruder and all the rest of them, said, “No, we didn’t do that,” but then they started saying, “Yes, we did do it.” That is a recanted statement. And all the federal judges — Sirica and all the rest of them — believed the recanted statements. So why can’t they believe the recanted statements here? What’s good for the goose is good for the gander. And that’s all I ask. I ask for a new trial. I never had a trial, because all I had was a kangaroo court, with none of my peers on the jury, with a misinformed, all-white jury that was in the heat of passion at the time. I just want a trial that is free from perjured testimony and manufactured evidence. That’s all. Give me a trial and I’m willing to accept that. I don’t want anything else.

Because you must be curious, we will give away the ending a bit here and tell you that Rubin Carter finally got out of prison on February 15, 1985 — after spending almost 19 years in prison. You can read a fairly short life story should you wish. Whether you do or not, it was horrible what happend to Rubin. Perhaps equally sadly, we say this at a time when the United States government works daily to try and whitewash (choice of word quite intentional) our racist history because apparently it makes some people feel bad to hear about it. … Now imagine living it.