“Take the headline ‘Baby Nailed to Wall.’ You say, ‘I never did that to my kids, although I had the impulse a couple of times.’ That’s where the horror is born.”

Stephen King … The Penthouse Interview

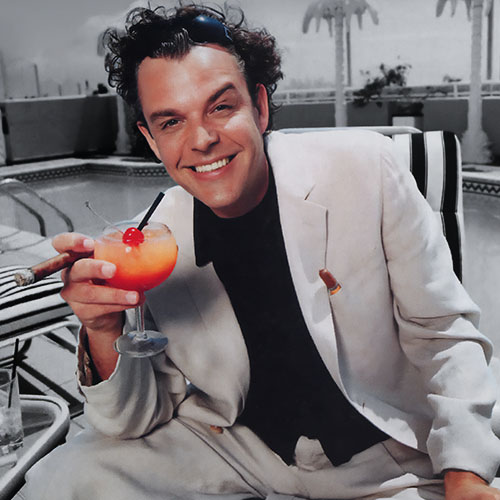

Stephen King sat anchored to the chair, picking at the green slime that hung from his jowls like Spanish moss, and stared at the test pattern on TV. Ever since the meteorite had fallen in his yard, the inevitable shone in his brain-damaged eyes and his body convulsed in concert with the wind. According to the script, Jordy Verrill had another few minutes to live, at best; then he could get on with the real business at hand: writing. For now, he played the death scene for all it was worth. On cue, Jordy lunged for the phone — his only hope — and missed. As he lay on the floor, doused in a sweaty concoction of fear and Ripple, the meteorite’s mordant glow transformed Jordy’s living room into a vast, godless tomb.

“That’s great, just great!” says George Romero, the renegade writer-director, who, since making Night of the Living Dead in Pittsburgh, has become anathema to the core of Hollywood selectmen allowed behind the camera. This time around, he’s directing the aptly titled Creepshow, a quartet of cartoon like horror tales, whose creator now lay in a twisted heap on the floor. “But … let’s do it once more. For posterity.”

“My posterity is killing me,” moaned Stephen King as he climbed gingerly to his knees. This was the third take in a series of difficult shots, and his King-size bones were beginning to wear around the joints.

Even at half-mast, Stephen King’s frame looms like one of his ghoulish fictional creatures about to emerge from a swamp. His size — he’s six feet four inches — and the sheer creepiness of his golf ball eyes create the impression that another mortal is about to fall victim in his shadow. It’s an effect he wears with good humor. “A few contortions — that’s all it takes,” he explains kiddingly, screwing his face into a diabolical pose. “I’m a natural. When I came up with the idea for this story, George knew I was the only one for the part. I mean, look at these eyes, man.” He glares into space. “There’s no fucking makeup on ’em!”

King’s presence is a convincing argument to sleep with a nightlight and shotgun nearby. He seems able to create his own eerie environment at will. Earlier in the day, sunshine had bathed the portals of Pittsburgh’s hilly terrain. Now, as King lumbered toward his trailer between takes, bolts of lightning slashed at the deserted Catholic school that doubles as a movie set as though God knew what was going on inside. “This weather’s the most comforting tonic for my soul. It’s the only sure sign I get that there’s madness in the air.”

Madness, of course, is Stephen King’s stock-in-trade. In less than ten years he has written nine books that have sold in excess of 35 million copies, clearly establishing him as the nation’s uncontested Master of Horror. With the publication of his first novel, Carrie (1974, which was made into the critically successful Brian De Palma film), King has left a trail of storied corpses strewn along the best-seller lists. Salem’s Lot (1975), The Shining (1976, and adapted for the screen by Stanley Kubrick), and The Stand ( 1978) carried him initially into the mainstream of popular fiction. King signed a controversial $2.5-million deal with New American Library in 1978, insuring his status at the bank, and since then has answered skeptics with a trio of consecutive number-one hits: Dead Zone (1979), Firestarter (1980), and Cujo (1981). A nonfiction contender, Danse Macabre, and a collection of short stories, Night Shift, fared less well, but King’s title remains firmly rooted in the public trust. With the exception of Alfred Hitchcock, no other modern horror master has made a stronger impact on the American public.

The success of his work, both critically and on the balance sheets, has left King with an unbridled sense of confidence. He dislikes “failed writers who take out their frustrations as ‘high-brow critics’” and also those people who turn up their noses at popular fiction. “Religion,” he says, “scares me more than anything I could possibly dream up.” And while he considers himself “brainwashed by a pack of dangerous Rock River Republicans,” King remains shamelessly conservative in his views on abortion, gun control, and capital punishment. As he languished in his trailer-whose starkness seemed populated by the ghosts of Jack Torrence, Andy McGee, or even Carrie White — Stephen King spoke candidly with Penthouse Contributing Editor Bob Spitz about some of the grim realities that enabled him to turn horror into the national pastime.

Considering your reputation as the number-one purveyor of horror fiction, how do you feel when you glance at newspaper headlines like “Baby Frozen in Refrigerator” or “Mom Nails Kid to Door”?

King: Love it, love it! Listen, I can say, “No, I hate that shit, I hate those papers” — and part of me does. But tabloids appeal to everything that is just sleazy in my nature. There must be a lot of it, too, ’cause, man, I open that paper and something jumps out at me on every fucking page. The headlines! Jesus! I mean, “Nun Raped in Brooklyn” and “Mob Puts Out Contract on Killer.” Tabloids have gone directly to whatever it is in people that needs to go to the worst things in life.

Do you think there’s a dark side in our personalities that relates to that kind of horror?

King: Take the headline “Baby Nailed to Wall.” You say, “I never did that to my kids, although I had the impulse a couple of times.” And that’s where the horror is born. Not in the fact that somebody nailed a baby to the wall, but that you can remember times when you felt like knocking your kid’s head right off his shoulders because he wouldn’t shut up. The Shining came from my own really aggressive impulses towards my kids. It’s a very sorry thing to discover, as a father, that it is possible, for bursts of time, to literally hate your kids and feel that you could kill them. And that’s where, on one level, tabloids help us say, “Thank God it isn’t me.” They’re helping people explore the dark limits of human behavior.

Is there anywhere you draw the line about how graphic violent horror should be?

King: Anything that you can see on the street, at any time, should be in a book. If the situation comes up, you point the reader right at it. That is to say, you shouldn’t walk away.

Even if it means leaving too profound an effect on impressionable minds?

King: In 1957 Arthur Penn made a film called The Left-Handed Gun, with Paul Newman. And in that movie Billy the Kid shot a guy who flew backwards right out of his boots, and you’re left with this image of the Western street with one cowboy boot standing there. People started saying, “This is gratuitous violence, this is too much.” Whenever anyone says “gratuitous violence,” what they mean is that someone showed us what it was really like, what those foot-pounds mean when they translate out of a fucking physics book and into the real world.

For years, in Western movies, someone would get shot with a forty-four, and the gun would go barn, and the guy would fall down. Kids went off to World War Two who, son of a bitch, thought that was going to happen to them if they got shot. They didn’t know that maybe they could get one of their balls shot off or get shot in the guts and never eat anything but poached eggs again. So if you’re going to do it, tell the truth, because otherwise you’re telling a very dangerous lie.

Even so, you’ve drawn stiff criticism for the irreverent portrayals of violence in your books.

King: A lot of critics see blood and say we’re turning the country into a bunch of mongrel dogs that are running for blood. What a pile of bullshit that is! As a matter of fact, when you shoot yourself in the mouth, blood and brains and hair splatter all over the place. If that’s going to happen, I want to see it. I’m going to wince, it’s not going to make me feel good, but I want to see what’s there.

Then how do you answer those people who claim that violence begets violence?

King: You show me the person who says, “King, that stuff you write is just full of gratuitous violence, you’re pandering to people’s lower tastes, you’ve got a tabloid mind,” and I’ll show you someone who doesn’t wear a seat belt in their car, because they don’t want to think about their fucking teeth going down their throat and aspirating into their lungs. They’re the people who, sooner or later, will be like Ronald Reagan; they’re going to push that button because they have no conception of what they’re doing or that it can really be the end.

“When you shoot yourself in the mouth, blood and brains and hair splatter all over the place. If that’s going to happen, I want to see it.”

Is “the end” — oblivion — something you’ve personally come to terms with?

King: I think that this idea about the end of the world is very liberating. It was for me, and I think most people feel the same way. It’s the end of all the shit, and you don’t have to be afraid anymore, because the worst has already happened.

That makes horror an escape mechanism to sublimate our primal fear.

King: I think that’s very true.

Then why does this generation seem obsessed with terrifying itself?

King: We’re the first generation to have grown up completely in the shadow of the atomic bomb. It seems to me that we are the first generation forced to live almost entirely without romance and forced to find some kind of supernatural outlet for the romantic impulses that are in all of us. This is really sad in a way. Everybody goes out to horror movies, reads horror novels — and it’s almost as though we’re trying to preview the end.

You’re saying our ultimate attraction to horror stems from a creeping paranoia?

King: I think we are more paranoid, but I don’t think that’s necessarily an outgrowth of the bomb. I think we have a pretty good reason to be paranoid because of the information flow. More information washes over us than washed over any other generation in history — except for the generation we’re raising. In college I became aware that a lot of people are paranoid, and I used to think: “Jesus Christ — they’re all crazy!” And then the thing about Nixon came out; the man was making tapes in his goddamned office. We find out that Agnew was apparently taking bribes right in the vice-presidential mansion — money being passed across the desk. Jimmy Hoffa is inhabiting a bridge pylon somewhere in New Jersey. And then you say, “Well, we really do need to be paranoid.” This flow of information — it makes you very nervous about everything.

Is there a fine line where horror and reality become indistinguishable?

King: Yes. It’s when I’m sitting there with the TV on, reading a book or putting something together, and this voice will say, “We interrupt this program to bring you a special bulletin from CBS News.” My pulse rate immediately doubles or triples. Whatever I’m doing is completely forgotten, and I wait to see if Walter Cronkite is going to come on and say, “Well, Dewline reports nuclear ICBMs over the North Pole. Put your head between your legs and kiss your ass good-bye.”

Isn’t that carrying it to extremes?

King: Yes, it is. But, even so, you think of the times that didn’t happen, when you got some other piece of news: when that bulletin came on that Robert Kennedy had been killed in Los Angeles, Martin Luther King had been assassinated, the president shot in Dallas. It changed everything.

So there is a very fine line where horror and reality cross.

King: Sure there is. And one of the reasons I think I’ve had some problems with Cujo is because people get a little bit worried when they read a book about this woman and kid trapped in a car by a Saint Bernard, and they say, “This could really happen.” Then they write me a letter that says, “Gee, I liked your vampire novel [Salem’s Lot] better, I liked The Shining better, because we know in our hearts that there are no vampires, and we are sure in our hearts that there are no hotels haunted by ghosts that come to life. But a Saint Bernard with a woman and boy in the car, that’s something else.”

It’s almost too realistic a horror to endure, the quintessential nightmare. Is that something you’ve had problems with in the past?

King: The review in the New York Times about The Stand was very downbeat. The [reviewer] didn’t like the book at all; he called it Rosemary’s Baby Goes to the Devil and slammed it off in five paragraphs. One of the things he said was that too many people pee in their pants in this book. Well, when something happens to someone that’s really scary and is very startling — that kind of “boo,” but it’s not “boo,” it’s something genuinely frightening — most people piss in their pants. I’m sorry if that becomes tiresome after a while. That doesn’t change the fact that it happens.

Don’t we get enough of that kind of horror on the six o’clock news?

King: I think the reason we do, and that this stuff is popular and successful, is because we get too much of it. If there is a utilitarian purpose, it’s to understand an essentially irrational act. With a lot of horror fiction, it’s an effort to observe irrational acts, or terrifying actions, or just to experience that feeling of being out of control.

To be totally out of control is what the best horror movies, in particular, can do to you. And that doesn’t imply any conscious flow — to say, “Oh, well, I’m going to see Friday the 13th because I’ll understand what happened to Sadat” — because it wouldn’t work on that level. But on a subconscious level, or even a psychic level, you may be able to say, “Well, here’s what I was feeling when I heard that Sadat was shot” — that same kind of helpless revulsion, terror, whatever it is. It’s on the screen, and it’s controllable — and it’s not real. It’s an effort to get around those feelings; sometimes it’s an effort to want them, and to say, “I can let you out. You can’t hurt me.”

Considering the influence that works of art wield over the public, are there any people who shouldn’t read your books?

King: I don’t think so.

No one ever borrowed a plot point or two to play out their own fantasy?

King: Well … there’s this thing that happened in Boston, where the police and papers called [the murderer] the Carrie Killer. He killed his mother — stuck her to the door with all these kitchen instruments. Obviously he had gotten the idea from Brian De Palma’s film; the kitchen implements weren’t in my book. But sooner or later there may come a time when some guy will do something and say, “I got the idea from a Stephen King novel.” I could say that people like that shouldn’t read my books. But if they didn’t get an idea from something that I wrote, they would get it from something somebody else wrote.

So there’s a chance that terror could, indeed, have a negative influence on someone teetering on the edge.

King: If he hadn’t been the Carrie Killer, he might have stabbed her to death in the shower and then he would have been the Psycho Killer.

What about the kid who blamed The Catcher in the Rye for driving him to murder John Lennon?

King: Same thing there. But I don’t feel any responsibility for the nuts and dingdongs of the world any more than any of us can live our lives on the basis of what some crazy person might do. For instance, I can get a bodyguard to walk around with me everywhere — which is not to say that at an autographing session someday, someone might not decide that I’m doing the devil’s work and shoot me in the head. We all live with that possibility; that’s a part of life.

Do you think people should be allowed to get away with blaming their violent acts on what they read or see?

King: No, I don’t. But the classic case of this is when the kids burned a woman to death with gasoline and then said, “Well, we got the idea from the ABC ‘Movie of the Week’” — which was Fuzz. It really put the kibosh on TV violence. It was the end of all those series like Peter Gunn and The Untouchables. But it’s still really killing the messenger for the message. If you are telling the truth, then it seems to me that if somebody — some nut — does something based on what you wrote, all you can say is that this nut was too unoriginal to think up his own method of killing somebody, so he had to use what was in the book.

Speaking of TV, how do you feel about the current state of the art?

King: I think we’re seeing the death of established television. It’s happening right now. You know, network TV is like this big dinosaur stumbling around. When I was growing up, TV was a dominating factor, at least in my life. Ed Sullivan on Sunday night, Maverick, Sugarfoot.

Pure entertainment.

King: Yes. You know, Route 66 raised the consciousness of every white kid in America. You found out there was a different way to live than taking college courses and getting out and going nine-to-five. And what have my kids got? B.J. and the Bear.

What about television’s use as a political instrument?

King: It can be argued that Kennedy was the last president to be elected pretty much without TV being the overmastering factor. So that once TV began, there were no more good presidents. And every time we elect a new president, we get further away from real politics and real people and more into the world of guest-of-the-week on Three’s Company. (Mimics) “Oh, guess what, Suzanne — the president’s coming for dinner. We’ve got to clean the place up!” And then the president comes in, and he’s somebody from Central Casting that you’ve seen on soap operas, with silver hair. Till, finally, we come to Reagan, where the TV image and the politician meet, and we’ve got an ex-movie star in the White House who, when he speaks … God! he looks so good; he looks like he’s trustworthy. But you look into his eyes for a long time, and … (hums theme from Twilight Zone).

Politics runs through your novels almost as much as another King favorite, religion. Is that a particularly horrifying part of your life?

King: It scared me to death as a kid. I was raised Methodist, and I was scared that I was going to hell. The horror stories that I grew up on were biblical stories. “Lo, the false prophets shall be thrown into the lake of fire!” and “Lo, he shall burn there forever! “ — and this kind of thing. They were the best horror stories ever written.

If you had to single out the scariest one of them all…

King: Lot’s wife turns back to look at Sodom and Gomorrah after she was told not to, and she turns into a pillar of salt. I used to pretend I was one of these guys running away and could hear the city burning behind me and the screams and the bolts of fire coming down from Heaven — I could feel my head go “Booooom!” Scared the shit out of me. So maybe it’s an obvious connection between what I’m trying to do now and what it did to me as a kid. But it’s also an effort for me to get around this whole business about religion and death and what comes after death and all the rest of it — and to try to make some decisions for myself.

Have you become more of a skeptic in the process?

King: No. I’d say I’m probably more religious now than ever in my life. I don’t go to church or anything like that. Organized religion is always the same thing: sooner or later, somebody drives a sword through your heart. They cut you up. They put spikes in your eyes. It’s always the same; it’s never really altered very much.

Is there any aspect of it you find more tolerable?

King: Everything that I see about organized religion appalls me. Jerry Falwell appalls me on the tube. He amuses me as well, but he mostly just appalls me, because there is kind of an intransigence there that’s almost beyond my ability to comprehend. That is to say, there’s no way to engage in a dialogue with Jerry Falwell. Anything that he is doing is right simply because he says it’s right — and he’s standing there in the middle of the church. I don’t see any difference between him and the Reverend Moon. Falwell says that sex books like Penthouse should be taken off the lower racks, where little children can look at depravity and barnyard sex acts and words and all this other stuff. Of course, he’s standing up there on TV saying this, and never in my life have I ever seen a Penthouse magazine down there where three- or four- or five-year-olds could grab it off the shelf. They don’t do that. It’s a lie. The guy is lying.

Are you on their hit list?

King: No. I’m well liked by the fundamentalists, and I should be, because my own views are pretty fundamental. But when I see Jerry Falwell get up there on that TV in that $300 suit, I say, “Fuck you! Get off!” I don’t know where their money comes from, but I think that if their books could be opened, you might find they might top the Mafia as far as the money that comes in is concerned. It’s all money, it’s all imperialism, it’s all America Firsters, it’s all a bunch of fascism. They’re living off people’s fears.

And yet there are people who say you do the same thing.

King: I don’t think that I really prey on people’s fears, because people who are fearful don’t want to have anything to do with what I write. They don’t go to horror movies either. It’s like the roller-coaster rides at the amusement park. People who ride the roller coaster aren’t the people who are afraid of it. They may relish the drop in their stomach or may scream because they are afraid when they are on the ride, but that’s a kind of courage in itself. The people who are really afraid are the ones who walk up to me and say, “Gee, I don’t read your books. I watch the ’Praise the Lord Club.’” In other words, the reason that people like Jerry Falwell can afford to say “I don’t listen to my critics” is because the people who are watching him don’t listen to his critics. They love him; he loves them — there is basically a religious circle jerk going on here.

How do you feel about the influence organized religion exerts on topics like abortion and gun control?

King: And the electric chair. They like the electric chair.

Where do you stand on capital punishment?

King: I don’t feel very good about it. I can think of isolated cases where I wouldn’t feel bad if a person was executed.

King: Although I’m not a New York State resident, I would feel infinitesimally easier in my mind if Son of Sam were fried, if David Berkowitz were fried. I feel both for and against capital punishment. The same way that I am very much against abortion. I hate the idea. I do think it is murder. I think when you kill potential, it’s murder. At the same time, what Falwell and some of the others are saying is that we have to legislate this. And the Bible — the supposed word of God — is based very firmly on one thing: free will. And, basically, what these people are saying when they say we’ve got to outlaw abortion on demand is that we have to outlaw free will. It’s an anti-God statement.

They’re also very firm on the issue of gun control.

King: I think that I would like to see permits needed to get any kind of a handgun. You’d have to have your picture taken. You could not have any kind of a criminal record or a record of mental illness, beyond having seen a psychiatrist, in the last six years.

Does that mean you favor gun control?

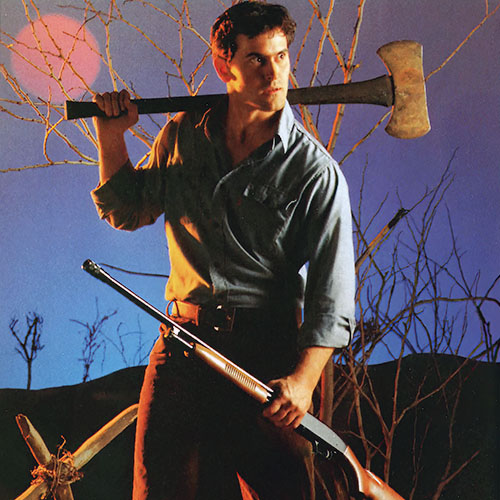

King: No. I want people to be able to go out and get a shotgun or a rifle if they want to go hunting. I can’t see Mark Chapman walking up to John Lennon on the street with a 410 shoved down his pants leg and managing to pull it out, cock it, and shoot the guy. I mean, Jesus Christ! I don’t think that we should have a tight, nonbending gun-control law in this country, but I think it’s time to put some curbs on handguns. You see all those bumper stickers that say: “If guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.” Well, that’s fine with me.

While were on the subject of control: why is there very little graphic sex in your books?

King: Well, there has been some … in The Stand, and I think there is some in Carrie. But Peter Straub [author of Ghost Story] says I never wrote a sex scene because “Stephen hasn’t discovered sex yet.” Actually, there’s sort of an unpleasant sex scene in Cujo which shows that Joe Camber fucks the way he eats, the way he deals with everything else: almost machine-like. But one of the reasons that I shy away from sex is that it’s such an elemental act, and the physics of it are so familiar to everyone that it is hard to do in a novel way.

But isn’t sex a repressed horror for a lot of people?

King: Yeah. There are all sorts of possibilities there.

If you had to write a horror novel that dealt with your greatest sexual fear, what would it be?

King: A couple of things. The vagina dentata, the vagina with teeth. A story where you were making love to a woman and it just slammed shut and cut your penis off. That’d do it. I’ve just completed a book called Different Seasons, and one horror story in it is about a pregnancy and is called “The Breather Method.”

You’ve mentioned Penthouse Forum in two of your books — Firestarter, Danse Macabre …

King: Along with everyone else, I believed the letters were staff-written. And finally I changed my mind. But I don’t think that most of the things happen. I think they are fantasies.

Healthy fantasies?

King: Sure. I would say that 90 percent of them are healthy. And some of them are tremendously clever. I’m kind of glad that Forum got away from the amputees and all that stuff.

No, I love Forum for one reason. It’s because, sexually, I’m not terribly adventurous — which is to say that there are no orgies in my life. I’m faithful to my wife. I don’t go out when I’m in a strange city and get four dollies off the street and say, “Let’s have a menage a trois or Dom Perignon in your snatch”— or something like that. I like sex very much, and I’m highly sexed. I’d just as soon screw a lot, but compared with Forum, that’s a little bit like saying I like steak and potatoes. And then you go into a fucking delicatessen and see people do that! I probably would never do it, because I would be embarrassed, or that Republican thing in me would come out, and I’d say, “Well, you’re not going to get me into that rubber diaper.”

I think a lot of people might say they read Stephen King novels for the same thing.

King: They can identify with it; they probably would never go out and do it.

Like moving your family into a deserted hotel in the Rockies to begin work on a novel.

King: We moved to Boulder, Colorado — not to a deserted hotel in the Rockies. We lived in a boring little tract house. We did spend one night, though, at a hotel. We were the only guests, and the wind was howling outside, and we were just on the edge of Rocky Mountain National Park. You could look out the window and see the snow, so many feet down. The corridors were long and mazy, and the orchestra was still there, playing, echoing. Just like the film.

Word has it that you weren’t terribly excited over the film version of The Shining.

King: I wasn’t unhappy with it. Kubrick’s a really smart man, and he made a really smart film. I don’t think it’s terribly successful, because horror is such a fucking hot medium. You have to be emotionally involved with. the people for it to work; you’ve got to be a warm, even hot, human being. And Kubrick’s not. He’s very cold, so you don’t care a lot about the people, and without caring it’s hard for horror to happen. I wish that he had done it in a different way, but being Stanley Kubrick, he probably wasn’t capable. A lot of filmmakers — in fact, most filmmakers — are pinheads. They have no brains. They can’t read; they can’t think. All they can do is visualize pictures on the screen. These pinheads read [my] books and say, “I can see that. I know what that looks like.” But just because you can see something it doesn’t mean that you know what it means.

Were you happy with Jack Nicholson in the film?

King: In an unfortunate sort of way, he’s been typecast as a crazy, like Bruce Dern. There were other people in my mind for that role. There was never anyone else in mind for the role in Warner Brothers’ mind. Nicholson’s name was brought up again and again. “It has to be Nicholson. It’s Jack. Jack is bankable. It’s got to be Nicholson.” And I kept saying, “No, no, no. He’s not right for the part. He’s too old now for the part. He has a certain image as someone who’s crazy, somebody who might be dangerous. He’s not ordinary enough.” They didn’t hear. They literally did not hear.

I wanted Michael Moriarty for the part very badly. He played this Nazi on TV who was also a family man who loved his kids. That was part of the horrible dichotomy of the situation in The Shining.

“If somebody does something based on what you wrote, all you can say is that this nut was too unoriginal to think up his own method of killing.”

Did your readers feel cheated by Kubrick’s interpretation?

King: Oh, yes! You should have seen the fan mail. They were furious with the movie. For a while there, the letters came in like Niagara Falls. I don’t know what kind of mail Kubrick got, but I got hundreds of letters a week from people who were foaming. I was stunned by the vehemence. People said that they wanted to string him up, that he should never be allowed to make another movie, that someone should give him a lobotomy before he struck again. Fury. Utter fury.

While we’re on the subject of people interpreting your work in other mediums, what about all the Stephen King imitators that are suddenly jumping on the bandwagon?

King: There are quite a few. I don’t know — most of them aren’t any good. They have a hard time taking the material seriously.

Maybe they’re too bright. You get the feeling that they are stooping to the material. Maybe they are not having enough fun. Maybe they do it for the money.

Several critics have accused you of the same misdemeanor.

King: When people say that, they are so wrong — they are wrong across the board. That’s the elitism that’s inherent in most of the reviews. You can always tell a bad review coming, because it will be a review of my checkbook and my contractual agreements. A review like that will start out saying, “This is the third book in Stephen King’s multi-million-dollar contract for New American Library,” and then you know, well … the trouble’s going to start.

Care to mention any of the bankable rip-off artists we should stay away from?

King: I won’t mention any by name. But I see a lot of books that must have been inspired by some of the stuff I’m doing. For one thing, those “horror” novels that have gerund endings are just everywhere: The Piercing, The Burning, The Searing — the this-ing and the that-ing. It’s a little embarrassing in a way, because The Shining was a title that I originally turned down. When I turned [the manuscript] in, it was “The Shine.” The contract had been issued that way. And one day we were sitting around talking about it, and the sub rights guy at Doubleday said, “Are you sure you want this book to go out under this title, with a black cook in it?” And I said, “What do you mean?” He told me that in World War Two, a shine was another pejorative that meant the same thing as nigger or coon. He said it was short for “shoeshine boy.” I didn’t know that, and the others in the conference room dismissed it.

I wasn’t afraid. that people would think that I was a racist; I was afraid that people would laugh at my not knowing. And, so, at that point, I said, “Let’s change the name of the book.” It was very late. They were getting ready to go to press and were setting the plates. And I said, “Suppose we call it The Shining?” And I just changed a few of the references in the book, changed the heads on the pages. And they said, “Okay.”

Do you usually encounter problems in coming up with the right title for a new book?

King: Well, I’ve finished a book about five kids who are mostly rejects. They were kids in 1957, and the idea of the book is that they’ve grown up and have to come back to this town where they grew up and discover, as a result of phone calls that are made to them, that they have completely forgotten a whole year out of their childhood. They realize that something awful happened and that they have to go back and face it again. I got everything in this book. I got Frankenstein, Jaws, the Creature from the Black Lagoon — fucking King Kong is in this book. I mean, it’s like the monster rally. Everybody is there. I thought it would be a good one to go out with. Called It. I should call it Shit.

Should you with to refresh your memory about Michael Moriarty, Mr. King’s preference for the Jack Nicolson role in “The Shining,” we have made that easy, Should you simply wish to catch up on what fresh horror is this with Stephen King, we made that as easy as clicking a link. as well. Finally, although it might be a tad out of character for us here, but for those of you unfamiliar, a little education vis-a-vis “The Twilight Zone” theme couild be helpful here. If you do not have a YouTube Premium account, you will need to wait five seconds before skipping the ad — sorry about that — but after you do it will start immediately. Everyone needs to be aware of this theme music, we believe. You will find in useful in your everyday lives. Honestly it should be playing every time you turn on the news these days.

Also, if you read horror at all, you really should read It. Anyone who reads can tell you: Watching the movies doesn’t count. (And, yes, we know we just put an “also” after a “finally” in these notes. Sometimes we get carried away. It happens.} [The event, not the scary clown. -Ed.]