Moonshiners have ruled in Franklin County, Virginia, for almost 300 years. But now, once-fearless bootleggers are on the run — pursued by a deadly combination of yuppie money and high-tech law enforcement.

Fading of the Black Pot [Moonshine] Kings

Franklin County, Virginia, likes to call itself the “Moonshine Capital of the World,” a title acquired during Prohibition, and in Rocky Mount, the county seat, you can see the prideful, nostalgic displays. At the one bar in little Rocky Mount, a well-lit place called lppy’s, there are framed yellowed photos of grim revenuers and gallon jugs floating down streams, and over the door, nailed to the wall, is a mock-up of an ancient copper kettle.

Though today moon-shining is hardly as widespread as it was even 20 years ago, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms estimates that the federal government loses close to $3 million a year to the unregulated, untaxed booze that still flows from Franklin County. The business persists largely because local justice has always been soft on moonshining. When a bootlegger went before the court, he could expect a nominal fine or a few months in jail. He usually faced jurors and even judges whose fathers and grandfathers brewed corn into liquor; they tended to sympathize. But the tide has turned against this way of life. In Rocky Mount — population 5,100 and growing — the signs on Main Street say Welcome Technology! The sons don’t study distilling anymore.

And now they’ll never get a chance, even if they wanted to. Two years ago, in the summer of 2000, agents of the ATF swept into Franklin County determined to put an end to the sacred business once and for all. The “bastard federals,” as some here call them, had spent three years quietly infiltrating the last of the big-time moonshiner families in a massive, unprecedented investigation dubbed Operation Lightning Strike. It wasn’t long before the guilty verdicts rolled in and moonshining in Franklin County was declared dead.

Operation Lightning Strike applied tough federal money-laundering, conspiracy, and racketeering statutes against what the ATF described as a “rural organized crime ring” centered in Franklin County and stretching across the Virginia — North Carolina “Whiskey Belt.” The two-dozen men in the Franklin County mob are believed to have pumped some 1.4 million gallons of “white lightning” into East Coast cities during the nineties. Their main markets were black slums where retailers sell dollar shots in “nip joints,” the backs of bodegas, and bars. The trade is lucrative: A 100-proof gallon costs just $3 to make and can fetch up to $16 in the city. One Franklin County setup was believed to have churned out 4,000 gallons a week — a profit of $52,000 for seven days of work, or $2.7 million a year. By contrast, the average worker in Franklin County makes $364 a week in lumber mills or textile factories.

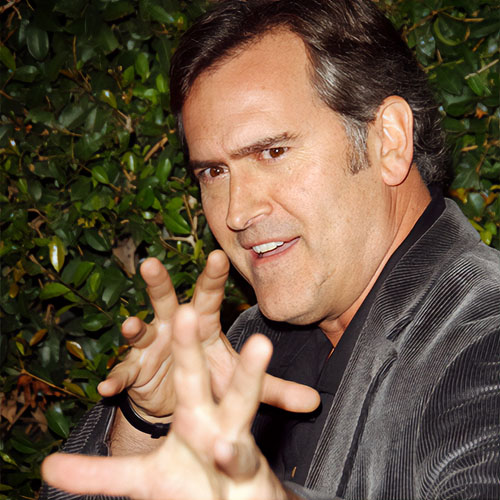

The lead “bastard” in the moonshine crackdown, mustachioed 37-year-old ATF Special Agent Bartley H. McEntire, says that in recent years moonshiners have modernized: They carry police scanners and cell phones, wear night-vision scopes out at the stills, keep coded ledgers, and launder their gains by recruiting wives and children and cousins to buy farmland and pickup trucks. “These guys are no different in their tactics from a drug cartel,” says McEntire. “For the first time we’re treating them as such.”

McEntire’s men tapped phones; they subpoenaed bank statements, vehicle registrations, canceled checks — unheard-of in Franklin County, where cops either caught you red-handed or they didn’t catch you at all. In July 2000, 20 defendants from Franklin County and elsewhere were indicted on charges of money laundering, liquor manufacturing, and a host of lesser offenses. These were whole families, the whiskey-baron dynasties that had the cash to set up the stills, and the contacts in the cities to distribute the product.

Now the barons were facing the rest of their lives in federal prison. They talked of fighting the charges, but when the evidence came before the judge in U.S. District Court in Roanoke, it was clear the case against them was impregnable. So they folded bit by bit and pled guilty.

I asked McEntire, who grew up in a small Whiskey Belt town in North Carolina, about the sour reception these arguably laudable efforts have had in Franklin County. “It’s always amazed me when people say there’s nothing wrong with moonshining,” he said. “And then you look at the people involved in it; it’s a history of shooting and killing each other going back generations. Moon-shining has been destroying generations of families.”

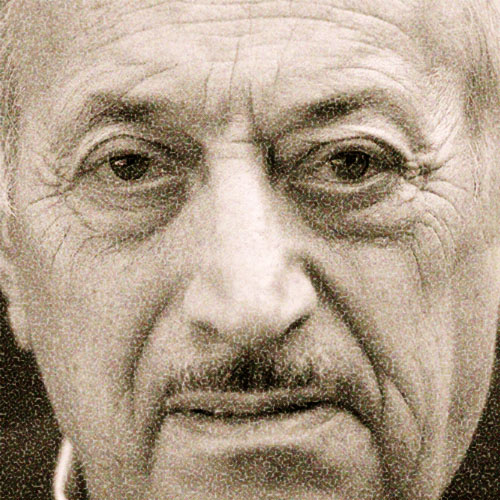

“Operation Lightning Strike was unlike anything the government had ever done,” Morris Stephenson, a crag-faced Franklin County newspaperman, told me. “There was a gentlemen’s agreement between the law and the boot-legger, about what the law could and couldn’t do. The law never cuffed the bootlegger or brought him in. They said, ’Meet us at the court at 9 A.M.’ There was a way of doing things here that didn’t exist anywhere else. But now it’s all changed, and it’s put a fear in everybody’s heart.”

Well, not everybody. In the boomtime Clinton years, Franklin County became two counties — two peoples, really — geographically and culturally at odds. In the western, mountainous half, there is Appalachia: old moonshiner villages like Endicott and Ferrum, hardscrabble places squirreled away between rocky blue peaks. You head east and notice that the land is gentler, the earth richer; there are Subaru Outbacks and new BMWs, and the drivers are no longer wearing Valvoline caps, but caps with names of colleges.

The eastern half of Franklin is now the prime asset and growth engine of the county, and this is thanks almost entirely to the deep manmade waters of Smith Mountain Lake, the product of a dam built in the 1960s. In the early nineties the real-estate marketeers saw dollars on the lakefront. In the past five years development around the lake has exploded, drawing middle-class northerners, rich by Franklin standards, looking for vacation homes or a place to retire, attracted by Franklin’s low taxes and cheap land.

As a result of the land rush, Franklin County now has the second-fastest-growing population in Virginia, and it’s also suffering a full-blown identity crisis, with one half clinging to the past while the other steadily erases it. At lppy’s, I over-heard the language of Franklin’s future: two men in suits speaking of “information services” and “business systems” and “establishing market leadership.”

John Chauncey Moore, 54, a retired surveyor, was sitting nearby, drinking a beer. “My family came here from Scotland in 1844,” Moore told me. “We started making liquor long before Prohibition. In 1908 and 1909 the farmers were given free land, but it was all rock, every two inches was schist and flint. But we had the water, the clean water — sweetwater, they called it — that ran in the streams.” The water, brewed right, could turn a meager corn crop into a year’s equivalent of maize at market.

“Moonshine built Franklin County,” Moore said. “It was the income from moonshine that helped start the lumbering and the furniture industry. To get into the lumber business, you had to have the money to buy the trucks — and that was moonshine money.” That same money, Moore said, filled collection plates at churches, helped families through bad winters, and covered mortgage costs when the crop failed, as it so often did.

“The whole county’s in transition now. This Operation Lightning Strike had all sorts of political and cultural overtones. It was something that had to be done — to change what goes on here — because the county needs the money coming from the north. The newcomers, they won’t abide having a neighbor making liquor next to their $250,000 home.”

The county’s chief lawman, Sheriff W.Q. “Quint” Overton, a tall, silver-haired 65-year-old who wears no uniform except cowboy hats and gray suits, told me about the old days. When I met him in his tiny offices near the Rocky Mount courthouse, he was talking with his friend Dickie Atkins, a 53-year-old moonshiner from Endicott who was finishing up a short sentence for parole violation in the county jail. Atkins looked pale and thin in his jail blues. He is a purebred, a progeny of the business, and you can hear it in his mumbled musical Appalachian twang, which transforms a phrase like “I remember everything” into “Ahm’ber ay-ee-thain.” Atkins’s father was a notorious bootlegger and trigger-happy gunman who killed four men (and some say more). Dickie himself once shot a man three times in the stomach with a .357 magnum during a drunken duel. He has spent 15 years of his life behind bars, mostly for driving much too fast and without a license.

“Remember when you rolled that ’56 Ford, Dickie?” Overton said. Atkins said “Hell!” and the sheriff told the story. “There was a robbery near Dickie’s house and we set up a roadblock thinking the perpetrators might come back down thataway. And here comes Dickie, movin’ — roarin’ — someone recognizes him, and we realize, well, damn, he’s gonna run the roadblock. So we put a shotgun hole that big in the side of the engine” — the sheriff spread his hands about two feet — “the car rolls down the hill there, and Dickie jumps out at the last minute. That’s Dickie for you.”

Atkins looked proud. “You remember, Sheriff,” he said, “when you stopped me and found those jugs of liquor, and you just sent me on my way? Hell, when you did that, I knew you was a good man.”

Their amity was part of that old gentlemen’s agreement, begun in Prohibition and unbroken for 70 years. It was part of the Code: The sheriff did his job, the moonshiner made it a hard job, and there was no bad feeling on either side. If the bootlegger got caught he went along quietly, and the sheriff returned the favor. Often enough, the moonshiner and lawman drank together off-duty. And though it was odd at first to hear the sheriff commend a man who ran his roadblocks, this too was part of the Code. It was what “the McEntires up there,” as the sheriff put it, would never comprehend, with their search warrants and wiretaps.

“Listen, I’ve raided more stills than McEntire’s ever seen,” the sheriff said. “On my second night as a state trooper, I was smack in the middle of a whiskey chase, gunnin’ down the road. In the sixties I was raidin’ two stills a day: Get out there and run ’em down! See if they can swim! And I jumped in the river and ran ’em down. But these people are human beings, and I don’t hold it against their standing ’cause one of ’em’s trying to make a few extra dollars. It is a violation of the law, sure — but I say they’ve [only] violated a tax law.”

“The law never cuffed the bootlegger or brought him in. They said, ‘Meet us at the court at 9 A.M.’ But now it’s all changed.”

The Code was built on these distinctions, and at bottom it meant that local law regarded moonshining as a crime only insofar as it cut in on the government’s liquor monopoly. Rapists and thieves were a different matter; these were fundamental enemies of society. Tax thievery, on the other hand, was the flip side of an original theft — tax itself. Sheriff Overton’s comment was steeped in history and called back to his forebears. The raw and ready Scotch-Irish who settled the mountains of Appalachia and brought to America the art of home distilling in the early eighteenth century were the same breed that spawned the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. The rebellion was a watershed of how federal power would be used: The nascent U.S. government levied stiff tariffs on Pennsylvania liquor; the producers bridled, championing states’ rights over federal dominion, and it required 13,000 soldiers from New Jersey to put down the insurrection.

That fierce blood ran in Dickie Atkins. Three days after he got out of jail, Atkins did something moonshiners almost never do for strangers: He took me to a still deep in the woods — not a working still, but one that had been popping and fuming “not long past” — to explain firsthand how good “blackpot” liquor gets made. In the moonshine hierarchy, Atkins is what they call a “still hand,” a lowly laborer, the forest grunt who hauls in the grain and mixes the mash among the mosquitoes for $100 a day — an expert chemist, in his own way.

On a sunny Saturday morning we got in his truck and went west, to Endicott, along wild roads paved in S-curves over moraines and bowls and knobs, deep into the mountains, through Scotch pine and cedar. The high-walled hollows of Endicott swallow the sun even at noon; the land turns dusky and forbidding and lets out sweet smells. As a ‘shiner once put it, “A man just can’t help making whiskey up there.”

Dickie Atkins has cracked up at least a dozen times moving liquor. He has meaty scars along his legs and arms from the accidents, and the lid over his right eye hangs unevenly, as if the flesh had melted and quickly froze. It gives him a sinister look.

“Now we come one day into this curve here,” said Dickie at a turn that was frightening at 20 miles an hour, “at about 110, full open, ’63 Chevrolet, flipped it, put holes in the top of the car. Over here, we had a ’66 Fairline, flipped it, hit a lightpole. My friend died, got his legs crushed. Right over here we were driving an ’85 LUV truck. The guy with me later drank hisself to death.”

We went on into the mountains. We drove along an icy brook, bumping and grinding queasily on mud ruts. We walked through the backwoods past a cousin’s trailer home, past the corpses of at least 50 cars hunkering on a hillside without tires, or inexplicably on their backs like turtles. We finally came to the “still place,” now a ruin of metal and wood under a broken tin roof. Axed and dismembered by the feds, it was one of Dickie’s last outfits — he even had a name for it: “the Shady Cabin.” To set up another still this size can cost $10,000, and Atkins doesn’t have the cash. He picked over the mess in silence, toeing the blackened metal, grunting once and shaking his head.

Generally, stills come in rigs of 800-gallon units lined up in rows; the largest rig ever discovered was a 36-unit operation in Pittsylvania County, Franklin County’s neighbor to the east, a few years ago. The units, known as black-pots for their fire-scorched underbellies, are eight feet long and four feet wide, and are hand-fashioned out of galvanized aluminum or steel supported by two-inch-thick hardwood siding.

An 800-gallon blackpot, Dickie tells me, will produce about 80 gallons of liquor per “run” (production cycle), and if you work it right, you can get two or three runs — some 240 gallons — from a single pot of mash. Summer’s the best time to do it, he says, because cold weather impedes the fermentation process. To make an 80-gallon run, a ‘shiner uses 800 pounds of sugar, 200 pounds of grain (corn if you want the better stuff), eight pounds of yeast, and lots of water. Then he “mashes it in” with a wooden fork, and lets the mix sit for three days. Within an hour a few bubbles break the surface, and within ten hours the mash starts to rise. It churns and patches and foams, and then suddenly it settles down. What’s happening is the starches in the grain are turning to sugar, which is speedily turning to alcohol, and by the time the cook comes back, he’ll have a fine “distiller’s beer,” about 24 proof, tasty enough but no more powerful than wine.

Now the ‘shiner gets a propane burner going under the blackpot, and keeps close guard of the temperature. Alcohol boils at 173 degrees Fahrenheit, water at 212 degrees, and he wants to navigate somewhere between, so that only the live alcohol steam boils off into the doubler barrel, known as the “thumper” — so-called because the steam from the boiling process makes a steady, sorrowful thumping against the metal. From the thumper the steam is forced by the heat and pressure through another pipe into the final processing unit, the “worm,” a copper coil immersed in cold water. The science here is simple: The alcohol steam, doubly distilled and super-potent, hits the cool worm, condenses fast, and from a spigot on the side of the worm box there flows a clear pissing stream of 200-proof whiskey, which then gets “proofed down” to about half that with successively weaker runs. The ‘shiner tests it by lighting a spoon dipped in the potion: Blue flame means it’s good.

“I made liquor first time when I’uz ten years old,” Dickie said. “My daddy told me he’d let me stay outta school and give me ten dollars. And then it was my life. It was natural every night: Filter 50, sometime a hundred cases, six gallons a case, when I was jest, hell, ten, 11 years old. I’ve seen about as much liquor come outta here as I have water.”

Dickie rooted about in the ruin, picked up a shard of copper coil, looked at it a moment, and dropped it back in the pile. “First time I drank liquor I was seven years old. I got drunk off o’ raisin brandy, on a Sunday. I fell off the porch and passed out and ended up in the hospital and asked my mother was church over with, and she burst out crying. My daddy damn sure found out, ’cause he was the one paid all the bills, but he didn’t get angry. One night we had 50 cases of liquor to fill, and I was in the yard runnin’ barefoot, cut my foot, and he had to bring me to the hospital and wouldn’t get to fill that 50 case of liquor. He raised a little hell about that. Yeah, we made some good liquor, me and Dad. Lot o’ liquor. Don’t matter now, I guess.”

Then Dickie became quiet. We got back in his truck and drove toward the heights of the Blue Ridge Skyline Drive, which bounds Franklin County on the west, and I asked him where his father was now.

“My daddy was killed on Friday September the Tenth of 1976,” Dickie said. “The other guy said that Dad shot at him first. But ain’t no way in hell my dad missed a sonofabitch 15 foot off. My dad — by God, you ask Sheriff Overton — my daddy could shoot a goddamn .38 like no other. Dad was walking out of the house, and the guy was standing behind the damn car with a damn 12-gauge shotgun, and he shot Dad down. I went over there to Dad’s house, by God, and had a pistol down my britches, and I didn’t even see my dad laying there dying.”

The road became pebbled and rutted, the ravines dropped into emptiness out the window, and the pickup swayed like a rowboat in surf. There was a long silence. “Past ten years, everything’s really changed, you know?” Dickie said. “Now it’s the driest it’s ever been. I wouldn’t know where to get a decent drink in Franklin County. It was good back when. I know. Lord, I know. Makes me sick thinkin’ about it. There jest ain’t the people around like there used to.”

After about a mile, we coughed out onto the well-paved Blue Ridge Skyline Drive. There were tourists on foliage cruises, in sedans, peering out windows, and some were in sports cars and wanted to go fast on the tight turns. Dickie was driving like an old man, and a guy in aviator glasses honked for him to speed up or move over.

Ah, the joys of progress. These days you can buy your own moonshine still and have it delivered right to your door from Amazon. You can find dozens (at least) of online stores that will happily ship your their version of mooshine in all sorts of flavors that would spawn scorn in any self-respecting mountain outlaw. (Never in history has anyone said, “Hey, Bubba? Y’all figure maybe we ought to try some cinnamon in this Lightning to give it a pleasing aftertaste?”)