Despising their genitals and social roles, they are men who want to be women, women who want to be men.

Transsexuals (50 Years Ago)

In the United States there are thousands who live among us in fear and waiting, racked by the torment of being sexually displaced persons. Known as transsexuals, they are convinced they belong to the opposite sex and are driven by a compulsion to have the body, appearance, and social status of that sex. They live and pass in their adopted roles, and often attain hormonal, surgical, and legal sex reassignments.

One of them is Alice, whom you may have passed on the street with barely a glance, never suspecting his agony. Alice was born a male but always felt he should have been a female. He got hold of estrogen, the female hormone, when he was twelve by telling a veterinarian he needed it to castrate a stallion. Instead he injected himself, in a desperate attempt to enlarge his breasts, widen his hips, and shrink his unwanted penis. When that failed he tied one end of a string to his penis and the other end to a doorknob and slammed the door. It was not an attempt at self-mutilation as much as an act of pathetic frustration. His penis survived, and it was another decade before Alice was castrated by a surgeon’s knife and finally found peace. Transsexuals such as Alice, who are convinced they are the wrong sex, who despise their genitals and their social roles, who dress in the role of the sex they wish to be (known as crossdressing), seldom find happiness without sex-change surgery. Seeking other routes, some marry, and many seek therapy. But those marriages made before surgery almost never last. Psychotherapy has failed them miserably.

“I tried to live as a woman, and even married a man,” says Robert, a female-to-male transsexual in Oakland, California. “But for me to put on a skirt and go with a guy was a homosexual act. Sex with a man made me sick to my stomach. Teenage sex problems are bad enough, but when you don’t even know for sure what sex you are, they’ re hell.”

Transsexuals cannot be dismissed as “sick.” In fact, most are diagnosed by psychiatrists as healthy and nonpsychotic. But, of all who are outside the sexual norm, they are the least understood. They are different from the transvestite, the man who wears women’s clothing as a fetish to turn himself on, but who may still enjoy intercourse with women. They differ, too, from the male homosexual “drag queen” who parades in female clothing as a charade, a mockery of women. They are not homosexuals who prefer lovers of the same sex. Transvestites and drag queens don’t always mind being “read” or recognized on the street as being of the opposite sex. But transsexuals dread it. They want to be women or be men.

Transsexualism begins in children who are too young to understand the sexual implications of their genitals. Dr. Richard Green, the thirty-six-year-old director of the Gender Identity Research and Treatment Program at the UCLA School of Medicine in Los Angeles, is studying fifty feminine boys aged four to ten who began crossdressing regularly before they were six years old. He began the study in 1968, and has recorded his initial results in his recent book Sexual Identity Conflict in Children and Adults (Basic Books).

His young patients have an interest in women’s clothing that borders on obsession. They use towels for wigs, T-shirts for dresses, and crossdress secretly if parents object. The “normal” male child tries on mother’s heels or her dress to see if he can make it across the room without breaking his neck, and then goes out to play ball. But the children in Green’s study shun rough-and-tumble sports, take the role of mother or sister when playing house, and prefer dolls to other toys.

Green and his colleague, Dr. Robert Stoller, professor of psychiatry at UCLA, found that some of these children come from families where the mother dominates and often feels depressed or worthless. The father is often physically absent or emotionally withdrawn, or is a superstud so threatening that his son shuns things that seem masculine. The mother often touches the child excessively, makes no demands on him, and tends to his every need — in effect keeping him in a womblike state. “She holds her perfect child in an endless embrace,” says Stoller. “As a result, her son does not learn where his own body ends and hers begins.”

“Transsexuals are the Uncle Toms of our society; they believe the stereotypes and are conservative in most things, including sexual relations.”

There is little comparable research on the female-to-male transsexual, partly because four times as many men as women with transsexual problems seek professional help. Sex experts believe there are fewer female-to-male transsexuals because it is more permissible to grow up as a tomboy than as an effeminate male in our society. Also, boys have to go through the complicated process of breaking away from the mother’s pull before they can adopt their own masculine identity — a process girls are able to bypass. Transsexuals say there are just as many female-to-male as there are male-to-female transsexuals, but that they stay better hidden. In any case, most parents ignore early signs of transsexualism. They wait until the child is eight or nine years old before bringing him or her in for treatment, and by then it may be too late.

Transsexuals who are not helped may go so far as to sacrifice, through surgery, their capacity for normal sexual enjoyment in order to live in a comfortable role. “When gender is your problem, there is no release from suffering. I was willing to do without sex rather than keep my genitals,” says Alice, the twenty-nine-year-old male-to-female transsexual who tried to castrate herself. (Because Alice has completed sex-change surgery, I will refer to her as female from now on.) “All transsexuals pray ‘Dear God, make me a woman.’ But if they woke up one morning with a vagina and breasts, but still had to wear male clothes and play the same male games, they would not feel God had answered their prayers. Culture is more important than genitalia.”

Sex experts agree with Alice. They point out that the surgical vagina created in the male-to-female transsexual, although it can often function like a normal vagina, may be constructed poorly and is easily infected. The female-to-male transsexual must be content with clitoral orgasms, even if he has a surgically constructed penis. All efforts to create a functional penis through “phalloplasty,” or skin grafting, have failed and any resulting appendage is only for show.

Transsexuals often consider the day of surgery as their real “birthday.” For all practical purposes, Alice was born on the operating table at the age of twenty-six: she changed not only her sex but her birth records, her job, her name, her home. As an effeminate young man growing up in Boston, Alice had lived a life of isolation. Friends and family mocked him. He moved to the West Coast, married a woman whom he considered “like a sister,” then had sex-change surgery and now lives with her “wife” on a farm, where they rear the wife’s child by a previous marriage and breed timber wolves for a living.

“I tried for twenty years to conform to masculinity, but I failed miserably. I always looked like a girl,” says Alice. “Besides, I came from the classical transsexual background — a dominant mother and a weak and absent father. He died when I was nine.”

Alice also works with psychiatrists in the private West Coast university where she had her sex changed. She helps to screen transsexuals who apply for surgery there: criteria for acceptance are the intensity and duration of the emotional pain. “Nobody knows anything about sexuality, that’s the problem,” she says bitterly. “But transsexuals know about loneliness. Loneliness shoots right through your soul.”

Alice carries her femininity with confidence, and the once — shy man now comes across as a no-nonsense woman. She slaughters her own beef, chops wood, and paneled her own living room. She favors blue jeans and turtleneck sweaters. Her only jewelry is a women’s liberation medallion — a clenched fist in the center of the female symbol. She carries herself with grace, however, and wears a hint of pink lipstick. Above Sophia Loren-like cheekbones created by silicone, her big brown eyes sparkle generously and often. Only her thick wrists and muscled shoulders give any hint of her past.

Alice’s wife, Jane, is a tall, slender woman with a peaches-and-cream complexion, fine features, and deep red hair. Alice and Jane were friends and occasional lovers (although never in the strictly heterosexual sense, because Alice never used her penis for sex) long before Alice had the operation that transformed her to a woman. Their marriage, one of convenience, enabled Jane to keep her daughter by a previous marriage. She married Alice knowing full well about the planned surgery. Neighbors believe they are sisters, or lesbians. “Most male-to-female transsexuals find themselves attracted to women,” Alice says. “After all, they have been beaten by men, mocked by men, for all the early years of their lives. I put up with their persecution for twenty years. How can I like men now? I stay with Jane because of her sensitivity — she gives me a sense of security. We have a hell of a lot more in common than most men and women living together. We don’t have sex anymore, although we like to cuddle.” At this point, Jane interrupts. “I was married for five years the first time,” she says. “And I don’t understand how any woman can live with a man.”

The masculine role threatened Alice while she was living as a man, yet she feels free to act more masculine while living as a woman. “I’m just learning,” says Alice, “that just because I haul a shovel doesn’t mean I’m less feminine.” Yet she refuses to cook or clean in her own home, as if that would make her too feminine. She reads feminist books, but also hangs a girlie calendar above the kitchen sink. In fact, she’s a male and female chauvinist at the same time.

“My wife and I are often in competition with each other for men,” she says. “We go to bars together and see who can get a man first. I usually do. Men say they’re more comfortable talking to me. I think it’s because I have a male brain, even though I definitely view myself as a woman. It’s easy to take the average woman and make her come unstrung. Not me. From the time they are little, women are taught to be quiet, subdued, non-competitive. At least I wasn’t subjected to that as a child. I can usually talk women right out of a conversation.”

And what happens when she gets the man in bed? “One guy was really on a breast trip, and he turned me off. So I figured he would be a good one on whom to spring the fact that I am a transsexual. At first he had the usual male reaction, put his hand to his head and said, ‘I can’t believe it!’ Then we went to bed and we did the whole bit, cunnilingus, everything, and it didn’t make any difference at all. In fact, the best sexual experience I ever had was with a man who never even got into me at all. Frankly, he was too big — ten, no, ten and a half inches. But he was great. I think the ideal lover would be a man without a penis.”

Alice is generally pleased with her new life, although she did go through a period of depression for a few months following surgery. “It’s a very confusing thing to be given your dream. You ask yourself: now what? But after the initial panic, you learn to take pride in your new womanhood,” she says. “I look at it in terms of the alternatives. I could spend the rest of my life socially paralyzed, miserable, or begin my real life a quarter-century after I was born. We transsexuals go through a lot of persecution, and if we survive at all we end up indestructible. Dorothy here would be dead by now if she hadn’t been strong.” She nods in the direction of Dorothy, a frail young man in woman’s dress, a houseguest who has been quietly listening to the conversation.

‘Marcello is a short, fat man with beefy arms and a full black beard. He is an ex-nun. “I was also very religious then. But I learned you can’t hide from God.”’

I refer to Dorothy as “he” only because he hasn’t yet had surgery; he’s a china-doll of a woman, slightly built, painfully shy, with a wispy voice and alabaster complexion. He was born to a family in a small conservative Wyoming town, which was always unreceptive to his persistent tendency to act female. He was once attacked by neighborhood boys who stuck pins in his genitals, but the physical pain was slight compared with the emotional trauma. “When my mother died, I was seven, and my family claimed she died because I broke her heart,” Dorothy says. He went to a small Western college, but couldn’t stand the incessant taunting. Now he is receiving hormone treatments and electrolysis to remove facial and body hair before going through transsexual surgery.

The movement of his hands, the sway of his hips, the lift of his chin — once sources of ridicule — now save and comfort him. In order to live socially as a woman, he has given up family, friends, education — his entire male past. The “roles” of male and female are so divergent, so alien, that Dorothy can find no alternative to surgery — the most drastic solution to his obsessive search for perfect femininity. This search is an all-consuming effort including a total awareness of body language, makeup, clothing, speech patterns, and habits.

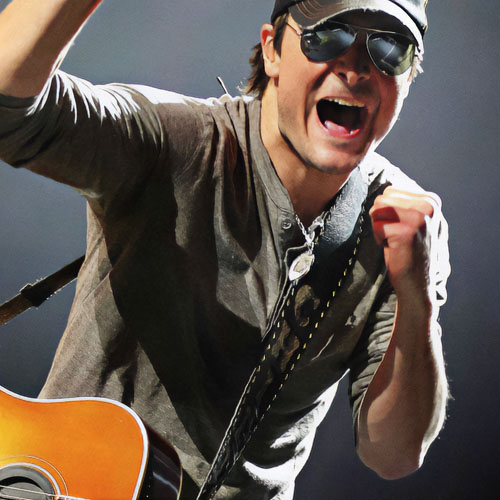

“Play-acting is an important, probably a basic part of transsexualism,” says Dr. John Money, professor of medical psychology and pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and an expert on transsexualism. “They learn gender roles just like we learn a language. Children with early manifestations of transsexualism are especially adept at role-playing, just as children are especially fluent in languages they learn at an early age. From childhood, transsexuals have this burning ambition to play a role they’re not. As adults, a disproportionate number go into drama and theater, because when they finally achieve their goal to live as a different sex, when they’ve proved they can do it, that’s the show-the-world phenomenon, the theatrical part.”

A large proportion of male-to-female transsexuals do show off their new bodies by going into burlesque, topless dancing, or prostitution. Fellow transsexuals, especially female-to-male transsexuals, often denounce this sexploitation, afraid that it will create a bad image for those who want to merge anonymously into middle-class life. “Transsexuals,” Alice says, “are usually the Uncle Toms of our society; they believe the stereotypes and are conservative in most things, including sexual relations.” This is especially true of the female-to-male, who usually tries to blend in with WASP suburbia. But in a continuing effort to reaffirm their new femininity, many male-to-female transsexuals offer their vaginas and breasts up for male adoration. Most were doing similar numbers before surgery; after surgery they simply do it with more relish, for they no longer need to use tape or Kotex to bind their detested male organs. Now, with nothing left to hang out, they can let it all hang out.

Regina Renee “lived in drag” (dressed as a woman) for twenty years before she had sex-change surgery on October 12, 1972, at Yonkers Hospital in New York. Now thirty-nine, she is manager of the R.A.R. Night Club in Philadelphia, which uses her transsexualism as a drawing card, and occasionally she dances at other nearby clubs. “Men say they like me because I’ve been on both sides of the fence,” she gushes when we meet. “And I’m a 44D — be sure to put down the D part. Don’t I have a beautiful body?” She spins around on her sandals; her body is striking indeed. She carries a 44-26-40 on her five-foot ten-inch frame, accented by a barely buttoned pale pink blouse, size 38, and equally tight slacks. Her long silver hair, part real, part wig, is heavily teased. She wears thick pink lipstick, and large gold hoop earrings dangle from small, close ears that are also a product of modern medicine. The change of sexual identity, including a new nose, ears, cheeks, and five years’ worth of female hormones, cost her about $15,000. Surgery and the hospital stay alone were $3,500.

We spend a night on the town in staid and quiet Philadelphia: first, coffee in a gay restaurant, followed by dinner with a man in conservative business suit who drives us around town in his black Lincoln and who, Regina confides, is her longtime bisexual friend; next, a tour of two gay bars — Land of Oz and then Harlow’s, which is presided over by another transsexual, Harlow, a stunning Vogue-fashion type who also uses her transsexualism to promote bar business; finally Regina meets a blind date — a construction worker supposedly ignorant of her sexual history — at the bar of the Rickshaw Inn in nearby Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

Regina is bold, brassy, and, to her detractors, a gaudy symbol of the image most transsexuals wish to avoid. But she is very much her own woman. “We all have God-given rights to be individuals. Our Constitution guarantees it, although it doesn’t always protect it,” she says. “But I have a way of getting what I want. And I wanted nothing worse than surgery. Mockery only made me stronger, more determined than ever to get it.”

She denies any misgivings about her operation. “I lived thirty-eight years as a man; that’s enough,” she says. “When I finally decided on the operation, I got the $3,500 to pay for it in three months — I have a few nice gentlemen friends who were, shall we say, kind,” she winks. “I never used what I had, never enjoyed sex before surgery, and you don’t miss what you don’t use. Now I enjoy it tremendously; I jiggle in all the right places, and in bed I am ultra-unreal. I have complete vaginal muscle control. Of course, I don’t spread it around. I sit on it and cherish it. But I do love flattery. I love to turn men on, to listen to the street-corner comments. What woman doesn’t — even if she’s ugly?”

In the bathroom of the Rickshaw Inn, she insists on showing me her vagina; before I can protest, she unzips her slacks, pulls them to her knees, and spreads her vaginal lips so I can see that it does, indeed, look just like the real thing, complete with pubic hair and some penile remnants that vaguely resemble a clitoris. One female-to-male transsexual nurse told me later he couldn’t stand male-to-female transsexual patients like Regina. “Their whole life generates from the vagina,” he said. “They run up and down the hospital corridors bragging about their new boxes. And nobody’s life emanates from between the legs, I don’t care what you say.”

Satisfied that I have seen her inner plumbing, Regina returns to the bar in high spirits, and insinuates to the construction worker that she and I are very close friends. “He thinks we’re lovers, isn’t that funny,” she finally turns to me and mumbles gleefully, hand coyly in front of her mouth. “I drive men wild, can you believe it?” she whispers. A woman on the small stage a few feet away from us is in the middle of the song “I Did It My Way,” filled with overtones the lyricist never intended. Saturated by Regina’s sexual fantasies and the young man’s diligent efforts to bed her, I hover between laughter and tears when Regina turns once more to me. “Relax, enjoy yourself,” she admonishes. “Let me tell you, honey, life won’t wait for you, you have to grab it and enjoy it.”

Regina’s life has been anything but fun. She was born and reared in a Pennsylvania coal-mining town, with seven sisters and three brothers. The sisters were closer to her in age, so she played house with them. “I was very good in school, but I quit because the kids were making fun of me,” she says. “It was mental torture.” …

“When I was eleven, I realized I was a girl. I started to dress in drag when I was sixteen, and never went out of it after that. My mother loved it; she said I looked a million times better. My father, who was a mechanic, thought it was sick. But my mother was the boss. My father died when I was twenty-one, and my family’s been 100 percent behind me ever since.”…

A child’s basic gender identity, or sense of itself as male or female, is almost completely formed within the first thirty months of life, and attempts to change it later usually end in trauma. There are two aspects to this identity: chromosomes, hormones, and genitals determine sex; social roles taught from birth determine gender. When sex and gender agree, the result is a male (sex) who is masculine (gender) or a feminine female. Problems begin when sex and gender disagree. There is, of course, no doubt that society plays a crucial role in our childhood development. But we now know that the fetus itself contains the seeds of dual sexuality, and that biology may play more of a role than we now suspect in determining our immunity or susceptibility to gender identity conflict.

At conception, the baseline of sexual tissue is feminine, which means it will develop as a girl unless it receives some male sex hormones in the womb. Whether it will receive the male sex hormone is determined by a set of double chromosomes: XX in the female (the second X is necessary for the ovary to fully differentiate) and XY in the male (the Y is necessary for the testes to differentiate). If the embryo is programmed by its XY chromosomes to develop as a male, it will normally receive these necessary male hormones from the embryonic testes during a crucial point in fetal development, believed to be around the third month. But even the XX and XY chromosomes do not guarantee that the proper hormones will be administered or that the baby will be born with its genitals intact. If no male hormone is added during development in the womb, or if the fetus is unable to use the hormone, it will not masculinize, even if it is a genetic XY male. On the other hand, if too much male hormone is added to a genetic XX female embryo, the external genitals will masculinize, although internally the baby will have a uterus and ovaries. Accidents of this type occasionally happen, producing a genetic man with a uterus, or a genetic woman with a penis. These “intersexuals,” sometimes called “hermaphrodites,” have special biological problems that, if handled properly, do not have to lead to transsexualism.

Suzy, for example, was born a normal male, but was accidentally castrated during circumcision at the age of seven months. The parents brought their baby to Dr. Money at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. There it was decided to rear the child as a girl, and when Suzy was twenty-one months old, doctors performed initial surgery to reconstruct the genitals. Money reports in his book Man & Woman, Boy & Girl (Johns Hopkins Press), which he co-authored with Anke Ehrhardt, assistant professor of research in the departments of pediatrics and psychiatry at the State University of New York at Buffalo, that Suzy is now six years old and is “feminine” by the doctors’ definitions — which means she likes frilly dresses, dolls, and helping her mother around the house. She feels like a girl in every way.

To the delight of science, Suzy has an identical twin brother, reared as a boy, whose childhood progress has also been followed. He has developed into a completely “masculine” boy — which means he likes to roughhouse and play with tools. He defends his sister against all who threaten her.

Another intersexual, Tom, thought he was a normal boy until the age of eleven, when his breasts began to develop. When his parents took him in for tests, they learned their son was really their daughter, who had received an extra dose of male hormone while in the uterus. As a result, the baby was born with both a normal-looking, although small, penis, and with a uterus and ovaries that began secreting estrogen at puberty. Under Money’s guidance, Tom decided to change his anatomical sex to match his male gender, and surgeons have subsequently removed his female organs. Now, several years later, Tom has girl friends in high school, races motorcycles, and is described by his doctors as a “gung-ho boy with no qualms about sexual relations.”

Until recently, most of what we have learned about fetal sexual development comes from laboratory reports of the effects of sex hormones on unborn rats, guinea pigs, and monkeys. When injected with sex hormones of the opposite sex at critical times in their growth, these animals develop not only ambiguous genitals but also bisexual behavior. Female monkeys injected with male hormones will act like males, will be more aggressive and rough-and-tumble in their play, and will mount other females. Male rats injected with female hormones will “mother” their young. Researchers now believe that animals in the lower orders have the capacity to act out male or female roles, and the sex hormones simply change the thresholds of the brain centers that control such behavior. The more complex the animal, the more varied the response.

Money and Ehrhardt took this research a giant step forward and applied it to humans. They studied twenty-five girls born with somewhat masculinized genitals caused by excess androgen in the womb. They found that according to our cultural stereotypes of femininity the girls were more “tomboyish” than a matched set of “normal” girls, which meant they were more dominant and energetic, preferred team sports over dolls, wore more practical clothing, and valued a career over marriage. Money and Ehrhardt also tested ten genetic males who were unable to respond to the male hormones in their system, much as some diabetics are unable to use the insulin produced by their bodies. The ten males had been reared as female because they lacked external male genitals. They tested out — again under the old stereo-types — as extremely “feminine”: they all wanted to be wives and mothers, and preferred playing with dolls to other games. Other feminine boys reared as boys were studied by UCLA’s Dr. Richard Green and two Stanford psychiatrists, Irvin Yalom and Norman Fisk. They studied forty boys born to diabetic women treated with female hormones during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage. The boys were less aggressive, less assertive, and poorer athletes than a control group of boys not exposed to the hormones. The psychiatrists caution that the study is inconclusive, for chronically ill mothers could tend to overprotect their sons and interfere with their “aggressive” development.

It is dangerous to draw sociological conclusions from these biological data, and sex researchers know this. When sex researchers turn to cultural stereotypes as a basis for defining biological man and woman, they expose themselves to charges of chauvinism. Parts of sexual learning were undeniably imprinted into our psyches from the time of primal ooze: in lower animals, such as monkeys, newborn males are more aggressive and newborn females are more submissive. Closer to home, males in childhood and man-hood almost always have penile erection during that stage of dream sleep called Rapid Eye Movement (REM) — indicating that dreaming and sexuality may be linked neurophysiologically. Extra doses of the male hormone androgen before birth may raise IQ, and during adulthood may increase the sex drive in both men and women; this would indicate that the hormone does affect the central brain system. But how many conclusions can be drawn in a field where fact and fantasy make such appealing bedfellows?

Most of what experts thought they knew about sexuality has already turned out to be myth. The idea that all women suffer from penis envy, that women are limited to only vaginal orgasms, that pornography leads to sex crimes, that women don’t respond to sexy stories and pictures — all these ideas have been destroyed by research. Conclusions on sexuality run the risk of being self-fulfilling prophecies. Sex researchers try to step gingerly around the dilemma, which is like trying to swim without getting wet. Money, for example, points out that the only unalterable biological differences between sexes is that women menstruate, gestate, and lactate, and men impregnate. Simple enough; but even these boundaries can be hedged. His book Man & Woman, Boy & Girl discusses a multitude of cases such as those of Suzy and Tom, mentioned above, who were born in a gray sexual area that defies such easy definitions.

Feminist sociologist Alice Rossi of Goucher College, in Towson, Maryland, studied 15,000 women college graduates. Her original conclusions were sociological: the deviant 10 percent of the women who chose careers over marriage and wanted small families came from homes with an unhappy marriage, a dominant working mother, and an unsuccessful father. Then she read Ehrhardt’s studies on androgen levels, and now hypothesizes that these women could also have excess androgen. “Many of my feminist friends consider me close to a traitor,” she writes in the book Contemporary Sexual Behavior (Johns Hopkins Press), and she concludes that so little research has been done on the conflicting roles of biology and environment that she cannot flatly reject a possible hormonal influence on human sexual behavior.

All of this is academic to transsexuals, who have more practical dilemmas to live with. These are more often social than sexual. “I work in a world where the other guys would just drop dead if they knew about me,” says Marcello, a female-to-male transsexual who works for a staid New York insurance company. “My wife and I have the respect of our neighbors, we have friends and co-workers who respect us. That’s what life is all about. If I exposed the truth about myself to them, I would be ruined,” he says.

Marcello is an ex-nun. He lives with his wife, Norma, in a lower-middle-class suburb of New York City. They were married shortly after his sex change in March 1969. Like most female-to-male transsexuals, Marcello embraces middle-class values. He wants desperately “to belong.” He is proud of his conservatism, and says he understands why neighbors would look askance if they knew about his past life as a woman and a nun. “My attitudes are chauvinist and old-fashioned,” he says. He counsels other female-to-male transsexuals at the local hospital, and they share his views. “Most transsexuals believe deeply in stereotypes, in the validity and viability of sex roles — they become ‘super’ males and females. I believe my wife should cook dinner and I should be the boss. What’s wrong with that?

“My wife and I are like everyone else, except we have no children.” Well, almost like everyone else. The large poster over his kitchen table says: “Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not.” Marcello shows me pictures of several other female-to-male transsexuals and their wives, which he keeps in a photo album beside his own wedding pictures. Some of the “men” are strikingly handsome. “Those transsexuals having surgery at the age of twenty-one have it made,” he sighs. “They are young, and can be fathers to children who have been conceived through artificial insemination. But we did it at the other end of the age spectrum; I’m thirty-six and my wife is thirty-three. She’s too old to have a first child.”

Marcello is a short, fat man with beefy arms, a full and curly black beard, hairy chest, thick facial features, and a deeply bubbling laugh. His wife, a nurse at a nearby hospital, is a thin, pale, and silent woman, who looks older than her years. She met Marcello eleven and a half years ago, when they were both in nurses’ training together. At the time, Marcello, still a woman, had just left the convent. “I told Norma the first day I saw her that we would become close friends,” he says. “At that time, neither of us knew just how close.”

Marcello says he entered a convent out of frustration, an inability to fit in anywhere else in society. His Italian father heartily approved. “I may have gone into the convent because the habit was one way to camouflage my body, which I hated,” he says. “I was also very religious then. But I learned you can’t hide from God. I finally decided to leave after two and a half years, because of the utter frustration at being aroused by women, the other nuns, who surrounded me.” Like many female-to-male transsexuals, Marcello has remained religious. “I feel God really exists, and wanted these things to happen to me,” he says. “He’s given me some pretty rough blows, but he’s also given me the strength to deal with my problems. All in all, he’s treated me fair and square.”

Marcello remembers being aroused by women during his childhood in Gary, Indiana. “When I was small I dreamt I was going to marry the lady next door and kiss her and kiss her — that was my idea of marriage then,” he laughs. Like other transsexuals I met, he had no sex education as a child. “I experimented in sex with the little girl next door. When we played, I was always the conductor on the train, the daddy in the family. My father was a cop, an Italian cop. He was dominant in my family; you know — the same old story. You take on the characteristics of the dominant parent. He communicated with the back of his hand. My mother died when I was twelve, my father remarried and sent me off to boarding school.”

“I heard about Christine Jorgensen shortly after that, and used to go to bed praying I would wake up in the morning as a man.” (In 1952, a GI changed his name to Christine Jorgensen, bleached his hair blond, had a sex-change operation in Copenhagen, and then told the world about it. She was the first transsexual to acknowledge her problem and her solution in public. Now in her mid-forties, she does some off-Broadway theater and makes appearances around the country to discuss her book The Christine Jorgensen Story.) “I went into the convent, then into nursing, but I couldn’t escape my feelings,” says Marcello. “I finally tried intercourse with a guy when I was twenty-two, just to see what it was like, but he couldn’t penetrate me because I was a virgin. When I was thirty years old, I finally found someone to listen to me — Dr. Harry Benjamin.” Benjamin, a pioneer in the field of gender-sex research, coined the term “transsexual” in the early 1950’s following the Christine Jorgensen case, in which he was a consultant.

Marcello’s father was bitter about the surgery, and died of a stroke two months after. Norma’s parents, who own a farm in Kentucky, are gradually getting over the shock of their daughter’s marriage to a transsexual. “I would never have told them, they would have never had to know, if Marcello hadn’t gone home with me to visit them when he was still in women’s dress,” Norma says. “Their main concern was that our relatives and friends would recognize him when he returned as a man. But we’ve visited them several times, and so far no one has.”

They lived together for eight years before becoming legally married following Marcello’s surgery. Most of that time they lived hidden in the urban anonymity of Manhattan, where neighbors wouldn’t bother them. “Our marriage was a great relief. Other marriages fail because people are young and must deal with new problems of growth within marriage. All our problems came before; first we built the house brick by brick, and now we live in it.” Since Marcello never considered himself a woman, he never considered their former relationship as lesbian.

So far he has had a mastectomy to remove his breasts, a hysterectomy to remove his female organs, and hormones to promote the body hair and deep voice. He does not, however, have a penis. Last year doctors tried to graft skin from his thigh into a tube that resembled a penis, but it shriveled up. “I knew I was a guinea pig. It will be a while before I get up enough nerve to go through another try, though. I still recall the pain and horror of it all.” He considers the abortive surgery a minor part of the price a transsexual pays for a new life. “You have to consider the price of moving, of changing your name, the money lost by going from job to job covering up your past, the weeks you lose from work while you’re in surgery.”

The “great feelings of frustration” he has about his missing appendage are more social than sexual, he insists. “It would be nice to be able to talk about sex exploits with the guys. If you have a nice one, there’s nothing wrong with throwing it around a little, showing it off. I don’t mean you should flash it around, but if someone sees it in the bathroom or dressing room … well, you know it’s something you can be proud of.” He must use the stalls in the men’s bathroom when he wants to urinate. But he insists his sex life with his wife is not really hindered. He can still have clitoral orgasms, as can his wife. “Our sex life is just fine,” Norma says. “I don’t feel I need a penis to be sexually fulfilled. Marcello is tender and sensitive in bed, and knows what pleases me.” And for her added pleasure he has developed a “prosthetic phallic device” which he calls a PPD — an artificial penis made of silicone that looks like a dildo but has a vaginal “plug” that fits snugly into the vagina of the female-to-male transsexual. It can be used both for urination and intercourse, says Marcello, but would be inconvenient to wear all day because it is always erect. Marcello plans to begin selling them soon at $125 apiece, but only to other transsexuals. “This is a medical prosthesis. It will not be for the general public,” says his advertising flier.

At least five hundred transsexuals have already had sex-change surgery in this country, many of them at Johns Hopkins, which opened the first gender-identity clinic in 1966. And the phenomenon is not unique to the United States. Dr. Roberto Granato, a New York urologist who has performed more than one hundred male-to-female transsexual operations in hospitals in the New York City area, says he receives calls “every day” from transsexuals or their psychiatrists in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Canada, and has been asked to consult in South America and the Netherlands. The Erickson Educational Foundation in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which disseminates information and supports research on transsexualism, reports there are now more than thirty gender clinics in this country. But only a dozen surgeons have had experience performing transsexual operations here. Doctors told me that because of American eligibility requirements, only one in ten who request the surgery receives it; many go instead to Tijuana or Casablanca, where doctors do a healthy business in sex-changes.

All those who receive surgery must meet certain requirements. They must go through at least one year of psychiatric evaluation, live in their chosen sex role for one year, have a complete check of their endocrine glands to be sure nothing is physically wrong with them, and complete a series of hormone treatments — the female-to-males receive male hormones to lower the voice and grow body hair, the male-to-females receive female hormones to raise the voice and round out the breasts and hips. The male-to-female also needs painful and expensive electrolysis treatment to remove facial hair, and often wants silicone implants in the breasts and cheeks and plastic surgery on the nose, Adam’s apple, and sometimes ears. “In sum,” says Granato, “by the time she gets to me, I want the patient to be a woman with a penis.” The female-to-male is required to have a hysterectomy and mastectomy.

Transsexuals are also expected to pay the surgical and hospital fees prior to surgery. These usually run around $4,000 for the male-to-female procedure, and around $6,000 for the more complicated female-to-male procedure.

While reputable doctors insist their patients follow the above procedures before surgery, some transsexuals say anyone can get surgery if they’ve got the cash. Some insurance companies in some states cover the cost of the operation. Some states will also put the patient on “total disability” welfare while they are changing sexes.

The surgery itself is painful, bloody because of the spongy tissues involved, and not always successful. In the male-to-female operation, which takes about two hours, the testes are removed and either the penile skin or a graft from the thigh is used as a “sleeve” to line the artificial vagina, which surgeons create by cutting into the body at the position of the normal female vagina. The sensitive scrotal skin that contained the testes is shaped into a clitoris. The patient is kept in the hospital for about a week, but is required to wear, for four to eight months, a vaginal “stint,” a piece of foam rubber or plastic that keeps the vaginal canal open. This is worn a few hours each day until the vagina is completely healed.

The results can be good enough to fool gynecologists and lovers. Almost all male-to-female transsexuals can achieve orgasm, thanks to a psychological phenomenon called “metaplasia,” in which grafted tissue gradually takes on the characteristics of the tissue it is supposed to replace. “Almost 100 percent of the patients have a fantastic ability to have orgasm,” Granato says. Bit by bit, the inverted penile skin begins to lubricate itself during intercourse, acting like a normal vagina. The remaining atrophied internal male sex organs also help out occasionally by emitting small amounts of ejaculate. The prostate gland, which is situated behind the new vaginal skin, and the urethra at the top of the vagina are also erogenous areas, especially when friction is created by the thrusting motion of the penis.

Unfortunately, the female-to-male operation is not as satisfactory, because no one has yet been able to produce a functional penis through surgery. Not all female-to-males insist on a genital construction, since the male hormone testosterone administered by mouth and injections often enlarges the clitoris enough for a tiny but highly sensitive penis-substitute. The artificial penis, for those who want it, is usually created by cutting a flap of skin down from the belly and molding it into a suitable shape. The center is left hollow so a stiffener can be inserted for intercourse. The labia majora are converted into a scrotum, and silicone palls are implanted for testes. The clitoris is left intact, because it remains the only source of orgasm. The results are usually dissatisfying to doctor and patient alike. The males never escape the frustration of incomplete sex organs. “The males are really obsessed with their sexual inabilities, although it doesn’t seem to bother the wives,” says Dr. Benito Rish, a New York plastic surgeon who has operated on more than a hundred female-to-male transsexuals. “Postoperatively they quiet down for a while, but then they begin talking again about their frustrations,” he says. “There is not much feeling,” agrees one newly created male in Oakland, who is nonetheless enormously pleased with the esthetic results. “It is much like screwing with a dildo.”

The most logical solution — penile transplants — does not seem feasible at this time, doctors say, because it would involve attaching dozens of small blood vessels, many more in number and smaller in size than those involved in heart transplants.

But surgeons define the overall success of these operations in terms that encompass more than just their technical skills. “The most important factor of success is the patient’s mental attitude,” Granato says. Rish agrees. “The transsexual’s problem must remain on the operating table. The only criteria for success,” he says, “are the overall appearance of the surgery and the psychological makeup of the patient.” Surgeons and psychiatrists would like to follow the mental health and social lives of their patients after surgery, but seldom do, for most patients move away, change their names and lives, marry, and try to forget about their past. “I never discharge them. They just don’t come back,” Granato says.

There are occasional rumors of postoperative transsexuals committing suicide, but the overwhelming majority seem happier after the surgery. I could find only one case in medical literature describing a male-to-female transsexual who changed his mind after the operation. She was reoperated on for conversion back to male, then changed his mind again and was operated on for a third time to become female. Doctors feel, however, that such ambiguity over sexual preference indicates the person was not really transsexual and should never have been operated on in the first place.

While gender-identity conflict may upset middle-class morality, those who would like to classify the transsexual as sick will find little support among those psychiatrists who work with them and counsel them. Dr. Richard Green, who is also editor of the medical journal Archives of Sexual Behavior, explains it this way: “A psychotic person would say, ‘I am a woman. I know I have ovaries, I menstruate every month from the tip of my penis or under my fingernails’ or wherever. That is psychotic. But the usual transsexual says, ‘I know my body is that of a man but I feel better living as a woman, I want my male organs removed so I can live as a woman.’ That’s not psychotic. And if you want to define their desire to change their sex as psychotic, then you have to create a whole new definition of psychosis. You could perhaps call it ‘true paranoia,’ which means someone holds a circumscribed false belief, like the delusion that they are, for example, Napoleon. But there is no evidence that giving a person a Napoleonic costume makes them psychologically healthier. That’s not true with the transsexual. It does seem that surgery makes them psychologically healthier.” In many ways, then, surgery “cures” the transsexual like aspirin relieves a headache. It takes away the pain.

‘Most male-to-female transsexuals find themselves attracted to women. After all, they have been beaten by men, mocked by men, for all the early years of their lives. I put up with their persecution for twenty years. How can I like men now?’

Transsexuals, of course, throw a wrench into the traditional definitions of homosexuality and heterosexuality. We do not know, for example, whether a male-to-female transsexual who takes a male lover is homosexual before surgery and heterosexual after, or if sex with the lover would be homosexual in both instances, or heterosexual in both instances. We do not even know if our own sense of masculinity or femininity is defined by chromosomes, by genitals, or by gender — or which of these factors is more important, or how many can be absent and to what degree before we cross that hazy line from one sex to another.

Although no one knows yet how to completely avoid gender-identity problems, there are optimum environments for minimizing the chances that they will appear. Children, says Green, should be able to witness occasional parental nudity as a natural part of family life. Based on his case histories, Green concludes: “Occasional nudity is a visible clue to the child, helps him or her categorize his or her own anatomy and start working on a basic sexual identity. The genitals are important for the child, not initially for sex but for gender. Children should be able to look with pride on their bodies, then develop behavior from there.” Doctors agree that the mother does not have to be a genetic female or the father a genetic male to be a good parent, as long as they look, talk, and behave in ways consistent with their gender. “It doesn’t matter,” Money and Ehrhardt concur, “if the father cooks the dinner and mother drives the tractor … so long as there are clear boundaries delineating, at a minimum, the reproductive and erotic roles of sex.”

There is little hope of spreading this information quickly to other professionals, however, since there is still no department of sexology or sex research in any American college. Those probing the mysteries of transsexuals still spend much of their time seeking money to support their work. Private foundations are traditionally reluctant to dole out grants for sex research. Budget slashes in the National Institute of Mental Health, one of the few sources for sex-research funds, threaten progress for the next few years. “My grant has one year to go, and it is very doubtful I will get the money I need to continue my work beyond that,” Money says. Green faces the same problem.

But, despite these handicaps, the United States is still ahead of other countries in the sex-research field. “Sex research is a made-in-America venture,” says one expert, “largely because of our puritan history. Our society is less casual about the sexual, which makes it so important. We Americans are fascinated with organ-grinding.” Other sex experts, however, feel the U.S. excels in sex research simply by default: this country spends more public and private funds on all forms of medical research, and although sex research gets only a tiny portion, it is still more than most other countries can afford.

One need hardly be an aficionado of politics in order to understand the seismic shift in attitudes towards not only transsexuals but anything related to gender identity issues over the past few years. That topic would be way too vast to even approach in a footnote, but we can offer a place to start with a general approach and even legal avenues if you find a need. … Amazing what has — and has not — changed in the 50 years since Penthouse first published this, right?