“I’ve worked very hard my entire life to maintain a good reputation and in just a few minutes it was destroyed…. I went from being Mr. Clean to being a hood.”

Penthouse Interview Wayne Newton

If you’re intrigued by singular careers, consider Wayne Newton’s: During his more than 35 years in show business, Newton has had just two major hit records-“Danke Schoen” and “Red Roses for a Blue Lady” — has rarely appeared on television, and has never starred in a movie, Yet he’s somehow managed to become the nation’s No. 1 nightclub attraction. If you doubt that for a moment, you’ve never seen Newton work. In Las Vegas he’s billed as “The Midnight Idol,” and for nine months a year, seven nights a week, two shows per night, there’s never an empty seat at one of his performances. For more than a decade, it’s been sold-out performances for Newton to sing before Las Vegas audiences that are standing room only, and the same is true whenever he turns up in cities as diverse as Des Moines and New York. And let’s not forget Washington, D.C. Last year, when Newton worked the capital’s annual Fourth of July concert, his appearance at the Washington mall stirred up a storm of controversy that, among other items, briefly rekindled interest in the Beach Boys and also helped drive former Secretary of the Interior James Watt out of office. The Fourth of July furor wasn’t Newton’s first encounter with controversy. Four years ago, when he became part owner of the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas, NBC alleged that the singer was linked to organized-crime figures. Newton’s response was to file a lawsuit charging NBC with libel. The case is still in litigation.

Newton is probably the highest-paid cabaret performer in history — he earns more than $1 million a month in Las Vegas alone — and it’s due primarily to his ability to pack audiences in night after night, year after year. He’s also perhaps the hardest-working performer around today. While most stars are content to present shows that run 60 to 90 minutes, Newton’s performances last for at least two hours and sometimes stretch to three. Unlike most of his colleagues, Newton never does the same show twice. Currently, he opens with “C.C. Rider” and usually ends with “MacArthur Park” — and everything in between is up for grabs. The six-foot-three-inch singer’s repertoire includes more than 1,000 songs, and in the course of an evening he’s liable to range anywhere from “Only You” to “Oh Lonesome Me.” Newton’s eclectic musical tastes seem to include equal measures of country, folk, and rock music, but his favorites tend to be ballads, such as “My Way,” “Georgia on My Mind,” and “The Impossible Dream.” He also plays 11 different instruments, and he can fiddle with the best of them when it comes to a number like “Orange Blossom Special.” Additionally, Newton tells jokes, sings songs requested by the audience, kisses the ladies, shakes hands with the guys — in short, he’s a complete entertainer. Given his experience, that shouldn’t come as a surprise, for Newton’s been singing professionally almost all his life.

Born in Norfolk, Virginia, on April 3, 1942, Carson Wayne Newton is the son of a half-Irish, half-Powhatan father and a German-Cherokee mother. Newton learned to play guitar when he was four, and a year later he landed his first job singing at an AFL-CIO Christmas party. At the age of six, he and his older brother, Jerry (who accompanied him on guitar), were appearing regularly on a local radio show when Wayne came down with a serious case of bronchial asthma. Newton responded to penicillin treatments, but after three years he became immune to the drug. For the sake of Wayne’s health, the family moved to the dry climes of Phoenix, Arizona, when he was ten. Soon after arriving there, Wayne and Jerry appeared on a local television show and then began one of their own, for which the boys were paid $90 apiece. The show lasted four years, after which Wayne and Jerry auditioned for a job at Las Vegas’s Frontier Hotel and Casino. The Newton Brothers, as they were known, were given a two-week contract, at which point Wayne became a 16-year-old high-school dropout. He never looked back. The Newtons continued to play the Frontier Lounge 40 weeks a year for the next five years. In 1963, Wayne appeared on The Jackie Gleason Show and then recorded the song “Danke Schoen” — and the rest, as they say, is history.

To interview the 42-year-old singer, Penthouse sent writer Lawrence Linderman to meet with Newton during one of his rare national tours. Linderman reports: “I caught up with Wayne Newton at Atlantic City’s Resorts International Casino Hotel, where he usually appears a couple of times each year. Before we were introduced, I watched Newton run through a sound check with his orchestra in the hotel’s Superstar Theatre. Newton’s voice is unique: It’s very strong and husky, yet he can easily span three octaves — and that’s before Newton turns on the afterburners and adds another half octave with falsetto. His larynx is probably the size of an elephant’s.

“In any case, when we got together backstage, Newton was surprisingly candid and amiable. He has reason to be neither: Because of constant threats on his life, Newton travels with a team of bodyguards that is headed up by his chief aide, Mike ‘Bear’ Forch. Bear is to Mr. T (a former bodyguard to boxing champ Leon Spinks) what Merlin Olsen is to Howard Cosell. You do not mess with Bear. Nor do you attempt to mess with his employer, for karate is one of Wayne Newton’s major passions.

“Within minutes of our meeting Newton was ready to get down to cases. Newton’s controversial July Fourth Washington concert was still provoking inquiries wherever he appeared, and it provided the opening question for our conversation.”

Mention your name to most people and they still bring up the July Fourth concert you gave last year in Washington, D.C. When former secretary of the interior James Watt announced you’d been hired instead of the Beach Boys — because rock music “attracts the wrong element” — it seemed pretty clear that you agreed with him. Was that the case?

Newton: Of course not. No question in my mind that it was an offensive remark by James Watt, and he shouldn’t have said it. Watt, incidentally, never mentioned the Beach Boys by name, but still, there was no need to pit me against rock music. Hell, I’ve been singing rock ever since the first time I heard Elvis Presley.

.Penthouse: If you felt that way, why didn’t you speak out about it at the time?

Newton: I just didn’t want to add fuel to the fire. In my own mind, I was taking the high road, and that’s why I didn’t do any interviews about the concert. But by not doing any, in a lot of people’s eyes, I somehow became James Watt, and his critics decided they were going to get us both in one shot, sort of like killing two birds with one stone. Overall, that concert and everything surrounding it turned out to be one of the worst and, at the same time, one of the best experiences of my life.

Care to tell us how you got roped into it?

Newton: What happened is simply this: Last February, the Washington Parks Commission — not James Watt — asked me to do the July Fourth concert, and I accepted. Sometime after that, they told Watt, “Look, we know you wanted a charge of policy from rock groups, so here’s who we’ve picked to do this year’s concert on the mall.” Well, around April 7 or so Watt made his statement about rock groups attracting “the wrong element,” and all of a sudden there was hell to pay. Overnight it was me versus the Beach Boys and rock music. Now I don’t really think of the Beach Boys as a rock group, but besides that, the Beach Boys happen to be friends of mine.

How quickly did you realize that you’d inadvertently become a stand-in for James Watt?

Newton: Very quickly. A couple of days after his statement, I got a call from Nancy Reagan — I’ve known the president and the first lady for many years. She told me, “Wayne, I really apologize for this whole Beach Boys thing. I’m embarrassed and the president’s embarrassed, and we don’t want you to feel we did this to you intentionally.” I told her not to worry about me — and she laughed and said, “Well, other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?” I really wasn’t worried about the concert until three weeks later, when Frank Fahrenkopf, my attorney, called me from Washington. Frank said, “You’ve got a real problem with the July Fourth show. A radio station here has been running a campaign to get people to boycott your concert, and some people in Washington are actually making effigies of you and burning them. People who hate James Watt now hate you! I’m not kidding, Wayne — you better do something about this.”

Did you do something about it?

Newton: No, because it was a political football game, and I didn’t want to play. So I still refused to comment on it, but when I appeared at the Circle Star Theatre near San Francisco I called Mike Love up onstage with me. Nobody knew who he· was, so I said, “This is Mike Love of the Beach Boys, and we both want you to know that we’re friends.” Other than that, I just assumed that all the talk would die down. Boy, was I wrong!

Didn’t the Beach Boys themselves keep the controversy going?

Newton: Yeah, they did every interview they could about it — People magazine, TV newscasts, they did it all. But I didn’t get upset about them until they were invited to appear at the White House — now that pissed me off! I thought, “Here I am, being quiet, and taking the brunt of all this shit, and the Beach Boys are playing the White House? I thought the president and the first lady were my friends.”

Why did the Reagans invite the Beach Boys to the White House?

Newton: They didn’t. All the Reagans had done was offer use of the White House to the Kennedys for a celebration honoring the Special Olympics kids. Sargent Shriver or Teddy Kennedy — nobody knows which one — then decided to invite the Beach Boys as a slap at the Reagans. The Reagans didn’t know the Beach Boys would be entertaining until four days before the event. They’d simply said, “Here’s the White House, use it for a day, and we’ll be in attendance,” which was a nice thing for them to do. And then the Kennedys decided to shove it up their ass.

How sure are you about that?

Newton: I’m 100 percent sure of it, because I heard about it first from my lawyer and then from President Reagan himself. Just after the announcement about the Beach Boys was made, the president called me and asked me to come see him the next time I was in Washington, which I did. We met in the Oval Office, and the president told me the story. He said, “I don’t know how your concert’s turned into this, Wayne. You’ve been middled, and we’ve been middled — and poor Watt, he can take his own lumps, but he certainly doesn’t deserve this. I want you to know you have my backing, and if there’s anything I can do, name it.” I told him the visit was enough, and later that day I finally did some interviews about the concert. I met with reporters from UPI, AP, and a few newspapers, and all of them were just clawing at me to put Watt down. But I wouldn’t do it. I said, “As long as we’re being fair, I don’t need to be a spokesman for James Watt or for the Beach Boys. The Beach Boys have done two July Fourth concerts in Washington, and if the Parks Commission wanted them to appear again, I figure somebody would have called them.” Well, the press took off on me, and I started feeling there was nowhere for me to turn. I got back to Washington three days before the concert, and everywhere I went people came up and asked, “Aren’t you worried about appearing here when nobody wants you?”

Were you worried?

Newton: Damned right I was. The press was predicting the worst July Fourth show in Washington’s history, and they also predicted that there’d be riots at the concert. And then, on the day of the show, it hit me like a ton of bricks: The president and first lady were in California. It was called, “You’re on your own, kid.” I suddenly realized that my entire career could be on the line, because if that show was a bomb, I would have been the laughingstock of the whole fucking country.

Since you’re not, we take it the concert went well?

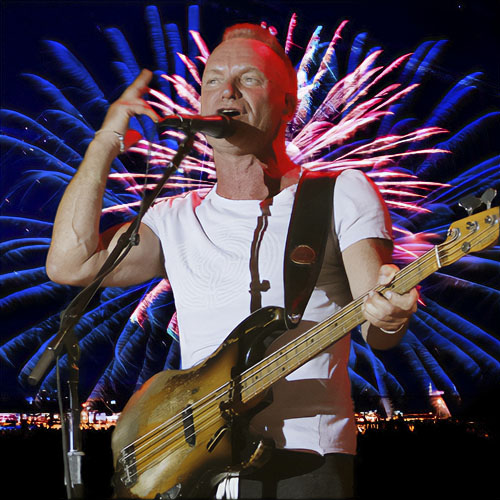

Newton: Let me tell you exactly how it went. At about three o’clock on the afternoon of July Fourth, a thunderstorm hit Washington, and I mean it was a down-pour that lasted for more than an hour. I hadn’t slept in two days, and at about six o’clock I turned on the TV— the concert was supposed to start at 7:30 — and there’s an announcer saying, “I’m standing at the Washington mall, and, historically, when the Beach Boys and other rock acts have played here on July Fourth, we’d probably be looking at 125,000 people by now. From what anybody can tell, there are fewer than 15,000 people here waiting to see Wayne Newton.” I looked at Elaine, my wife, and tears started to come down her face. I just said a silent prayer, got dressed, and then we drove over to the mall. When I got there it was about 6:45, and between the time I’d seen that TV newscaster and the time I got there, 200,000 people had shown up. I had a lump in my throat like you can’t believe. I think the record for the mall, which was held by the Beach Boys, was approximately 210,000 people. We ended up with a crowd of more than 325,000 people.

The concert itself went well?

Newton: When I finally got to sing, yes. But just as I was about to go on at 7:30, another rainstorm started, and it lasted for more than an hour. Nobody left, though, and I finally went on at about 8:45. When I walked out onstage, there was only one detractor in the crowd, and he was holding up a sign that said WE ARE THE WRONG ELEMENT. That was the only demonstration of any kind, and the sign went down after the first song. I ended the show with the American trilogy — “Dixie,” “Battle Hymn of The Republic,” and “America” — and when I got into “America,” the crowd, without being asked to, started to sing along. Just then it began raining again, and the harder it rained, the louder they sang. I had to quit singing; I just got too choked up. If all the adversity hadn’t taken place I’m sure it wouldn’t have been as meaningful, but all I can tell you is that it was a moment in my life I’ll never forget. And the next day, the press did a complete about-face. The Washington Post, which really had been laying into me, ran an editorial that said, in effect, that “Wayne Newton came here facing a great deal of adversity, caused mainly by the media, and he broke all records for the mall, and handled the adversity like the gentleman that he is.”

“I can’t tell you the kind of rejection I went through at the hands of the entertainment industry. I had Michael Jackson’s voice — but back then, all it brought me was attacks of vitriolic humor.”

You’re hardly a stranger to media adversity. In 1980, when you bought into the Aladdin Hotel, in Las Vegas, the NBC television network reported that you were heavily involved with organized-crime figures. We’re not trying to play prosecutor here but was there any truth to that allegation?

Newton: Absolutely not. NBC said I got financing for the Aladdin from the Mafia. That was the impression they gave, and for all practical purposes, that’s what they said. And that’s why I’m suing NBC for libel. When the case comes to trial — and we are going to trial, probably some time this year — we can prove malice, defamation of character, and real damages, perhaps to the tune of $7 or $8 million.

Why do you think these statements were made by NBC?

Newton: Because at that point NBC was renegotiating Johnny Carson’s contract and was trying to romance him into signing again — and Carson had tried to buy the Aladdin himself, but he obviously didn’t get it.

Why not? Did you outbid him?

Newton: No, I’d only made a backup offer, which meant that if Carson’s deal didn’t work out I’d be next in line. As it turned out, Carson and his partners were so cocky that after they cut a deal with the hotel’s owners they kept changing it, to the point where they left those people with no dignity. The Aladdin’s former stockholders finally said, “Look, if we’re going to give the hotel away, we’re not going to give it to you, Carson.” That’s how I wound up getting involved in ownership of the Aladdin: The former owners sought me out. I wasn’t standing in the wings talking them into throwing Johnny Carson out.

And you believe NBC then came down on you to placate Carson?

Newton: Yes, and I’m not trying to skirt your question, but for legal reasons I have to be careful about how I answer you, because the case is still going on.

Be as careful as you need to be, Wayne, but we’d really appreciate an answer.

Newton: Okay, here’s what happened: After the Aladdin’s owners threw out Carson’s bid in May 1980 and accepted mine, I had to be licensed as a casino owner by the Nevada Gaming Commission, which is standard operating procedure. My license hearing came up on September 26, 1980, in Carson City, and what happens at a Gaming Commission license hearing is that every aspect of a casino sale is made public, and even the Internal Revenue Service shows up. There were a lot of TV cameras in the room that morning, and when we broke for lunch, a local news-caster from Las Vegas came up to me and said, “Do you have a problem with NBC? An NBC-network reporter named Brian Ross is here to do a hatchet job on you.”

Did you think you had a problem with NBC?

Newton: I had no idea what the guy was talking about, but when I went back to the hearing room after lunch, I noticed that there wasn’t a moment when the NBC cameras weren’t running. They filmed everything that was said. Anyway, we completed the hearing that day, and the Gaming Commission’s three-man board voted unanimously to recommend licensing me. As I was leaving the hearing room, a man I now know as Brian Ross shoved a microphone in front of my face and said, “Mr. Newton, how do you feel? You must be elated.” I told him I was, and then, out of left field, Ross said, “Tell us about Guido Penosi.” I told him I’d testified everything I knew about Guido Penosi at the hearing — and I’ll tell your readers all about Guido Penosi in a few minutes, but let me first finish with what happened between me and NBC. Ross said, “Didn’t you call the sheriff of Las Vegas to get Penosi out of jail?” That never happened, and by then I realized I was being set up, and that this was an ambush interview. So I told Ross I had nothing more to say to him, and my attorney and I walked down a flight of stairs and then down a long hallway — at which point Ross and Ira Silverman (an NBC news producer) came running after us. Ross caught up to me and asked me,

“Who is Frank Piccolo?” I’d never heard of Frank Piccolo, and told him so. Ross then said, “Connecticut?” I said, “Yes, I’ve heard of Connecticut.” While Silverman filmed the proceedings, Ross badgered me all the way down the hall, and finally I stopped walking and put my arm on his shoulder. I started to say, “Listen, pal, do me a favor — this is not the place for an interview. If you’re so intent on interviewing me, we’ll find a room and sit down.” Well, I got as far as “Listen, pal, do me a favor,” and Ross poked his finger in my chest and shouted, “I’m not doing you any favors! You will answer my questions!” We have this all on outtakes, by the way. The guy was frantic; it was like his whole life and career depended on getting that piece of film.

What did you do at that point?

Newton: I just kept walking. When my lawyer and I finally got outside and into my car, Ross came at me again and said, “I want to know!” I left with absolutely no idea what all that had been about, but I knew something was up the next day.

Ross tried to see you again?

Newton: No, and that’s why I knew something fishy was going on. You see, there are two parts to a Gaming Commission hearing. The second part consists of going before the commission itself, which can override its board’s decision on whether or not to license an applicant. Naturally enough, when I showed up for that second hearing the next day, I expected more of the same from Ross and NBC. But there was no NBC! Gone! We found out later, through deposition, that Ross and Silverman had left town the night they filmed me and had flown to Burbank to meet with Johnny Carson in his home the next day. They met for over an hour.

Why is that significant?

Newton: Well, as I said earlier, NBC was renegotiating Carson’s contract at the time. Ross and Silverman came after me on a Thursday, and the following Monday the first of a three-part NBC news story about me went on the air. NBC said that I got the money to buy the Aladdin Hotel from the Mafia and that a guy named Frank Piccolo — whom I had never met — had told people he was my hidden partner. I was in shock! Ross obviously had come to Carson City to get footage of me being hostile, and NBC edited it in such a way that they put me on the screen next to this Piccolo guy. Then they went through a whole thing about Guido Penosi getting me the money to buy the Aladdin and how Penosi headed up the entertainment and dope end of the Gambino family. I was devastated! I immediately stated that I was going to file suit. I mean, you can’t imagine the repercussions.

What were they?

Newton: I went from being Mr. Clean to being a hood. I’ve never been involved with drugs or arrested for drunk driving, and to my knowledge, I’d never been around Mafia figures. I’ve worked very hard my entire life to maintain a good reputation, and in three two-and-a-half-minute segments, NBC destroyed it to the point where it can never be restored to its original condition. You think people who saw those broadcasts are ever going to forget them? / don’t. Do you know what it feels like to have parents forbid their kids to play with your daughter because you’re a member of the Mafia? Or to receive fan mail that says, “Jeez, we thought you were okay, but now we realize you’re successful because you’re a member of the Mafia”? It was a nightmare, and a month later it got even worse.

“For years, Johnny Carson used to tell jokes about me on his show, until one day I warned him to cut that shit out.”

In what way?

Newton: I got a subpoena to testify before a federal grand jury in Connecticut. The reason I was there is because one of the NBC broadcasts said I’d lied under oath to the Nevada Gaming Commission about my association with Guido Penosi. I promise I’ll get to him in a minute, but you have to hear what happened next: NBC reported that I was going to be the government’s star witness against the mob. I was sitting at home watching this with my wife, Elaine, and I said, “I’m a dead man.” She asked me why NBC would report such a thing, and I told her I didn’t know, but that I was a dead man.

Who did you think wanted to kill you?

Newton: The mob.

What logical reason would mobsters have for killing you?

Newton: Those were my exact words to an FBI agent just after he told me a mob informant reported that there was a contract out on my life. Mine was one of five names on a hit list. I said, “Why me? I don’t know a fuckin’ thing!” The FBI agent said, “The problem, Mr. Newton, is that they don’t know what you know or don’t know. Their way of doing things is simply to remove any threat.’’

Since you’re still with us, Wayne, did the FBI give you a bum steer?

Newton: Oh no, that hit list was real. About a week before the FBI talked to me, Frank Piccolo — the guy Brian Ross had asked me about — was blown away with a shotgun, and he was one of the five guys on that list. The FBI told me he’d been killed because he was trafficking in drugs, and the particular Mafia family Piccolo belonged to didn’t believe in selling drugs. They felt that what Piccolo was doing by himself would get them into trouble, so they took care of him.

When you learned there was a contract out on your life, what kinds of precautions did you take?

Newton: The FBI asked me if I had my own security people, and when I said yes, one of their agents gave me a bulletproof vest and told me to stay away from my house, because my wife and daughter would be safer that way. The FBI advised me to stay in the hotel, do my shows, and go right back to the hotel room. I did that for a while, and I guess some people finally realized I wasn’t going to be a star witness against the mob, especially since I don’t know anything about the mob.

You do, however, know an underworld figure whom the FBI usually refers to as Guido “Bull” Penosi.

Newton: I said I’d tell you about him and I will. What would you like to know?

For openers, how did you meet him?

Newton: Very simple. In 1963, while I was working at the Frontier Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, I entertained at a lunch given for Jackie Gleason, who was about to leave for New York to start a new television show. Mr. Gleason liked me and asked me to be on his show, so I came East. After I got to New York and did the show, Mr. Gleason felt that if I were working in New York I’d be more available to the show — I think he put me on 12 times during its first year. Anyway, he got me an agent who got me a job singing in the lounge of the Copacabana. Well, one night about eight big guys sat down at a front-row table and one of them waved a $100 bill in front of me. He said, “Hey, kid, sing ‘You’re Nobody ‘Til Somebody Loves You’.” I said okay and sang the song, but I refused to take his money and the guy was shocked. He pulled the same stunt during my second show that night, and again I sang the song he requested, and again I refused his money. The next night the guy came in by himself and sat in a booth, and when I came offstage he sent a waiter to fetch me. When I sat down, the guy asked why I didn’t take his $100. I told him, “Look, I get paid for what I do, which is to sing songs people want to hear. I don’t need your money.” The guy said, “You know, you’re the first entertainer who’s ever refused money from me.”

That guy was Guido Penosi, and that was the extent of the relationship.

How did that relationship change over the next 15 years?

Newton: It didn’t. I didn’t see Guido again for another two or three years, when he came to see my show at the Hotel Fontainebleau in Miami. After that I might have seen him at my shows a total of four or five times — it was just that fleeting. There are fans whose first names you remember, and Guido was one of them. Then, in 1978 or 1979, when I was playing the Desert Inn, I got a call in my dressing room, and my secretary said that a man named Guido wanted to talk to me. I’d only met one Guido in my life and it was him on the phone. He told me about his wife dying and that he wanted to get away and come to Las Vegas, and I said, “Of course, come on. What’s the problem?” And he said, “Well, I have a record.”

Was that the first time you’d heard he’d been in prison?

Newton: Yes, and I said, “So what?” Guido told me that ex-convicts have to register with the sheriff’s department when they come to Las Vegas, so I called the sheriff and told him about it. The next night, people from the sheriff’s department came to me and said, “Okay, what’s this guy’s name?” I said, “Well, his first name’s Guido, but I really don’t know his last name.” The next day, Guido came to Las Vegas and registered, and that’s when I found out that his last name was Penosi. Guido came out to my house for ten minutes and brought my daughter a child’s saddle. And that was the extent of our relationship until I called him for help about a year and a half later.

What kind of help did you ask him for?

Newton: When I tell you this story, you’re going to understand why I’ve spent so much of the last few years wondering what kind of a monster I’ve created. Several years ago, I invested $125,000 in an entertainment tabloid published by a Las Vegas guy named Ron Delpit. About eight months later he and another man came around asking for more money, and when I told them to forget it, they got abusive. I won’t bore you with the details, but it was a bad scene, and I wound up knocking both of them down. Three days after that a couple of guys started calling the dressing room, saying they were going to kill me. I called the police, but I didn’t really take it seriously until a writer from Los Angeles showed up with an unpublished 14-or 15- page article that read like a Dick Tracy story. He’d been sitting in a Los Angeles restaurant and overheard two men in the next booth talking about how four or five guys — led by someone named Dapper — were driving to Las Vegas to bump me off. The guys also said certain phone calls had already been made to me, so I called the police yet another time and asked them to visit Delpit and tell him to cut out the crap, which they did.

Well, the next day someone called up our house and said certain people were going to kidnap my daughter, Erin. The caller then told me what time she left for school every day, who it was that drove her to school, what classroom she was in, and how they were going to cut off parts of her body and send them back to me in a box. That really shook me: They knew far too much. So I called the police again, but I was told there was nothing they could do about it.

Why not?

Newton: According to the police, until somebody actually tries to do something, no crime has been committed. Scary, isn’t it? I was kind of at my wit’s end, and that’s when the beefed-up security first began. I hired bodyguards, and then I thought, “Who do I know in Los Angeles?” I remembered that Guido lived there, and since I knew he’d been in prison, I thought it might be possible he’d know some of these people, so I called him. I told Guido the whole story, and then he got back to me and gave me a telephone number to call. He said, “When the guy answers, just tell him it’s Wayne Newton calling, and then tell him what you’ve told me. I’ll be on the line, and I’ll let you know I’m there.”

The next day, I called the number Guido gave me and a man answered. I said, “Hi, I’m Wayne Newton. Guido asked me to call,” and at that point Guido said, “I’m here, Wayne.” The other man said, “Tell me what happened,” and I did. When I was finished the guy said, “Is that all the information you have?” I said, “That’s it.”

He said, “Okay, one of us will get back to you.” Click.

The death threats stopped. I didn’t hear back from Guido, I didn’t hear back from this other guy. And that was the end of it.

People and Esquire magazines, among others, reported that Penosi may have gotten those death threats stopped, but then made threatening phone calls of his own in order to extort money from you. True?

Newton: No, that was all bullshit. The press came out with that only after NBC said Penosi and this Frank Piccolo were going to be arrested and tried for conspiracy to extort part of my ownership in the Aladdin Hotel.

They were arrested and tried, weren’t they?

Newton: Yeah, and when federal attorneys asked me if I’d testify against Guido I told them, “Look, if you put me on the stand I can only hurt your case, because I’ve got to tell the truth, and I’m known for telling the truth. That man never tried to extort anything from me. He’s never asked me for a cent or a comp or anything. To my knowledge, Guido’s never been anything at all to me but a fan and a friend. I’m not going to stand up and say anything different in court.” At that point I couldn’t publicly discuss the case, and neither could the federal people, so the press almost had to repeat what was being said by NBC. Guido was acquitted, and now it’s a totally different ball game.

This vendetta between you and NBC seems to involve Johnny Carson. Doesn’t it seem a bit odd that he’d be vindictive just because you got ownership of a hotel he wanted?

Newton: Oh, Johnny Carson and I go back a lot farther than that. For years, Carson used to tell jokes about me on his show, until one day I warned him to cut that shit out.

Exactly what happened between the two of you?

Newton: Let me back up a little so that I can put it in perspective for you. Remember I mentioned the job I got singing at the Copacabana in 1963? Well, the late Bobby Dari saw me singing there one night, introduced himself, and become my mentor — and my record producer. It was Bobby’s idea for me to record “Danke Schoen,” and I remember the first time I heard it on the radio. I was in Los Angeles and a disc jockey on KFWB — I still can recall the station — said, “Here’s a brand-new record that’s an absolute smash, and it’s supposedly being sung by a guy named Wayne Newton, but I happen to know it’s Margaret Whiting recording under a different name.” That broke my heart, and I can’t begin to tell you the kind of rejection I then went through at the hands of the entertainment industry. I had the No. 1 hit record in the country, I had Michael Jackson’s voice — I was a boy soprano — but back then, all it brought me was attacks of vitriolic humor. Until Tiny Tim came along, I was the joke of the industry.

What effect did that have on you?

Newton: I was miserable for a lot of years, and I think that out of pure frustration I became terribly heavy — I ate my way up to almost 300 pounds. In those days I was still performing with my brother Jerry, and our act consisted of me singing and Jerry doing fat jokes about me and making cracks about how high my voice was.

Didn’t that bother you?

Newton: I didn’t realize how much it hurt me until I finally started being honest with myself. Fifteen years ago, just after Elaine and I had gotten married, we went to dinner with my manager, Jay Stream, and at some point in the evening he just turned to me and asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I was 26. I told him that I was grown up, and that I was doing what I wanted to do. And he said, “Look, if you want to be an entertainer, don’t you think it’s time you started to look like one? If you want to be a bartender, then quit conning yourself.”

Were you drinking a lot?

Newton: No, but I looked like a bartender or maybe a bouncer — I was six foot three and very heavy. By then I’d been through every motivational speech about losing weight that every fat person has ever heard, but when Jay said that to me, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It was like “okay, enough, I’ve had it.” I decided to straighten out my life in every way. I went home that night, stopped stuffing myself with junk food, and in the next four months I lost 60 pounds and eventually lost 40 more.

Is that when you started taking karate lessons?

Newton: Yes, and I did it because I was angry and hostile. I studied karate every day for three years until I got my black belt, because there was one person I wanted to kill with my bare hands.

Would you tell us who that person was?

Newton: It was my brother.

You wanted to kill your brother? Why?

Newton: I suppose a kind of change was going on, and all brothers are rivals anyway, but before the karate my brother and I would get into fistfights, and he broke my ribs two or three different times. It also seemed that the more okay I became — not the okay-let-me-go-out-and-sing fat kid, but an individual wanting to take control of his own destiny-the more I seemed to be moving in on his territory, and the more we crashed head-on. I think the fist-fights lasted until we finally broke up the act 14 years ago. It’s easier now to look back on that period of my life and say I’m sorry I had to go through all that, but I believe that the preparation and the fire, if you will, that I went through have had a great many more positive than negative effects on me.

Such as?

Newton: To start with, I never knew how much money I made, and it didn’t matter to me because people were taking care of me. Boy, were they taking care of me! When I split up with my brother, I gave him whatever we had — and then I discovered I was $3 million in debt. I found out that of all my earnings I was taking home just 9 percent of what I made. I had business managers putting me into tax shelters that sounded romantic. I owned two oil wells in Oklahoma, and once when I was singing there, I actually went to visit them. One of them turned out to be about 30 feet deep, and the other was just a shallow hole. You see, performers are artists with blinders on; they’d rather sing and dance than worry about money, so they let somebody else take care of their finances. There are an awful lot of people willing to do that for them.

You don’t have a high opinion of entertainers’ business managers?

Newton: There are exceptions to every rule, but I happen to believe that most of them are the leeches of society. I’m not saying “Woe is me,” or “How can all these bad people take advantage of us.” The truth of the matter is that performers tend to live in vacuums of their own making; we’re sitting ducks because we don’t know enough to realize when we’re being helped or when we’re being screwed.

You know the difference now?

Newton: Yes, I do. After I split with my brother and lost all that weight, I think that learning to handle my own money was one of two things that changed my life very quickly.

What was the other?

Newton: I decided I’d had it with being a joke, and that’s when I confronted Johnny Carson. Wherever I went, I used to hear that Carson was telling fag jokes about me. Then one night, about 11 years ago, I was watching his show and during his monologue he said, “I saw Wayne Newton and Liberace together in a pink bathtub. What do you think that meant?” I didn’t find any humor in that, and then I got so incensed that I decided to do something about it.

What did you do?

Newton: I went to see him the next day. I was in Los Angeles, cutting a religious album that afternoon, and all during the recording session Carson’s remark was still bugging me. So I told the record producer to lay the music down on tape, and I’d come back and do the vocals later. I told my manager, Jay, I was going over to Carson’s office, and he said he wanted to come along, so we hopped into my car and went over to the NBC studios in Burbank. It was about three o’clock in the afternoon, and I didn’t call to see if Carson was there, I just went.

What kind of emotional state were you in?

Newton: Cold. When I get angry I tend to be like the calm before the storm, and this thing had been building for a long time. When I walked into Carson’s outer office, his secretary said, “Can I help you?” I said, “No, thank you, I think he can.” I walked right past her and into Carson’s office. Freddy de Cordova, his producer, was in there with him and I’d knawn Freddy through Jack Benny — he’d been Mr. Benny’s friend, and Freddy used to come and see us when we were on tour together. I said to him, “Will you excuse us, please?” — and Freddy was so shocked that he just left.

What was Carson’s reaction?

Newton: He was even more shocked. I remember what I told him almost verbatim. I said, “I am here because I’m going through a personal dilemma in my life. I want to know what child of yours I’ve killed. I want to know what food of yours I’ve taken out of your mouth. I want to know what I’ve done that’s so devastating to you that you persist in doing fag jokes about me.” Carson’s face went white.

What did he say?

Newton: He said, “Well, Wayne, I don’t write these things.” I told him I’d feel better if he did, and he asked me why. I said, “Because at least it would mean that you’re not the puppet I think you are, and that you aren’t just reading some malicious lines written by some writer who crawled out from under a rock. I’m telling you right now: It better fuckin’ stop, or I’ll knock you on your ass.” I get angry all over just thinking about it!

Did Carson get angry as well?

Newton: No. He said, “I promise you, nothing was ever intended in a malicious way. I’ve always been a big fan.” And then he went through all this bullshit about how much he likes me. He just kept talking, and it was obviously a nervous apology — but he never again told Wayne Newton jokes. In fact, I even did his show after that.

That doesn’t sound like it could have been too much fun. Was it?

Newton: No, it wasn’t. When I was on his show and talking to him, Carson would be looking past me at Freddy de Cordova; we had no eye contact at all.

You think you scared him that day in his office?

Newton: In retrospect, I guess I did. And after that, the couple of times I went on his show when he was the host, I felt so uncomfortable that I told my manager I wouldn’t do The Tonight Show anymore unless there was a guest host on. Since then I’ve been on the show when he was gone, by my choice, and I’ve even hosted it a couple of times.

Aside from your infrequent visits to The Tonight Show, you rarely appear on television. Any particular reason why?

Newton: Probably because I’ve never been able to deal with the fact that for TV you really have to perform for the camera. I keep telling myself not to, but if there are four people in a TV audience I’ll perform for them, not for that little red eye. I think high-powered, animated performers like Sammy Davis, Jr., are very difficult to capture on TV because they’re oriented to dealing with audiences. I think the same thing is probably applicable to recordings. I know that when I’m recording I sing differently from the way I sing before an audience.

How so?

Newton: The energy’s different, and so is the motivation. When you record, you are not motivated to reach inside yourself to create performances that work visually as well as vocally. Recording is also much more mechanical than performing for a crowd: After you run through a song or part of a song, your record producer will say, “Wonderful, now let’s do it over.” I don’t like to do that, because I think singing is a little like sex: Once you reach a climax, you’d like to rest before you go again. I just can’t create that moment time after time without it becoming mechanical.

And you’re never mechanical before an audience?

Newton: No, and I think it’s because there must be a basic insecurity within me that keeps making me want to work that much harder and have that audience enjoy me that much more. It could have come from my early years in the business, when I sang in lounges where people could buy a 50-cent drink and sit down, and if they got up and left, you were out of work. Even now, whenever I’m singing, if I see anybody get up to go to the bathroom, I still start to think, “Oh, shit, they’re walking out on me.” I’m really not insecure that way, but for a moment … I guess I am.

You, Frank Sinatra, and Elvis Presley became institutions in Las Vegas — mostly because of the ability to sell out any hotel show — but in watching you work, you seem much more in touch with your audiences than Sinatra is or Elvis was. Do you think that’s the case?

Newton: Well, with Frank, I guess the way to say it is that Frank’s one of those rare human beings who’d rather fail than think he had to kiss anybody’s ass. And I believe that that’s what probably makes it work for him — that arrogance, that ability to kind of say, “Hey, listen, I’m giving, but I’m gonna do it my way.” I think that, in addition to his singing, that’s why people go to see him.

And Elvis? During the last five years of his life, he seemed to almost tune out his audiences.

Newton: I believe you’re correct, but I think that when Elvis first came to Las Vegas, he cared, and it showed in everything he did. But he started to care less and less as his personal life deteriorated, and any time a guy is hurting he does one of two things: He either opens up and tells you about it, or he withdraws and puts up a facade because he doesn’t want anyone to think he’s vulnerable. Elvis did that.

Did you know Presley well?

Newton: Yes, we were good friends, and in addition to that, we truly had professional respect for each other. We used to come to each other’s shows at least once a year, and Elvis would walk out at the start of his show and say, “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Wayne Newton.” I loved Elvis, and we stayed close up until he really started having drug problems. The next-to-last time I ever saw him perform came three years before he died. Watching him that night, I got so depressed that I sat there and cried.

What made you react that way?

Newton: His total deterioration. Total. Elvis probably had been the handsomest man I’d ever seen, but that night he looked like a total bloat. You could barely see his eyes; he must have weighed a good 280 pounds. He phoned in his act that night — he seemed completely indifferent to the audience and didn’t care, or wasn’t able to care, about his work at that point. And then, when I went backstage, he spent more than two hours being concerned about me — what was I doing, was I healthy, was I working too hard? I understood about every third word. When we left, I told my wife I wasn’t ever going to see Elvis perform again.

What made you change your mind about that?

Newton: A call I got from Elvis. The last time he sang in Las Vegas, he telephoned and said, “You haven’t been over, chief,” so I said okay and went to see his show. It turned out to be the saddest thing I’ve ever seen on a stage. It was obvious to me that this was Elvis’s swan song, because practically every song he sang was a way of saying good-bye: “My Way,” “Lord, This Time You Gave Me a Mountain,” “Just a Closer Walk With Thee,” and on and on and on. Anybody who was tuned in had to realize he’d had it. I don’t think Elvis saw anything in his future that would bring him happiness, and I believe the drugs were just a way out. Instead of putting a gun in his mouth, he did it the slow way. His father called me the night Elvis died, and very sobbingly said, “Wayne, I’m so sorry that we kept you away from Elvis the last year or two, because he loved you and you’re one of the people who might have been able to change all this.” I didn’t answer him. It was too late.

Do you ever worry that, like Presley, you also might lose your taste for performing?

Newton: Yes, it concerns me. I find that there are more and more times when I don’t really want to go out there. Once I’m onstage I’m fine, though. I’ve never noticed it when I’m out there.

But some warning lights are starting to flash?

Newton: Yes, definitely. I don’t know if it’s just a phase I’m going through right now. I like to think that’s all it is.

And if it’s not?

Newton: If I don’t feel like performing anymore, I won’t. The whole key for me — at least I hope it is — is my diverse interests. I’m very interested in the business aspect of show business. I’ve started a corporation called Wayne Newton International Resorts, and I envision probably ten major resorts throughout the world. I’m interested in my horses. I breed Arabians, the oldest and only pure-blooded breed of horse in the world. They’re endurance horses and brighter than any other breed, and they’re also the most gorgeous animals you’ve ever laid eyes on. Arabians are simply a work of art.

How many do you have?

Newton: I have 200; there are only about 300,000 registered Arabian horses in the world. I’ve exported and imported Arabians to and from a lot of countries, but the business aspect of it evolved only because of my love for the animals — I ended up with too many horses to care for properly. Even so, my herd’s been valued as one of the top-five herds in the world. I’m also interested in helicopters, and I’m not sure if that will evolve into a business, but I sure like to fly my chopper around the desert. I mean, it’s much more fun than a fixed-wing aircraft. When you fly a helicopter, you’re like a hummingbird and can do any goddamned thing you want. You want to sit it down on top of a mountain, you can. Anyway, I think I have enough interests not to worry about what I’ll do with myself if I should ever decide not to sing anymore.

A few minutes ago, you alluded to the fact that Presley led a very isolated existence. Don’t you think the same thing can be said of you?

Newton: Yeah, and one reason for it can be traced back to those death threats we discussed earlier: They led to other death threats. Sometimes I think every scumbag in the world has thought, “Well, if these other guys could get to him, maybe I can, too.” There have been threats made on my life almost constantly since then, and by now it’s something I’ve almost learned to put up with. And yes, that has caused me to become more isolated than I’d like to be. When I look at people I’ve had tremendous respect for — Presley and Howard Hughes were two of them — I see how isolated those men were. And I see the terrible things that can happen to you as a result of that isolation, regardless of how it comes about or why. I’m convinced there’s a happy medium somewhere, but they didn’t reach it, and I haven’t reached it, either.

How does this affect you?

Newton: Oh, I find it’s having a definite psychological effect on me. I now tend to want to go to fewer places, and it’s something I readily accept. When you first become successful in this industry there’s a certain security you get every time you go out in public — you’re recognized and you enjoy it. But by now it’s to a point where I can’t even go to a restaurant anymore. Last summer I had a business meeting in Atlantic City, and at one point my associates and I walked out on the boardwalk for a total of maybe 30 seconds. The next day, stories appeared in four newspapers — and I got calls from five others — speculating about what I was doing in Atlantic City. And during those 30 seconds, maybe 50 people came up and wanted autographs. Now nobody bothered me in any way, but the fact is you have to be on in those situations, and if you don’t sign 50 autographs, people will walk away thinking you’re an asshole. It’s an untenable position because I don’t want to sign 50 autographs. But getting back to my insecurity again, I don’t want people walking away with the wrong impression, either. And they will if I say I don’t have time to sign my name for them.

So you wind up cloistered?

Newton: Exactly.

That doesn’t sound very healthy.

Newton: All I can tell you is that if I ever get on the road to total self-destruction, I believe there are enough people around me who’ll do something about it. I think people who work for me and care about me wouldn’t worry about their own financial well-being but would instead step up and say, “Wayne, I’m gonna kick you in the ass if you don’t get this straightened out. I’m taking you to a hospital right now.”

You really think they would?

Newton: I sure hope so, but I don’t ever want to put it to a test. Before I get into that kind of spot, believe me, I’ll see it coming and I’ll change what I’m doing. I’ve paid all the dues I intend to pay.

Obviously, this interview took place 40 years ago. Much less obviously, you can still buy tickets to see Wayne Newton perform in Las Vegas this weekend. Smaller venues, certainly, but he still plays the Vegas Strip. In case you’re curious, that is not normal. Mr. Newton even maitains a busy schedule across the country. … There have been television specials and documentaries, even shows just about his house, so you can find a lot more information about him should you be curious. For our part, we’re pretty sure he has portrait in his attic that keeps getting older and older.

OH! And in 1986 Wayne Newton won that lawsuit against NBC. He got an award of $19-million.