The University of Vermont has scored millions in new military contracts. But what’s the true cost to the college’s academic legacy?

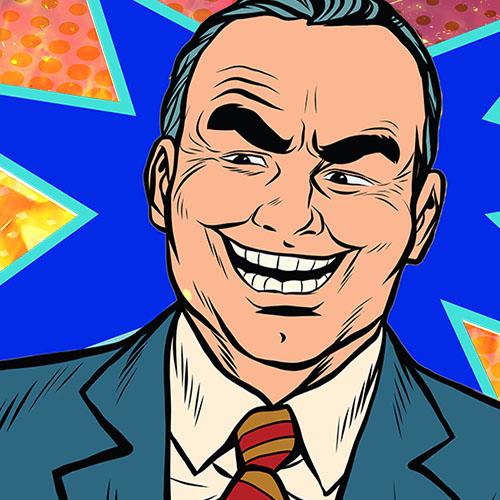

Green Mountain Blues [with Suresh Garimella]

During my college years in Boston, I could reliably cure homesickness by visiting friends at the University of Vermont, where my state’s progressive politics and bohemian way of life were on full display. Suresh Garimella was well into my future.

During my college years in Boston, I could reliably cure homesickness by visiting friends at the University of Vermont, where my state’s progressive politics and bohemian way of life were on full display. Suresh Garimella was well into my future.

I grew up a flower child, the son of artists in a bucolic small town in Vermont’s mystical Northeast Kingdom. Long-haired and in love with nature, I became a peacenik early on during elementary school, when I marshalled my fledgling indignance to inveigh against the government’s War on Terror.

The Green Mountain State has long spawned people like me, as has “Groovy UV,” our largest state school. During visits, I witnessed more than my fair share of drug rugs and kaleidoscopic room tapestries. But homebred students and outsiders alike also shared an affinity for Vermont’s core principles, like pacifism, environmental stewardship and the humanities.

UVM today produces more Peace Corps enlistees than nearly any other school. Some students go on to work as aides for Sen. Bernie Sanders or activists for Bill McKibben’s environmental group, 350.org. Some submerge themselves in Burlington’s idealistic political scene, where local leaders not only allocate funds to fill potholes but argue for divestment of the city’s economy from oil monopolies and the military industrial complex.

When I returned home in 2015 to work as an investigative journalist, I was eager to immerse myself in these values. I soon discovered, however, that Vermont’s crunchy core was being hollowed out, infused with a militaristic sludge, thanks largely to the state’s political leaders — in particular our soon-to-retire senior senator, Patrick Leahy.

In many ways, Leahy fits squarely in line with Vermont’s peacenik attitudes. As a freshman senator, in 1975 he pushed to end military funding for the Vietnam War. Nearly 30 years later, he cast a brave “No” vote on invading Iraq in 2002. One of his namesake programs, the Leahy War Victims Fund, has allocated hundreds of millions of dollars to civilians injured by landmines from the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam. Another, the Leahy law, bans American money from supporting abusive foreign militaries.

And yet from his powerful perch on the Senate Appropriations Committee, much of it as chairman or ranking member of the defense subcommittee, Leahy has stuffed my state, and yours, with billions in Pentagon pork, changing the American landscape in significant ways.

His sustained advocacy for Vermont’s defense industry — not to mention his Irish lineage — has earned him the nickname “Saint Patrick” in the state’s military circles. His major projects include an ICE nerve center operating in the hometown of ice-cream magnate Jerry Greenfield. He’s also funneled tens of millions of dollars to the Vermont National Guard and put his thumb on the scales to bring 20 F-35 fighter jets to the Guard’s air unit in Burlington. (The noisy jets have spurred sustained community opposition — including that of Greenfield’s business partner, Ben Cohen, who was arrested for disorderly conduct during a 2018 protest.)

Leahy has also blessed Norwich University and the Vermont Technical Institute with millions in military grants. UVM is now similarly pivoting to defense research as part of a drastic school reorientation. This new vision is supported by Leahy and his allies, including the school’s president, Suresh Garimella, a military scientist by trade who is boosting defense research while slashing 23 liberal arts programs. This new direction clashes violently with the ideals of John Dewey, a Burlington native, UVM alumnus and pioneering education philosopher who championed a learning model that “keeps itself as far as may be from everything industrial, utilitarian, professional.”

The cozy relationship between higher education and the military state was solidified, ironically enough, by a Vermont congressman named Justin Morrill. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln ratified Morrill’s legislation setting forth America’s land grant universities. In accepting federal funds, these schools agreed to provide mandatory military education. One was UVM, which today oversees the oldest Army ROTC program in the country.

Morrill hoped this requirement would create a decentralized network of citizen-soldiers and thereby discourage the creation of an entrenched military establishment. Instead, the military spent much of the next century consolidating power and influence in many corners of American society, including academia.

Much of this work was spearheaded during and after World War II. That’s when the War Department cultivated in professors what one advisor described as a “consciousness” around their “responsibility to the nation’s security.” The first piece of infrastructure to inculcate this mindset was the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Established in 1941 by President Franklin Roosevelt, it tasked university scientists with developing all sorts of military technology, including the atom bomb.

In 1950, President Harry Truman established the National Science Foundation, a major grant-making apparatus that, from its inception, associated scientific excellence with military supremacy.

In 1961, former President Dwight Eisenhower famously warned about the growing influence of what he deemed the “military industrial complex.” Eisenhower, a five-star general and hero of World War II, had initially wanted to use the term “military industrial academic complex,” but scrapped the language to avoid degrading the positive reputation enjoyed by America’s system of higher education.

His concerns proved prescient. By 2002, almost 350 colleges and universities were conducting Pentagon-funded research. In recent years, no less than $10 billion has been allocated annually for military research. At the same time this money spigot has widened, state support for public education has severely declined.

Vermont has long stood out as one of the stingiest funders of public education. When Garimella arrived at UVM in 2019, he came with an alternative funding playbook he’d perfected as executive vice president for research and partnerships at Purdue University, where he’d secured hundreds of millions of dollars in defense contracts. A brilliant scientist in his own right, Garimella also conducted pathbreaking military research at Purdue around thermal cooling technology.

In his short time at UVM, research funding has hit an all-time high. As part of this work, Garimella forged a partnership with the U.S. Army and upgraded the school’s supercomputer, “Deep Green,” to enable cutting-edge defense research.

During Garimella’s installation ceremony, Leahy hailed his “ability to build ties between our students and Vermont’s economy.” Leahy’s remarks came during a year in which Vermont saw the second largest jump in aerospace and defense growth out of all 50 states, a trend for which the senior senator is largely responsible. During a September conference featuring major military contractors, UVM officials spoke on how their curriculum is creating “your future workforce.”

Months after Garimella snagged the job, UVM established a scholarship program honoring Leahy and his wife, Marcelle. Its major corporate funders included aerospace giant Boeing, which ponied up $1 million. Members of UVM’s board of trustees and associated fundraising foundation have financial ties to the defense industry, as does Garimella. In addition to his UVM salary, Garimella last year made $217,490 as Chair of the Technology Committee of Modine Manufacturing Company, which has secured lucrative contracts to develop thermal management systems for military vehicles.

More military grants seem inevitable for UVM, thanks to these bonds, as well as Garimella’s influential role on the board of the National Science Foundation. Yet a more peaceful curriculum is possible. The state’s leaders must simply give it a chance.

You may of course read the principles and goals of Suresh Garimella for yourself via the UVM official site. For our part, we’d love to do an interview if for no other reason than to ask one burning question: “So, can you describe what the transition was like for you between Ohio State and Berkley?” … He must have had a nervous twitch for weeks. (And now you know why no one ever asks anyone in our department to serve as an investigative journalist. Our business cards would have to say, “Asks Odd Questions and Writes Stuff.”