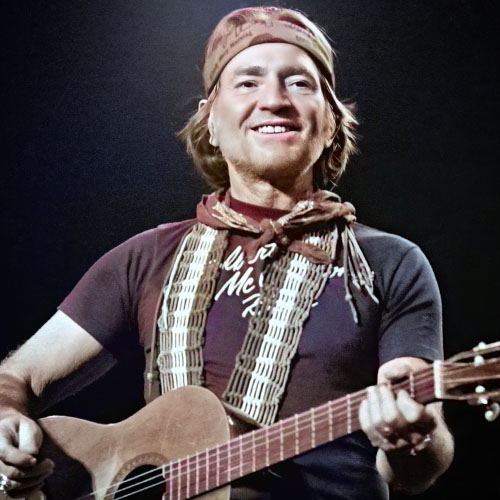

Hollywood’s Biggest Badass Has A Past That Could Rival That Of Any Of His On-Screen Characters

Thank God for Danny Trejo

Danny Trejo is a real-life badass with an adrenaline-fueled past that could rival that of any of his onscreen characters.

The Machete actor, who grew up in Los Angeles, was using heroin at 12, robbing liquor stores and banks with his uncle Gilbert at age 14 and attended his first 12-step meeting at 15. He also spent most of the ’60s in some of America’s most notorious lockups. He even ended up in solitary confinement at Salinas Valley State Prison in Soledad, Calif., after accidentally striking a guard with a rock during a riot. But he avoided landing on death row when the case was dropped.

During his incarceration, Trejo turned his life around, becoming a top boxer and successfully overcoming his drug and alcohol addictions.

After Trejo was sprung, he worked as a youth drug counselor and landed an opportunity to train actor Eric Roberts in boxing for the movie Runaway Train, which led to a small part in the film. Since then, the Mexican-American star has become a Hollywood staple and is one of the most prolific actors in the biz, amassing a cinematic rap sheet of over 400 acting credits.

Now 77, Trejo has been sober for 52 years, and since cleaning up his act, he’s devoted his life to helping others. Ahead of the release of his tell-all Trejo, he spoke with Penthouse about how he rebuilt his life after finding sobriety and spirituality, his life-changing acting roles and how he overcame adversity to become Hollywood’s friendliest bad guy.

When’s the last time you read a Penthouse magazine, Danny?

To be honest, I haven’t read anything but scripts for the past two years! I’ve been busy, busy, busy. I tried out for the Penthouse centerfold, but they wouldn’t take me.

Ha! Congratulations on your memoir, Trejo. The book reads like a very honest and raw portrait of your life.

When I started writing it, I was just kind of scribbling stuff down. Then a friend of mine, Donal Logue, an actor who was on Gotham and Sons of Anarchy, actually started reading it and told me I was skipping over stuff. He started helping me, and we both wrote it together. I started reliving a lot of stuff that I’d kind of put out of my head. It was awesome because I was writing with somebody I really trust. Donal and I have been friends for years; he’s my BFF. So, it was real, and it was simple because of the trust we have. It was kind of like working with a really close brother who knows everything about you.

You attended your first 12-step meeting when you were just 15 years old. Do you remember anything from that first meeting?

[Laughs] Absolutely. I walked into that meeting holding a case of beer, three bottles of wine and a half-pint of whiskey, and I had a .38 snubnose in my pocket. I didn’t know it was an AA meeting. We went in thinking it was a party! There were a lot of cars parked outside, and to me that meant some kind of function, so we crashed in through the front door and saw a big sign that said, “We care.”

It was strange, but I was already loaded on pills. The man running the meeting invited me to stay and started to explain the program to me. Then he whispered the curse.

What was the curse?

He said, “If you leave, you’ll either die, go insane, or go to jail.”

And it seemed like every time I would get in some kind of trouble, I would hear that, you know? Die, go insane, or go to jail, and that’s the curse of the 12-step program.

How have you managed to stay sober for more than 50 years, especially with the temptations that can come with working in the film industry?

I no longer want to shower with 50 men. I no longer want to stay in isolation for six months, you know? Some of us, we die, go insane, or go to jail. Insanity is doing the same thing but expecting different results. The results to me, of doing the same thing or falling into old habits, is going to jail. That means I have to shower with 50 men again and try not to look, and here I am again, locked up, sitting in a hole. I guess the temptation for me is not what it is to everybody else. When I hear everybody else talk about it, it seems like they had a lot of fun when they were drinking and doing drugs. Whereas for me, I got shot at, got stabbed, people tried to chase me, I had the police after me. So, it might have been exciting, but I wouldn’t call it a lot of fun.

Even through your darkest moments in the book, you continue to crack jokes and remain positive. Would you say laughter and humor play a part in your recovery and approach to life?

It’s funny that you say that because I always used to sing “Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, zip-a-dee-ay!” in the morning in prison to keep my mind going. I’d sing “Get rid of worry in a hurry, chase the blues away! Just laugh and be happy!”

Well, when you’re doing that, it’s kind of hard to feel down! I’ve had people call me and tell me they’re depressed, and I’m like, “OK, let’s try this.” And I’ll sing to them, and they’ll start laughing. To me, it’s just another form of prayer and meditation because it is just putting your mind in a different place, instead of concentrating on being depressed. I’m singing this silly-ass song, and I’m laughing.

Would you say that your relationship with God played a role in your sobriety, too?

Absolutely. Without God, I’d be dead. I made a deal with God in 1968 in the hole in Soledad. I said, “If you let me die with dignity, I’ll say your name every day, and I will do whatever I can for my fellow inmate.”

I was in prison, and I didn’t think I was ever getting out. I honestly believe that God said, “OK, sucker, I’ll give you a break. You got the rest of your life to prove it,” and I’ve been living up to my deal ever since. Because it wasn’t help me pass this test or let me get a good grade or don’t let my mom be mad at me. I just wanted to die with dignity, and he’s been keeping his deal, and I’ve been keeping mine, and you know, it’s been a pretty good life.

You’ve dedicated the majority of your life to helping others achieve recovery. Why does this work remain important to you?

Well, I honestly believe that’s the way we’re supposed to live. When I see people talking about how spiritual they are and stuff, I always wonder: How many people have you helped today? How many homeless people have you fed? How many pairs of socks did you hand out? Because everybody who I consider a friend, and everybody who I would break bread with, has thermal underwear, socks or a bag of hamburgers in the trunk of their car because they’re passing them out to homeless people or they’re helping kids in juvenile hall. That’s what we do. That’s what makes people feel good. Not just them, but the person that’s doing it. I like feeling good, and that makes me feel good.

When I see people talking about how spiritual they are and stuff, I always wonder: How many people have you helped today?

Recently, I bought a bunch of food, and I was handing out meals to the homeless. That’s important, especially right now, after this pandemic. There are people homeless, and not because they want to be. They’ve lost their apartments. They’ve lost their houses. This was a worldwide epidemic, and now we have to get back from that. So we’ve got people who were kind of bombed out. Like in London when people were bombed out, during the Second World War. We didn’t say, “Oh well, they should just pull themselves up now.”

We took care of them. And that’s what we have to do now. We have to take care of all these people. I’m no saint, but I just know we’ve got to do our part.

For someone who is struggling today, what advice would you give them?

Go do something for somebody. Just do something, anything. Go to your closet, find some old shirts or some clothes and just go hand them to a homeless guy. When you see the joy that one of your old damp shirts can bring someone, you can’t help but feel good. When the people I sponsor call me and say, “You know, this is happening, and I feel so bad.” I’m like, all right, come on, let’s go feed some homeless people.”

One day I gave a 20-dollar bill to this lady on the street who was selling these little thread bracelets. She had her two little kids with her, and she was making these bracelets on a blanket. So I took two of them, and I gave her a 20. She was like, “I don’t have change.”

I insisted, but she was scared to take it. She was homeless, and she kept saying, “Oh no, no, no, I don’t have change.”

And I was like, “That’s OK. I have these two bracelets. I don’t need change.”

And she was overwhelmed and said, “Oh my God, I can get some shoes for my kids!”

Shoes? Damn, where you shopping? I want to know where you’re shopping! But she was so grateful and so overwhelmed. I was going through a divorce, and I felt like a million dollars. There’s always somebody that needs help. All I’ve got to do when I feel bad is find somebody who feels worse and help them.

In the book, you’re very honest about how your view of women and your behavior toward women has changed throughout your life. Would you say your daughter Danielle played a role in that shift?

[Laughs] She did. My daughter has absolutely everything to do with it. Let me tell you something, because if I would say something like, not derogatory, but smart, kind of like, “Hey, ese … I love the way that skirt fits you,” or a guy kind of comment, she’d almost slap me and go, “Dad! You can’t do that. My God, what is wrong with you? What if somebody said that to me?”

And she started doing that when she was like five and six, you know? My daughter has had everything in the world to do with my changed attitude toward everybody. She’s an amazing little girl. Well, she’s not little. She’s 32 now, but she’s just amazing.

Could you ever have imagined while in prison, that 50 or so years later you would be where you are?

When I made my promise, when I made my deal with God, I didn’t even say I will help people every day. I remember saying, “I’ll say your name every day, and I will do what I can for my fellow inmate the rest of my life.”

I thought I was going to stay in prison. I didn’t even think about getting out of prison. And when I got out, it was like, wow, OK, God. So, everything that has happened since that time, I blame on God, because I never thought I was getting out of prison, let alone would be where I’m at. I have to say that if you don’t like the way I am, blame God, because I’ve just been trying to live the way he wanted to me live. It’s how he wants all of us to live. Not just me. It’s funny, though, because everybody that I deal with ends up being involved in helping people. My ex-wife Joanne belonged to this organization that gave me a humanitarian award, and we’ve been divorced for 30 years, but when I got the award, she told people, “Danny showed me how to care for people.”

She said, “I would wake up there would be some drug addicts sleeping in my living room.”

And I would say, “Oh, he needs a place to stay. We’re going to help him,” because that’s what I do, and that’s what I did. So that was the best compliment I could get—and that’s coming from an ex-wife!

The film “Runaway Train” gave you your big break, and it was also a turning point for you in your life.

Eddie Bunker. You’ve got to mention Eddie Bunker. I was in San Quentin with him, and this is a guy that when he saw me on the set of Runaway Train [as an extra], he remembered that I won the lightweight and the welterweight championships [in prison]. He saw me win that. And he goes, “Trejo, are you still boxing?”

And I said, “No, man, I’m 40 years old. Are you kidding? I don’t want to get hit in the face no more.”

And he said, “We need somebody to train one of the actors how to box.”

And I remember saying, “What’s it pay?” because at the time they were giving me $50 for being an extra.

When he told me the pay was $320 a day, I said, “How bad do you want this guy beat up?” Because I was making $320 a week as a drug counselor.

And so Eddie kind of steered me toward training Eric Roberts how to box for Runaway Train. That’s how I got into the movie business.

What’s your favorite role or coolest film you’ve worked on?

My son Gilbert just finished directing me in a music video for a band called Starcrawler, and I think that was one of the highlights of my life. He would give me a direction, and under my breath I would tell him, “I used to put you in time out,” and he would say, “Yeah, but I’m the director now, Dad.”

To me, there’s God, then there’s the director. On a film set, I’m hired to act and he’s hired to direct, so I had to give my son the same respect that I’d give Michael Mann or Robert Rodriguez. It was unbelievable. There were a couple of times I almost started crying, because, wow, here he is, my son Gilbert Trejo directing me.

Have you ever struggled with feeling respected in Hollywood?

I think people have struggled with not giving me respect in Hollywood. I respect everybody. I would rather have a mangy dog for a friend than an enemy. I think it’s up to an individual to demand respect and to tell people when they’re being disrespectful. I won’t let people disrespect me. There’s a couple of times I’ve threatened to beat people to death for disrespecting me. Movie stars are dicks. Not all of them … yeah, all of them. Hollywood is geared to seduce you into thinking that everybody’s supposed to go get you a cappuccino. It’s made that way, and the reality is that a movie is a great big team effort. Piss off the camera guy, see what happens. Your kids will be asking you, “Daddy, why are you blurry in this movie?”

I try to treat everybody the way I want to be treated. And it seems to work for me.

In fact, Eddie Bunker once said the secret to my success is that everybody who’s worked with me wants to work with me again. I sound like I’m bragging, but I want to leave every situation that I’m in better than when I got there. Whatever the situation is. Eddie was awesome. He passed away but remains one of the greatest, greatest crime writers ever. Another thing he said to me was, “The whole world can think you’re a movie star, but you can’t,” and I said, “What are you talking about?” and he said, “Watch, come here.” So we went over to one of the stars who was on this movie that we were on. We were standing there, and everybody was like, you know, sucking up to him. And then when he walked away, we heard people saying, “Boy, I’d like to kick that guy’s face in!” Woah! They’ll be nice to you because you’re the star, but if you’re not a good person, when you leave, they won’t ask you back.

Clearly, you’re doing something right because you have over 400 acting credits to your name.

Yeah, I’ve done a lot! I have to admit a lot of those films that I’ve done were student films, where I did them as a favor for some kid who was a first-time director. Low budget films, where they’ll buy you lunch or something. People think that since I’ve done so many movies I must be a millionaire, but the reality is that a lot of those films were favors. In fact, I just got asked to do another favor. Some kid is doing a film, and he’s a student. Yeah, OK. I’ll do a walkthrough or something. I don’t mind! I think that’s one of the reasons why I’m successful in the film industry.

You say in your book that you use your film career as a vessel to amplify a message to a wider audience. What does that mean for you?

When I speak at schools and juvenile halls, I find the first thing you have to do is get the kids’ attention. Number two is that’s impossible because they have none; they have no attention. And three, you have to show them you’re cool. And if you’re 10 years older than them, you’ve lost your cool badge. Then you have to deliver your message. My message is that alcohol and drugs will ruin your life. Education is the key to anything you want to do, and anybody can deliver that message.

The only problem is because of number one they’re not listening. Well, the blessing that this movie career has given me is that I have everybody’s attention the minute I get close to that campus. Teachers have told me the kids that don’t even come to assemblies are there. I went to some of the worst schools in Los Angeles and going into an auditorium, the kids are screaming and yelling, and the teachers are screaming and yelling back. I walk out, and everyone goes quiet. That’s not because of Danny Trejo, though. That’s because they’re seeing the guy from Heat, the guy from Desperado, the guy from Con Air, the guy from Machete. They’re seeing the guy from all those movies that those kids love, and suddenly, boom! They want to hear what that guy has to say. So, it’s a blessing. I’m still doing this work. And that’s what this movie business was about for me.

You’re also the record holder for most onscreen deaths, having been killed in 65 films at the time of this interview. What’s been the most memorable one?

I think it would have to be in the movie Heat with Robert De Niro. I think that was the most unreal, just being on the screen by myself with Robert De Niro. It was like, whoa! That was the biggest thing, because Robert De Niro was like the president, you know what I mean? He’s like the main guy, and working with him felt like being knighted. I felt like Sir Trejo! And he was a real gentleman, who was so professional and just so unbelievable. When he said, “How do you want to do this death?” I almost pissed my pants because, wow, it’s Robert De Niro. I’ll never forget that as long as I live. And then he came and did Machete with me.

You also have developed an empire of businesses, including Trejo’s Tacos and Trejo’s Coffee & Donuts in California. What made you decide to branch into hospitality?

Everything good that has happened to me has happened as a direct result of helping someone else. There was a director who wanted me to do this low budget movie, but I’d had an offer for a bigger movie that offered more money. But my agent, Gloria, said I should do the low budget one because it looked like a good deal. So I did this low budget movie that I didn’t want to do, even though at that time I would have preferred the money. The movie was called Bad Ass. It turned into a trilogy, and I ended up making four times the money.

Everything good that has happened to me has happened as a direct result of helping someone else.

Gloria won’t let me forget it. This is where I met a producer named Ash Shah, who saw that I eat good quality food. I don’t eat processed or fast food. And all of a sudden, he said, “Hey, why don’t you open a restaurant?”

Jokingly, I said, “Trejos Tacos!” Because my mom always talked about opening a restaurant just to piss off my dad.

And that’s actually how I got into the restaurant business. Ash brought me a business plan. I gave it to Gloria, and the rest is history.

From your film career, to your work as a recovery advocate, to becoming a restauranteur, you’re constantly reinventing yourself. How do you have so much energy for so many diverse projects? Any plans to slow down?

Yeah, when I die! No, I also just started a record label. Chicano Soul Shop Vol. 1 is out now, and we’re getting ready to drop an album called Trejo’s Soul Classics. I was helping this little lady whose daughter wanted to be a singer, so I started this record company. And I’ve got three or five artists right now that are all signing with me, and we’re getting ready to drop another album. I like watching people be successful.

In the book, you said when you were diagnosed with cancer, you were less concerned about dying and more concerned about directors finding out and you losing work. Why is that?

Basically I had these contracts that were already signed. And it was like, if the studios find out that I have cancer, I could lose it all. And I didn’t want that. So I went to work, while in the middle of chemo. God, I went to work feeling like I was dying. I remember this one movie, every time the director went “Cut!” I would walk off set by myself and throw up and then come back. Simply because we were shooting, and I didn’t want to cost everybody money. And also, I got bills like everybody else. I was like, I don’t want to leave my kids with this debt. I didn’t want to leave owing a bunch of stuff.

You also do animal rescue work. Why is animal advocacy important to you?

Let me tell you something. Dogs are our responsibility now. Way back when they were wolves, we called them into our fire. We domesticated them. They were fine just crapping anywhere they wanted and just doing whatever they wanted. They were fine. But we brought them into our fire, and we domesticated them. We turned them into Shih Tzus and everything else. So they’re our responsibility. So every time you pass an animal shelter and you see dogs there, you’re not living up to your responsibility. I love dogs. I’ve got five or six. I’m trying to live up to my responsibility—and that’s animals and kids. Right now, we got a bunch of kids living in Long Beach Civic Center, and they came from Mexico, and they’re our responsibility. Some people say, “Well, they’re illegal immigrants!” But it’s not about that. They’re human beings, you know? I feel that we’re responsible for everybody in the world. That’s just the way it is.

It’s pretty clear the world needs more Danny Trejos.

[Laughs] Wow, say that in the article and tell my three ex-wives they need to remember that!

In a rare circumstance come to life, you can also read a different interview with Danny Trejo pubished in Penthouse over a decade ago now. Someone that stays interesting enough to devote precious print space to twice do not come along very often.

Also, Trejo: My Life of Crime, Redemption, and Hollywood (Atria Books, $27) hit bookstores July 6th of this year, and of course you can find it at Amazon. Although we both enjoy and encourage reading, we do rather enjoy eating as well, so you might check to see if you can find a Trejo’s Tacos near you. Or if you happen to be bopping about Hollywood at some point, put Trejo’s Coffee and Donuts on your list. Grab a Margarita donut, pair it with De Berry Bomb, then stroll down Santa Monica Boulevard singing “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” along the way. Disney may have run away from it, but people will still smile at you.