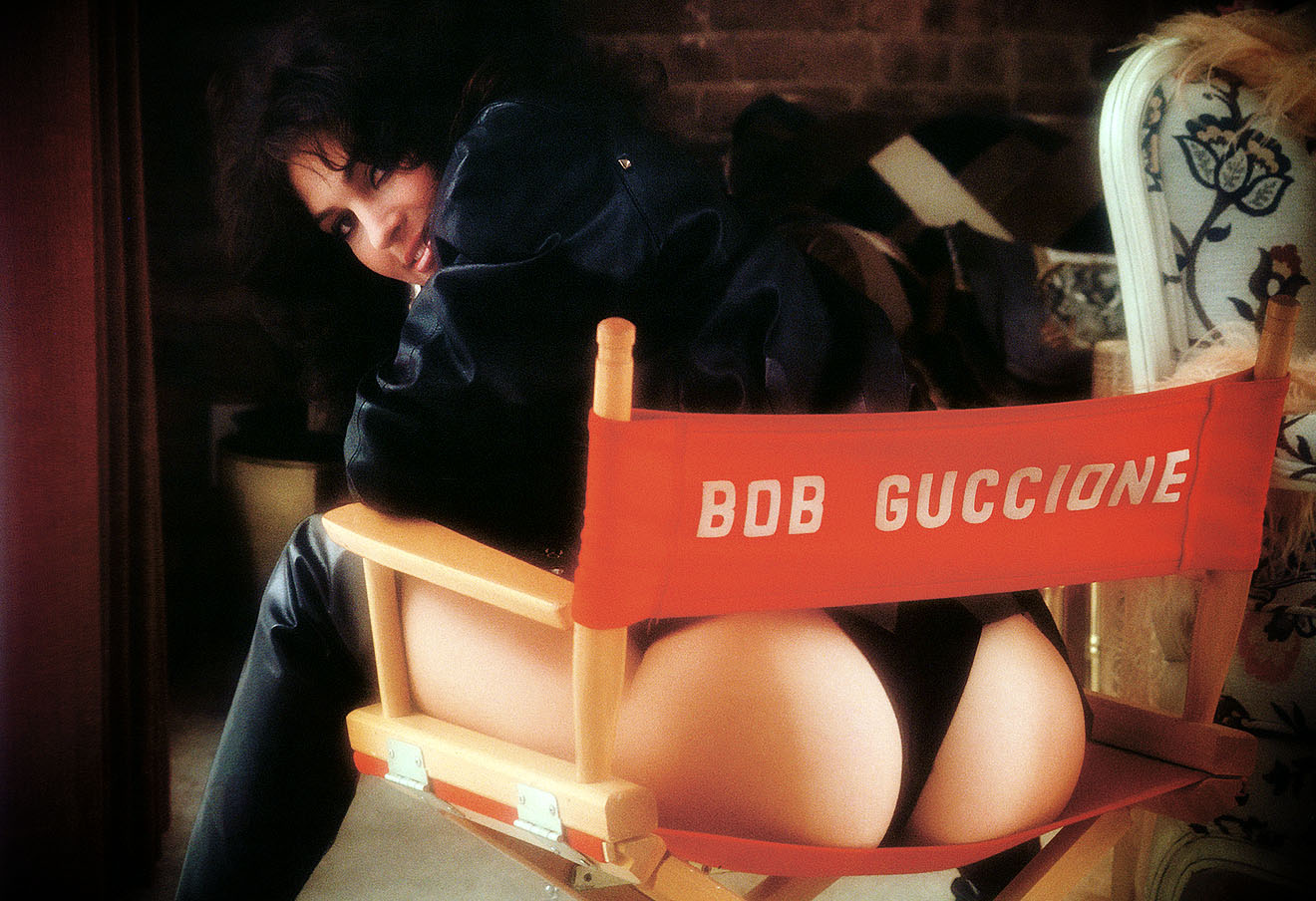

Penthouse founder Bob Guccione Sr. was eccentric, iconoclastic and outlandish. Of course we admire that in people, so we loved him. Quirky and head-strong hits pretty much on brand around here.

The Man Behind the Brand: Bob Guccione Sr.

This past July, what can only be described as an extraordinary media event occurred. It pushed the Olympics, together with the momentous news of Geraldine Ferraro’s nomination — the historic selection of the first woman vice-presidential candidate — off the front page of just about every newspaper in America. And radio and television news were dominated for more than a week by the ever-changing complexion of the same media event.

The event, reduced to its basics, was the forced resignation of Miss Vanessa Williams as Miss America of 1984. “I am not a person who gives up,” said the titleholder, giving up her crown for what was described as the “higher interests” of the Miss America Pageant.

But there was much more at work here than this ringing concession to the public relations requirements of a basically commercial beauty contest. One year before winning the pageant (and having become the first black woman to do so), Miss Williams had not only posed nude for a Mount Kisco, New York, photographer, but repeated the event in even more bizarre style one month later for yet another photographer. (Those latter pictures are the subject of this month’s all-new Vanessa pictorial.) The first set of pictures, which included sexually explicit lesbian poses, appeared in Penthouse’s September 1984 15th Anniversary Issue, coincidentally the last month of Miss Williams’s reign as Miss America.

The discovery that Penthouse magazine was about to publish the controversial portfolio led to pressure by the pageant on Williams to resign. And that resignation immediately set off a chain of national and international morality debates that seemed to divide a good portion of the world’s population into two factions: those who agreed with the Penthouse decision to publish the pictures, and those who did not. Indeed, the controversy rages to this day, in terms of furious and still-expanding arguments that involve a whole range of philosophical questions: Was it right for the Miss America Pageant officials to pressure Williams to resign? Was Penthouse right to publish the pictures? Was there really anything wrong with Williams posing nude? Who was exploiting whom? (And to further complicate matters, questions of convoluted, racially inspired conspiracy scenarios were raised, not so much to explain the sequence of events but to milk the story for all it was worth.)

Interestingly, the central figure in this controversy is not Vanessa Williams, but the man who secured the pictures and later made the decision to publish them, Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione Sr. From his New York headquarters, Guccione has watched the national debate somewhat bemusedly — an attitude occasioned by a good deal of sanctimonious claptrap from many of the characters involved. For example, Miss America Pageant director Albert A. Marks, Jr., Guccione’s severest critic, reached new heights of oratorical self-righteousness when he described the Williams pictures this way: ’’As a man, a father, a grandfather, as a human being, I have never seen anything like these photographs …. I can’t even show them to my wife.” (And Venus Ramey, Miss America of 1944, pronounced Miss Williams a “slut.”)

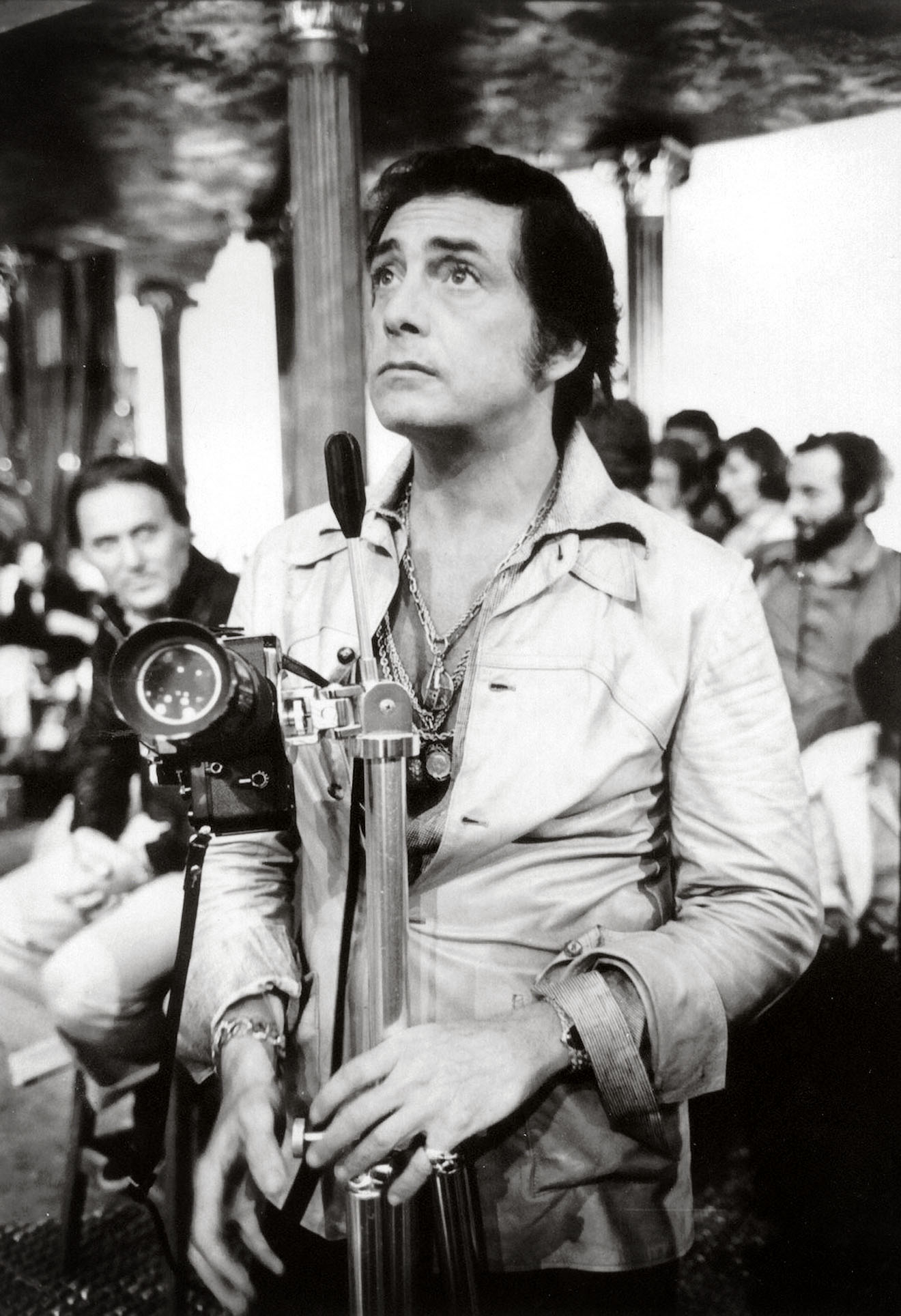

Guccione, of course, is no stranger to controversy. Ever since he began publishing Penthouse in England in 1965 — and four years later brought it into the United States, not to mention its eight subsequent foreign editions — the magazine has probably become the most controversial publication of our time. Its reputation is composed of equal parts of no-holds-barred investigative reporting and writing and controversial political cartoons, along with its famous ground-breaking photography, a reputation that often alternately enrages or stirs a worldwide audience of every possible color and stripe. Whatever the reaction, very few people are indifferent to Penthouse. (The magazine’s September issue sold a record 6,000,000 copies, and became the all-time hottest item in publishing history. Copies were being sold for $30 each by the third day of sale, and some enterprising entrepreneurs were charging anywhere from two to seven dollars for a brief look at the Williams photo layout.)

As the creative spirit behind the magazine, Guccione is usually the focus of the assorted controversies that it consistently manages to stir. And so it was with the Vanessa Williams imbroglio; Guccione’s decision to publish the pictures represented at once his conviction of what was newsworthy, and at the same time his philosophy that such institutions as the Miss America Pageant represent a fundamental form of hypocrisy.

Not everyone agrees with Guccione, but his decision on the Williams pictures offers important clues to the thinking of a man often described as the catalyst for the modern sexual revolution. To get some insight into the figure most central to the controversy, Penthouse engaged an outside, unaffiliated journalist to probe Guccione’s views on the Williams matter — and some of the related implications. The conversations, which took place in Guccione’s New York townhouse, centered on why he made the decision, and why he still thinks he was absolutely right.

Mr. Guccione, you are a very controversial man. Many people view you as something less than a public benefactor. Do you go out of your way to encourage controversy?

Guccione: I’m outspoken. I have strong convictions and I’m a bad loser … I’m also highly visible in a very volatile industry … one that causes hair to grow on the palms of pubescent schoolboys. That makes me an easy, if not reliable, target for the press.

Why reliable?

Guccione: Because every season is open season on sex. There’s an old political adage: When in doubt, attack sex. It always works; always doubles the audience, always fine-tunes the attention.

And always controversial.

Guccione: Always!

And wouldn’t it be wise of you to encourage this kind of controversy? Doesn’t high visibility of this sort sell magazines?

Guccione: Indeed it does.

You agree?

Guccione: Only that it sells magazines. I do not agree, if I read you correctly, that I court controversy as a method of selling more magazines. That simply isn’t true. If, on the other hand, I am controversial, it just means that I’m being true to myself.

What do you mean, “true to myself”? That would presuppose that you are controversial by nature.

Guccione: Not at all! It just means that I’m being myself. I’m not trying to be anyone else; I’m not conforming to any special image. I’m being me and I’m doing things my own way.

Wasn’t this whole Miss America thing just a well-timed stunt, a publicity gimmick to sell more magazines?

Guccione: That’s a bit of an oversimplification, but let me put it this way. The answer to part one of your two-part question is, No, it was much more than a stunt. It was a legitimate scoop and a super news story. I can’t imagine any editor turning it down. As to the second part of your question, What the hell am I in business for if it’s not to sell more magazines? Of course I bought the Vanessa Williams pictures to help sell magazines. Every single feature in the magazine is either created or bought with that purpose in mind. She just happened to pack more publicity value than most.

What makes nude pictures of Miss America so newsworthy?

Guccione: The public’s basic distaste for hypocrisy, their love for scandal … for punching holes in the establishment, their hatred of liars, their sanctimony, and their own implacable sense of guilt.

Do you really believe that a story as thin as this deserved the kind of attention it received in the press?

Guccione: It’s not for me to say! The attention any story gets in the press is really a factor of the public’s interest and not that of the media. If a story sells, it’s only because the public is buying.

So you’re really saying the public is no better, or no less guilty, than the media it supports?

Guccione: Something like that.

What about the press that openly resented your publication of the Vanessa Williams pictures — the magazines and newspapers that campaigned against your claims of newsworthiness and “having an obligation to your readers,” etc., etc.?

Guccione: Sour grapes!

Why sour grapes?

Guccione: Because if they had uncovered the story they would have printed it just as quickly. They couldn’t have published the pictures, of course, being newspapers or other so-called family-oriented publications, but they would have treated the story in a much more insidious and sanctimonious way. The press, by its very nature, has a particularly vile and lip-smacking approach to human indiscretion. They thrive on bad news as if human fallibility, scandal, and bad luck were commodities of preference and priority.

You seem unusually bitter.

Guccione: Not bitter … just disappointed.

How do you feel the press treated you throughout the Vanessa affair?

Guccione: Insincerely self-consciously. Like the judge whose personal prejudices override any fair hearing of the evidence, they jumped to conclusions that were invariably erroneous and unfair. Not all of the press, mind you, but most of it.

Why unfair?

Guccione: Well, they painted me and Tom Chiapel, the photographer, as if we had done something genuinely evil and unAmerican. As if we had manufactured the pictures … almost without her knowledge. As if she had never taken them, or at least, not willingly. And the pageant — they treated the pageant as if it were an all-American institution bristling with real ideals and national pride. You would have thought we had desecrated the Lincoln Memorial.

Didn’t you, in a sense, destroy something very American and very traditional?

Guccione: Of course not. The Miss America Pageant is really a commercial enterprise; a business proficient in the exploitation of women for profit; an organization created 63 years ago to promote business in Atlantic City. All we did was puncture a very pompous balloon. The pageant was failing, its Nielsen ratings were on the decline, and the whole lumbering affair was out of sync with reality.

Why out of sync?

Guccione: Because social tastes, attitudes, and mores have changed, progressed, matured, while the morality of the pageant, its image of the untouchable and asexual girl next door, its whole philosophy of “look, don’t touch!” have not changed. The mystique of the perennial vestal virgin is unrealistic and, perhaps worse, uninteresting. The public at large doesn’t care anymore. They’d rather watch “60 Minutes” or “Saturday Night Live.”

Are you suggesting that the pageant, rather than Penthouse, was in the wrong?

Guccione: If anyone was in the wrong, yes!

How do you figure that?

Guccione: Because they acted in a very high-handed and arbitrary way. They fired Vanessa, we didn’t!

I don’t think you gave them much of an alternative.

Guccione: They had the best possible alternative. All they had to say was, “During her reign, Vanessa Williams conducted herself in a proper and commendable way. That is our business; beyond that, we do not pretend to control the lives of our contestants either before or after their relationship with the pageant.” The public would have loved them and the pageant would have landed right-side-up with both feet squarely planted in the twentieth century. As it happened, public opinion ran heavily in her favor and very much against the pageant for firing her. It was a dumb move and Albert A. Marks, Jr. didn’t win any brownie points making it.

A moment ago, you referred to the Miss America Pageant as a business “proficient in the exploitation of women for profit.” Isn’t that an equally appropriate definition of Penthouse?

Guccione: Not really. Penthouse offers a variety of entertainment and information. Not just girls. Sex may form a principal focal point of our editorial profile, but that’s no more than it does in real life. By comparison, the pageant is one-dimensional. And our girls are different … they’re real. They may live next door in the traditional, folksy sense, but they’re sexually alive and responsive and they make love just as eagerly as you and I.

Is the fact that they’re sexually more active, or more visibly active, to their credit and yours?

Guccione: Let’s put it this way. The fact that they’re not ashamed of their sexuality, that they treat sex naturally and openly, is very much to their credit … and ours.

Do you feel that by encouraging a sexually freer and more permissive society that you’re performing some kind of public service?

Guccione: Providing you’re not confusing the term permissive for promiscuous, the answer is yes! ’If we can encourage society to take a more liberal view of itself, to understand the incredibly complex and wondrous mechanism that drives it, then I would say we did something genuinely important and constructive.

On one hand, you talk about the liberalizing and beneficial effects of Penthouse — about women whose open sexuality would set an example for us all — and on the other, you take a real woman like Vanessa Williams and punish her publicly for participating in the same sexual adventures you praise in others.

Guccione: I didn’t punish Vanessa Williams, I published her! I did precisely what she wanted me to do — me, or anyone else. I published the pictures she posed for. That’s why she signed a model release, because she wanted to see her pictures published! Surely that makes sense. That’s the only reason people sign model releases.

Your personal philosophy apart, what about the girl herself? You knew the story would destroy her career. Didn’t you consider any of the moral, not to mention human, implications of such a move, and now, having gone through with it, do you feel any remorse whatsoever?

Guccione: Firstly, looking after her career is her business and not mine. My business is publishing magazines and providing a service to my readers. My first obligation is to them. Everything else, especially the Miss America Pageant and Vanessa Williams, comes second. Number two, what career did these photographs destroy? Miss America? Two more months and she would have passed into oblivion, like just about every other titlist before her. Instead, she has become the most famous Miss America that ever lived — not only here but throughout the world. I cannot believe that there was a newspaper anywhere that didn’t carry the story.

And you feel no remorse at all …?

Guccione: Not now. I did in the beginning. I didn’t know the story would blow as big as it did and I didn’t think the pageant would fire her. The moment I saw the way things were going, I got in touch with her lawyers and offered to help. I said that if she lost her job with the pageant we would hire her to do precisely the same work for us that she was doing for them at twice the price — namely, $250,000 per annum. No more photographs, just traveling around the country, promoting the magazine, meeting the press, appearing on radio and television, representing advertisers, etc., etc. I also offered, assuming she lost her crown, to fully finance any action she cared to bring against the pageant by way of seeking damages and/or the reinstatement of her title. Her lawyers said they would consider it. Twenty-four hours later they called back and rejected both offers. We certainly tried, and with her cooperation we might even have won. The fact that she posed for nude pictures is no big deal. Hedy Lamarr did the same thing; so did Sophia Loren, Jean Harlow, Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot, etc., etc. The list goes on forever. Today, some of the most successful and prestigious actresses in the world are appearing in all kinds of sexually explicit scenes — not only in films, but in men’s magazines as well — and for reasons that have nothing to do with business. They don’t need the notoriety it attracts and they don’t need the money.

You said, “for reasons that have nothing to do with business.” What kind of reasons?

Guccione: Ego! I’m sure Joan Collins’s appearance in Playboy wasn’t intended to further her career. And I’m sure she didn’t do it for the relatively small amount of money they paid her. She did it because she’s getting older and she wants the world to know that she’s still a beautiful and desirable woman. You can’t fault her for that. And when Pia Zadora, who is married to one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in America, agreed to let me photograph her for Penthouse, it was for personal reasons, not monetary, and not because she needed the publicity.

Why, in your opinion, did Vanessa do it?

Guccione: Vanessa’s reasons were more traditional. Like most young, pretty girls who want to break into modeling or motion pictures, a magazine like Penthouse offers all kinds of marvelous advantages. In one fell swoop, everybody who is anybody in the entertainment business will get to see her, all of her, in the most flattering possible manner. Nineteen pages of color in the world’s top-selling magazine for men is nothing to sneeze at. In my opinion, that’s what Vanessa wanted! She wanted to break into modeling and she doubtless saw men’s magazines as the most exciting and expedient way of getting there.

She, on the other hand, says that she agreed to the pictures because she thought they would be silhouetted. She also said that they were intended for her own personal use.

Guccione: In that case, why did she sign a model release?

There seems to be some dispute about that. To this day, she continues to maintain that she never signed the Tom Chiapel release.

Guccione: In that case, let me assure you that she’s lying. Whatever her reasons, she’s lying, and I have the release to prove it. Furthermore, I would never have gone to press without it. Nor would Vanessa and that pack of vultures she calls lawyers have waited so long to sue us. They would have swooped the minute the magazine hit the street.

But she is suing the photographer.

Guccione: Sure, for $10,000; not even enough to pay the legal fees. That suit is just a tactic, a means of employing the discovery process in law to determine whether or not we really have the release. She knows she signed it, but I have good reason to believe that she’s under the impression Chiapel lost it when he moved out of his studio. This is their way of finding out. Kind of corny and a little bit insidious, of course, but still a tactic.

Why insidious?

Guccione: Because if Tom had lost the release and we published the pictures purely on his word that a signed release did exist, they could, and no doubt would, take the position that there never was a release and sue us for the unauthorized publication of her photographs.

Isn’t that reaching a bit?

Guccione: Why else are they suing Tom and not us? Tom doesn’t have any money. They can’t collect anything from him. We’re a much more interesting target.

How do you know the release you have is real?

Guccione: Because we took the trouble to bring in two eminent handwriting experts. We left nothing to chance. Both experts checked her signature against other documents we were able to provide and both experts authenticated it. There is no question that Vanessa Williams signed that release!

Penthouse: You have been asked on numerous occasions, particularly by the press, to produce it. Why don’t you? Why don’t you settle the dispute once and for all?

Guccione: Because Miss Williams, in my opinion, cannot be trusted. That is the single, most valuable piece of evidence we have. Should they decide to sue, our case could stand or fall on the production of that document, and I’m simply not about to disclose its contents to the other side.

But why? If the release is such a crucial piece of evidence, wouldn’t showing it to the public make her go away forever?

Guccione: Not necessarily. Once you’ve seen your opponent’s defenses, you can strategically build your attack around it. For example, let’s assume they see the release and the release is dated June 1, 1983. That piece of information could be critical. Why? Because if they were so minded, they could set out to prove that she was out of town when the photographs were alleged to have been taken. A shabby trick, perhaps, but it wouldn’t be the first time such a stunt was pulled.

You don’t appear to have a whole lot of respect for her.

Guccione: Why should I? Particularly at this stage. She lied to the pageant, she lied to the public … what’s to stop her from lying to a court? She swears up and down she never signed the Chiapel release when we know that she did and she continues to threaten us with lawsuits. Not a very good record.

Couldn’t she just be a frightened little girl trying to defend what’s left of her honor?

Guccione: The image of Vanessa Williams as a naive and trusting little girl ravaged by photographers and pilloried by the big-city publisher is wearing a bit thin. How innocent can she be? One month after posing for Tom — believing, of course, that the photographs were for her eyes alone — she gets picked up in the streets of Manhattan by another photographer. Once again, in an eager sunburst of innocence and trust, she takes off her clothes and slips into a pair of handcuffs, chains, and leather harnesses — believing, no doubt, that the resulting photographs would be for her own use … to make silhouettes, I suppose. Her next step, to ensure the absolute privacy of these photographs, was to sign yet another model release. And those are the pictures on page 52 of this issue.

Didn’t she try to get them back?

Guccione: Sure. She went back to Jonathan Aaron, her new photographer, and brought her boyfriend with her. I read that he carried a kitchen knife in his back pocket, in the event that her otherwise persuasive and trusting innocence didn’t work.

Penthouse: Nonetheless, a lot of people still believe she was badly mistreated.

Guccione: By whom? Tom Chiapel, Jonathan Aaron, me? If anyone treated her badly, it was the pageant. But one has to look at the other side of the coin. How did she treat the pageant? Firstly, she entered the pageant under false pretenses. She deceived the officials by not informing them of her recent past. Remember, she was under a contractual, not to mention moral, obligation to disclose those events in her life which, if they surfaced, could prove embarrassing to the pageant. Clearly, she knew that the photographs represented a real danger. She’s a bright girl and it doesn’t take much to figure out how valuable the photographs had become now that she was Miss America. She made no effort to contact the photographers and negotiate their return. She took a chance that nothing would happen, and it did. It always does. So whereas I may not agree with the pageant or the repressive morality it promulgates, I have to agree that every man has the right to set the rules in his own home. And once you accept his hospitality, he should have every reasonable expectation that you will abide by them.

You mentioned that the press, by and large, treated you badly. How did the black press regard the incident, and did they attempt to turn it into a racial issue?

Guccione: No. Quite the contrary! The white press tried to create some kind of racial intrigue by harping on the fact that she was the first black Miss America and that, as a result of our publication of her photographs, the black community would be set back 20 years. I found that figure interesting. No one could tell me why it was 20 years and not 12 or 15 or even 30. The black press, however, with very few exceptions, took a much more balanced and philosophical view. Of course they were disappointed. She was a black achiever, glamorous and intelligent, the perfect role model for young black women competing in a predominantly white world. They were disappointed, all right, but they didn’t lash out and blame Tom Chiapel, or Penthouse, or me. “She made the mistake,” they said. “No one held a gun to her head.”

Did you get any threats?

Guccione: A few.

How many?

Guccione: About 2,000 — 2,000 death threats and about 250 bomb threats.

Weren’t you frightened?

Guccione: If I was, I was too scared to think about it.

Then you were frightened.

Guccione: Not really. I was only joking. I’ve been threatened before. It’s one of the things a public figure has to learn to live with. Besides, it’s the guy that doesn’t threaten that you have to worry about … like the lone-wolf psycho that shot John Lennon. He’s the dangerous one and he doesn’t tip you off in advance.

Did you take any extra precautions, hire more bodyguards?

Guccione: No. But I tend to be cautious anyway. I think a lot of that early bad blood disappeared the moment the magazine came out and the people had a chance to see the pictures for themselves.

How do you think they’re going to feel about the new pictures, the Jonathan Aaron bondage portfolio?

Guccione: Well, if they’ve got a sense of humor, they have to laugh.

Why laugh? Wouldn’t those who still sympathize with her take offense at what they might perceive to be harassment on the part of Penthouse?

Guccione: I doubt it. I think any lingering sympathy will evaporate the minute they see the second portfolio. No one could look at Vanessa Williams appearing to go down on Amy Grier in one issue of Penthouse and then see her regaled in handcuffs and chains in another issue and still take her “innocence” seriously.

Let’s assume for a moment that you’re absolutely right, that she knew precisely what she was doing at all times.

Guccione: Okay.

Isn’t it possible that despite her apparent awareness of what she was doing, she had no real knowledge of the potential consequences, and secondly, wouldn’t that suggest still another kind of innocence?

Guccione: Possibly, but her inability to foretell the future is not at issue. How many of us consider the consequences tomorrow of the things we do today? That’s not innocence. It’s sloppy planning or lack of interest or downright stupidity, but it isn’t innocence.

Perhaps not everyone agrees with you.

Guccione: Well, it wouldn’t be the first time.

Hasn’t it been reported that the original Chiapel portfolio was offered to Playboy at the same time it was offered to you, but Playboy turned it down, saying that they didn’t want to be known as the magazine that cost Miss America her crown?

Guccione: Bullshit! Playboy turned the pictures down for two reasons. They didn’t want to pay the price and the documentation was insufficient. I also turned them down on the lack of proper documentation. It wasn’t until I met the photographer himself that I learned a properly executed model release did exist. I saw it, sent it over to our lawyers, and had the handwriting and signature authenticated. The rest is history.

Hugh Hefner appeared on television saying, in effect, that what you had done was immoral. How did you feel about that?

Guccione: Hefner is an unmitigated hypocrite! He’s also a liar and a fool. I happened to see that little interview and I couldn’t believe my eyes. He had to be envious to the point of distraction to make such a stupid statement publicly. For the 19 years I’ve been publishing Penthouse, four in England and 15 in the United States, I have scrupulously avoided a public mention of his name. To me, it’s unethical to personalize the competition between us. Business is business and personal is something else.

Why do you think he said what he did?

Guccione: I have no idea. He must have been so eaten up with jealousy that he let his guard down, lost his composure.

Perhaps he was genuinely offended.

Guccione: The most offensive thing to Hugh Hefner was that I had the pictures and he didn’t. And what about the Suzanne Sommers episode? They had tested her years ago when she was a nobody and turned her down for not having the proper Playboy image. Once she became famous, however, they dug up the original tests and published them. They didn’t ask her permission — and furthermore, how concerned was Hefner about the possible impact on her career … especially in television, where they’re so paranoiac about sex and nudity? And what about the various policewomen, I seem to remember, and the cheerleaders and lady marines who lost their jobs because they appeared in Playboy? I didn’t see Hefner offering to help them out.

It appears that Playboy is about to publish Suzanne Sommers again.

Guccione: Perhaps she reasoned that it’s better to submit and be paid than resist, not be paid, and get published anyway.

What has the competition been like between Penthouse and Playboy?

Guccione: Lowdown and dirty … from their side, that is!

In what way?

Guccione: Lots of ways. Every time there’s something controversial in our magazine, their advertising staff cuts it out and sends it to our advertisers or makes an in-person presentation of all our so-called failings and indiscretions to the same advertiser, just like the little kid who used to run home and “snitch” on you when you said a four-letter word. That’s the mentality! Only recently, I gave an interview to one of the trade magazines about certain fundamental changes we were about to make in our publishing philosophy. The most important of these changes had to do with advertising and the fact that I intended to restrict the number of ad pages Penthouse would accept in any given issue. Among the reasons I gave was that the indiscriminate glut of advertising in most magazines was off-putting to their respective readerships. I described page after page of commercial messages as being an undifferentiated “clutter” and said that Penthouse would take the initiative in discontinuing that practice by actually limiting the number of pages it would carry. This was revolutionary, to say the least — especially to magazines like Playboy which rely so heavily on advertising income. The next thing we knew, our advertisers were getting letters from Playboy saying, “What do you think of a publisher who describes your advertising as ‘clutter’?” How sleazy can you get! That’s not competition, that’s whining and sniveling like a child in a jealous rage … that’s “snitching!”

Isn’t that what you’re doing right now — snitching?

Guccione: If it is, I’m sorry … or maybe I’m just trying to demonstrate why people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

Being a Legacy update, you probably noticed that this article originally appeard some forty years ago now. Interestingly, as Guccione Sr. predeicted, very, very few people remember the name Geraldine Ferraro, but a whole lot of people know of Vanessa Williams. … In the way of truth being stranger than fiction, the once lavish-living Bob died destitute at 79 years old in a town called “Plano” in Texas. Life can be very strange. Of course he could have missed the pain, but then he would have had to miss the dance.