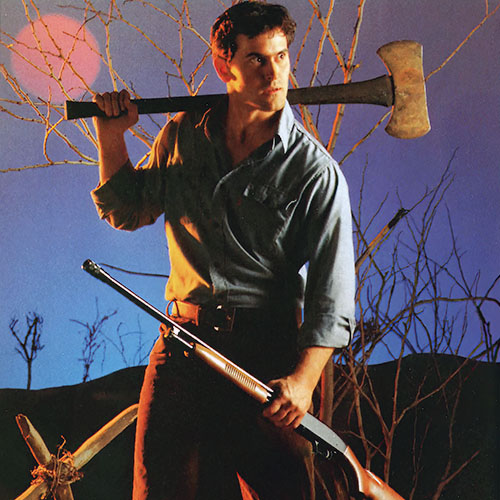

Oliver Stone’s project is masculinity.

A Stone’s Throw

Actually, Oliver Stone has many projects. Evident enough in his biography, his quest for a purposeful manhood runs through his films-those he wrote, such as Midnight Express, Scarface, and Year of the Dragon, and the scripts he directed as well: Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Talk Radio, and last year’s Born on the Fourth of July. Stylistic exercises in the ripped, gleaming details of violence (physical in the war films, and corporate in Talk Radio and Wall Street), each film looks at a man whose image of his own heroism has corroded.

Late-twentieth-century America is not the Boy Scout troop that baby boomers such as the 43-year-old Stone grew up believing it would be. The Norman Rockwell generation, where men could show strength and rightness, has faded to a nostalgic chimera, forcing its sons, in Stone’s view, to a crisis in faith. Implicitly, each of his protagonists asks not only, “What path or place can I believe in?” but “Who can I believe I am?”

The films where Stone’s chisel cuts deepest, those he wrote as well as directed, read like an agnostic’s rosary. Three of the five, Salvador, Platoon, and Born, plead for relief from doubt spawned by wars in which (American) men can’t be heroes. Our daddies fought the good fight in Europe and the Pacific, but the boys who went to Vietnam and Central America were merely consumed in orgies of murder and corruption, or became gluttons themselves. With lwo Jima ousted by My Lai (and the banal rapes of PX. scams and black markets), Stone wonders what vision of manhood or country youths can sight.

The remaining two films turn the quest to domestic arenas where men made their mark, and in doing so became bigger men. Wall Street looks at high finance, notably the place where Stone’s father made his life’s work, and calls today’s players crooked. Talk Radio looks at today’s media and finds con artists who’ll say anything for a rating. The images of Influence bottom out with clay feet, leaving younger men in the mire between selling out to corrupt careers and marginality.

Stone seems fascinated by the guys who bow to the buck-the men who murder for money, who make money for money or media for money-but he can’t countenance them. He wants to be worthy, too.

For all its wretched grit, for all the cynicism it bares, Stone’s cinema is persistently naive. He rants against the death of benevolent power because he believes it can be benevolent and that the power might have been his. Stone’s na’ivete is both well-meaning and arrogant. It’s a boyish vision and might one day limit him, but so far it has served him well. (His glee at gadgets from weaponry to electronics and at guts and gore is spankingly boyish, too.) It’s precisely his self-important idealism that allows him to speak not only to men who grew up in the fifties and sixties, but to a younger generation at the height of idealistic, arrogant na’ivete. It allows him to create roles for Charlie Sheen and Tom Cruise as well as for Tom Berenger, Willem Dafoe, and Michael Douglas, and with them, to confront a crossover crowd.

The son of a Jewish stockbroker and French Catholic mother, Stone followed prep school with Yale and dropped out of dad’s Wall Street track in the first year. He expected Vietnam would make more of a man of him than business, which he’s called “flaccid,” and “guys into their golf and fishing trips.” He taught Catholic school in Saigon in 1965, filled his head with Joseph Conrad and rugged travel, and thought about becoming a mercenary in the Belgian Congo. After a short stint back at Yale, where he wrote a book no one would publish, Stone enlisted in the Army in 1967. He refused Officer Candidate School; afraid the war would be over before he had his chance to beat the Commies, he insisted on Infantry and Vietnam.

He was a Cold War baby, as he put it; Sputnik was a “shock.” He supported Goldwater in 1964 , hated liberals, and wanted a war of his own. “It was adventure,” he has said. “It was Hemingway and Conrad, Audie Murphy and John Wayne.”

In Vietnam Stone learned to smoke cigarettes and dope, met working-class whites and blacks who introduced him to Motown, Grace Slick, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin. He fought with a sergeant and, to avoid insubordination charges, had himself shipped back to the front that, wounded, he’d just gotten away from: “I couldn’t stand that rearechelon bullshit.” He ran into the men and anti- “gook” racism, the ambushes, massacres, and “fragging” that became the basis for Platoon. “Of all U.S. casualties,” Stone says, “20 percent were accidents or people killed by our own side.”

Stone’s Cold War boosterism went into “abeyance,” as he discreetly puts it, but he had little sympathy for stateside war protesters. “There was no talk about politics over there, but those poor guys didn’t buy into any rich man’s game. They knew the score: We got fucked.” By the end of his tour of duty, Stone had been wounded twice, earning a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster. He returned to the U.S. and landed in a San Diego jail for drug possession before his father knew he was even back in the States.

Busted for carrying two ounces of marijuana over the Mexico-California border, Stone faced five to 20 years on federal smuggling charges. “There were 15,000 kids jammed into a place built for 3,000. No lawyer showed up, and these kids were telling me they had been in there for six months.” Stone swallowed his pride and called his father, who paid the court-appointed lawyer. “The moment the guy knew he was going to get paid, he showed up beaming.” The charges were dismissed. Through the seventies, when Stone tried to beat past ghosts and present frustrations with desperate carousing, he continued using marijuana, LSD, and cocaine, which became a daily habit late in the decade. In 1981, he went cold turkey; Scarface, about the coke trade in Miami, was his swan song. He believes the solution to drug abuse and gang warfare is legalization. “It’s the only way to beat it,” he has said plainly and often. “Let kids try it. Take out the allure, take out the mystique, and take off the price tag.”

After Vietnam Stone was clearheaded enough to attend film school at New York University, but spent much of his time exorcising demons. His marriage failed. In 1976 he wrote the script for Platoon, based on his “grunt” experience in Vietnam. In 1978 he wrote Born, an indirect sequel to Platoon based on the autobiography of dis-abled Marine Ron Kovic. Though Al Pacino was interested in playing the lead, the money for Born fell through shortly before shooting. The same year, Stone won a Best Screenplay Oscar for Midnight Express (directed by Alan Parker), about a young American imprisoned in Turkey on drug charges. Exasperated about the collapse of the Born project — “There was no way [the Hollywood studios] were going to make those movies, let alone let me direct them” — he decided to make a horror movie “for money.” Not only did The Hand not earn him a glove to keep him warm, he battled his way through the shooting with Michael Caine and lost the industry respect he’d garnered with the Midnight Express Oscar.

Pacino brought him onto the Scarface project; Michael Cimino wanted him for Year of the Dragon. But those were disillusioned years. In 1985 he swore he’d never go to a development meeting again. By 1986, Stone was on a roll. Salvador was a respected hit with two Academy Award nominations, and it earned him the $5 million for Platoon, which he shot in the Philippines in the midst of Aquino’s revolution. The film grossed over $140 million, earned Stone four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director, and became the Rorschach for a nation’s rage about Vietnam. Neither the films that preceded it, such as Apocalypse Now or The Deer Hunter, nor the ones that followed, Full Metal Jacket, Hamburger Hill, or Gardens of Stone, had this unleashing effect on viewers from all bands of the political spectrum and, most pointedly, on veterans.

The 1987 Wall Street caused nearly as much fuss exposing the corruption of top financial institutions and earned Michael Douglas a Best Actor Oscar. Talk Radio, based on the Eric Bogosian play about a hate-radio host, was quieter. Last year, able to raise money for projects he wanted, Stone returned to Born, focusing on Kovic’s emotional and political progress in the decade after the war that left him paralyzed from the chest down. Born begins with Kovic’s tours of duty in Vietnam, where he went to protect the free world from Communism, and killed babies and his own men instead. It follows him through his injury and the filth and impotence of the V.A. hospital, to his furious rejection of the jingoism and Catholicism of his boyhood and later to his eventual leadership-after a stint in Mexico with whores who will service “gimps” — in the veterans’ anti-war movement.

Characteristically, the camera is hectic, propulsive, and detailed, down to Kovic’s catheter tubes. Stone lurches between extreme close-ups and pans so fast they blur the screen, giving his audience the feel of Kovic’s enormous rage. He shoots police violence stateside with the same disorienting fever that he uses to film Vietnam, drawing the parallel about brutality (in the name of good, God, or order) without wasting a word. Tom Cruise, playing Kovic, turns his pretty-boy career around.

Stone’s next project was slated to be the movie version of the Andrew Lloyd Webber-Tim Rice musical Evita. When Stone and Meryl Streep signed in 1988, the film finally looked under way, until food riots erupted in Argentina and the shooting site was switched to Spain, ballooning the budget to $35 million with no cap. Then Streep dropped out of the project for “personal reasons” last September. She reconsidered ten days later, but Stone had let the production people go and was reorganizing to direct a new script of his own.

However resolved Stone is in his role as film director, his movies still scramble after heroes that aren’t. He can accept the idea that war is no longer the mold of manhood but can’t make peace with a modern masculinity that doesn’t aspire to heroism. The shock, first felt in Vietnam, that the casts have crumbled and no longer provide the stage for the makings of Great Men still jolts him. The disappointment is keener than living in reduced circumstances; he’s been denied his birthright. Boys should get to be Men, not (merely) men. Stone’s next film, due out this year, is about the Doors’ Jim Morrison, with Val Kilmer in the lead. Did rock ’n’ roll do any better for the men who tried their mettle there than the wasteland proving grounds of the military, money, and media?

I first met Stone at the Cannes Film Festival where he’d just arrived, jetlagged, from India. I saw him next a year later at the Berlin Film Festival, jetlagged from filming in the Philippines, and met him for this interview after he’d taken the red-eye from L.A. to New York to cast the Doors movie. His manner is gentle, ingenuous, even when he flirts, which he does quite well on no sleep. When something bothers him, he snaps awake and mad. Hands flailing, he scans the room and ceiling as if to find the reason the world is as it is. In a dark, rumpled sweater and what had been a five o’clock shadow the day before, he talked about the political upheavals in Eastern Europe, the wars in Central

America, and the death of Cold War thinking; American business and President Bush; American leadership and Dan Quayle; money and mores, men and (one) women; his father, Born, and his own death-wish rampages after Vietnam; the Jim Morrison movie and the pursuit of himself in all his films.

Stone: Jim [Morrison] was always a hero of mine. When I got back from Vietnam, I was 21, he was 25. I never knew him, but in the age of flower children, he was the only one who had a grasp of the dark side. The peace-and-love generation was great, but after Vietnam I wasn’t relating to the Beatles. Jim wrote about sex and death; he was saying pain is something you should carry and be proud of. It makes you. real.

When I came back from Vietnam, I didn’t run into hostility, any you-killed babies accusations. I ran into indifference. Everyone was out making a buck. The dollar in 1965 was worth something; when I got back in 1968 it was worthless because Johnson was fueling the war without raising taxes and pouring billions of dollars into the Great Society. The guys I went to school with were making a bundle. What was Vietnam to them-five minutes on the news at night? I associated business with a get-rich-quick mentality and it was not for me.

Don’t kid yourself: The country wasn’t convulsed with protests. They only happened once in a while, but there was steady accretion of wealth. I thought, people are dying over there so you guys can get rich. It took me a while to see that, especially since my dad was in business.

“If Dan Quayle is one heartbeat away from the center of power, we are in deep shit. He makes me think of The Omen: Damien gets to be president”

He was totally insulting when I got back. He said, “It wasn’t really a war, was it?-just some police action, like Korea.” I’ll never forget that. I just wanted to kill him. I wanted to tear his fucking throat out and stick a bayonet in. I was filled with images of violence, killing, and death, and no one was getting it. That’s why I was into Morrison. Woodstock I couldn’t get, but Jim I got. He was the only one talking about death. When he died, it was like when JFK died for me.

My father couldn’t cut it. He didn’t understand. The Panthers were closer to my life; they were tough. If they had asked me, I would’ve joined. I couldn’t stand the white guys, they didn’t know what they were doing. I wanted to be like the black guys who were ready to get down and fight. When we took over New York University in 1970 in protest against the bombing of Cambodia, it was such a fucking mess. There was no order, no hierarchy, no military savvy. The blacks at least said, “We have to fight.” The white guys were just, “Yeah, yeah, what do we do?” I was ashamed. I said, “Let’s get some fucking rifles and go on some rooftops and get some cops. Let’s go for Nixon. That’s the only way to end this war, to have a fucking revolution. All the rest is bullshit, this going down to Wall Street and getting beat up by construction workers bullshit.”

I wasn’t political, left or right, I just wanted to knock out the establishment. McGovern was a pansy; he wasn’t going to win. He was a loser. You want winners. If you’re gonna fight, you want to win. I wasn’t exactly into the Gandhi approach at the time.

What did you want to knock out the establishment for?

Stone: I didn’t quite get that. I said, destroy, and then we’ll see. I wanted vast change. Essentially it was, “Five to one, one to five, no one here gets out alive… You got the guns but we got the numbers… Revolution.” It’s the Morrison song. I still have a little of that in me, a strong anti-establishment tradition. But revolution is a young man’s game. Quick evolution is better.

How quick?

Stone: We better get it off quick, because if Dan Quayle is one heartbeat away from the center of power, we are in deep shit. He makes me think of The Omen: Damien gets to be president. The people who’ve had political power in this country from my generation are Oliver North and J. Danforth Quayle. North I can’t stand. He came back from Vietnam stupider than when he went the bonehead of all time. He wants to continue Vietnam. And Quayle, who was a National Guard weenie, now has more power than any of us ever dreamed of.

Where do we find a better leader?

Stone: It ain’t gonna come from politics, because by the time you get elected, you have to kiss so many asses and make so many bargains you don’t have any power.

What do you think our government is going to do in Latin America?

Stone: There was no question when I was down there shooting Salvador that we were in Honduras and ready to go into Nicaragua. Reagan was emboldened by Grenada. But Iran-contra broke in November, Platoon came out in December, and I think Reagan’s mandate was taken away from him. His last two years, 1987 and 1988, were quiet. Bush is also quiet, but what really goes on is the question. Salvador is a disaster, we keep funneling the money to the wrong guys. Nicaragua … I was just there this year. It’s on Bush’s agenda-how far he’ll go depends on how far this country will allow him.

Why do you think your generation didn’t learn more from Vietnam?

Stone: [Laughs] Because they didn’t see Salvador and Platoon. Seriously, the generation that went through Vietnam hasn’t paid close enough attention.

Get rid of the contras. Put the F.M.L.N. [the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front] in power in Salvador. Have leftist regimes in Nicaragua-embrace them because they will work. Give them money instead of trying to stop them. The people want them. There would not be a successful revolution in Salvador for ten years against a huge amount of American aid unless there was a genuine desire for change. This is what happened in Eastern Europe recently: The people got their way. They’ll always get their way. Why is America going against the people of Central America?

The principal tension of our time is between ideology and reality. Reality is working in Eastern Europe now, finally. In America, we still have this rigid ideology about Communism.

Communism is as human and multilayered as our system and has as many different forms. In fact, our system is semi-socialist. We have a state-managed economy. We bail out the savings-and-loan associations with billions of dollars. We have a defense industry which is like socialism. We bailed out Chrysler. We cannot call ourselves a wholly capitalist economy.

The world is working towards one semi-socialist system. The old definitions of capitalism and Communism are out of date and we are applying an out of-date way of thinking to Central America, costing these people enormous pain. We must update our thinking. We must think like MTV. If we’re making a deal with the East Germans and Russians, then we have to make a deal with the Nicaraguans and Salvadorans. Let reality dictate the conditions, not ideology.

You’ve been very strong in your opposition to nationalism because of the militarism, xenophobia, and racism that often go along with it. Are you concerned about a resurgence of old line nationalism in Europe, especially Germany?

Stone: Those are the problems of nationalism-always were and always will be. But what’s the alternative, the continuation of the Cold War? Do you want to keep pouring money into weaponry, the military machine, and keep a rigid map? If anything, by breaking down the old two-pronged Cold War system we’ll become more tolerant and less racist.

My hope is for an integrated planetary economy and ultimately, yes, a planetary government. Margaret Thatcher is pulling in the wrong direction when she pulls away from the European Community. The big issue now is no longer the Cold War, but the ecosystem: How do we get alternate fossil fuels or get the carbon dioxide out of the air? Only through some kind of global planning, there’s no question in my mind, some worldwide environmental planning commission and a one-currency system.

What about the state of American industry and business?

Stone: My father always said it-and I tried to hint at it in Wall Street-I think we’re in trouble because we’re not taking surplus capital and putting it into productivity. There’s a defect in our tax system that militates against productivity, because it’s easier to make money by trading without creating anything.

We have to change our tax system so it’s an incentive to create. If I sell some stock or a painting, I should be taxed at twice the normal rate because I didn’t do any work.

Bush wants to go the other way – to decrease the capital gains tax. I would double capital gains and restructure the tax system so that if you were in a legitimate business – it takes a lot of work to be specific-all the tax breaks should encourage it. My father said the strength of this country is not big business, although there is a need to have certain big businesses like steel and utilities. The strength has always been the small businessman.

The increase in corporate buy-outs and monopolies is a mistake in those industries where you don’t need it. Take the movie business. We don’t need a Paramount or a Time- Warner, Inc. The film business could be a cottage industry. You need six or seven distribution outlets, not this conglomeration.

You do independent production?

Stone: A lot. I don’t want to get stuck on movies. A much larger percentage of Japanese surplus capital goes back into production than in the U.S. I value production. That’s why I make movies. Movies, music, arms, and electronics are our biggest exports.

Who are young guys to follow? Donald Trump? The well-paid basketball player, the guy on TV who’s making it?

Who do high school kids admire? Probably all millionaires. There’s nothing wrong with making money-I have nothing against it. But not if it’s only making money. Money should be a byproduct of producing something else.

Let’s go back to movies.

Why a movie musical? It doesn’t seem your style.

Stone: I wanted to make a musical very badly after Born on the Fourth of July. But the money-Weintraub Entertainment just didn’t have it, and there were too many obstacles in all the negotiations. The budget kept escalating. I was afraid it would hit $50 million before it was all over. I didn’t want to be involved in a movie where the budget would get more publicity than the film.

What was the budget for Born On…?

Stone: Tight. Eighteen million. Nobody believed we could do it, but we did. I just heard Chevy Chase made a National [Lampoon] vacation movie for $25 million. How can they spend that much? It’s insane.

As for why a musical, each time I work I try something new. I wanted to bring back the musicals of the forties and early fifties, big spectacles. The Doors project has been around since 1986, but the rights were not secured. Nine permissions had to be gotten from various producers and the parents of Pamela Morrison and Jim Morrison and the three Doors. There’s been a tremendous battle for years over rights to the story and the music-feuds within feuds. Twelve years of legal bullshit. The rights were cleared just as Evita was falling through.

Jim’s life was a very complicated script. I’m trying to dramatize the contradictions. The dominant one is that he was part white and part American Indian-not genetically, but something in his makeup, a thread of shamanism in his personality. He had a role to fulfill in life that was Dionysian. Ultimately, he became the sacrifice. That’s as far as I’ll go.

You’ve never done a film with a strong female lead.

Stone: Like Evita? I treated her as if she were a man. I don’t differentiate between men and women that much-she was a leading character. She had redesigned herself from a poor girl to a national figure. That fascinated me, the con at the center of it.

That’s a feminist critique of my work, and too simplistic to say I deal only with men. I deal with ideas and some ideas have been embodied by men. I would like to make a film where the leading character is a woman. I just have to find the right one. Evita was it.

Your emphasis on Evita as a character who redesigned herself for a role falls in with the rest of your work. You focus on men in a crisis about who they can be in life. In Born, a young man goes to war to be a hero and discovers there’s no hero to be. The war is corrupt; his role has dried up. In Wall Street…

Stone: … the Charlie Sheen character has to decide if he’ll be his father or corrupted Gordon Gekko. In Platoon, he had to decide to go in the direction of [Willem] Dafoe or [Tom] Berenger.

As I make my films, I’m not conscious of focusing on this. You can’t say the same of Salvador… well, yes, he goes down to make a few bucks and get laid, and starts doing things his selfish side wouldn’t allow him. I guess the films are about the changing self.

Is that the idea that attracts you to your subjects?

Stone: It’s always the person. Richard Boyle, the guy Salvador is based on, is fascinating: his selfishness, corruption, charm. Though Richard himself was never redeemed in life, I saw the potential in his character for a great story of redemption, which is why I called the film Salvador, salvation. As I was researching the film, I became aware of the background of the country and I was enraged by our policies there. But it was the character of Boyle that led the way.

In Platoon, it was myself. I was plunging in to see what happened in 1967: How did I change, and why? Wall Street is interesting because my dad was on the “Street” and the film was a fantasy of what would have happened had I gone into his business. Would I have been my father’s kind of man or a Gekko?

I think there’s a lot of myself in Talk Radio, too. Part of me is interested in that show-biz aspect where you lose sight of yourself. You don’t know who you are, you don’t know what you’re saying; you’re just talking. In the end, he makes a big confession on the air about everything that he is and even he doesn’t know if he’s telling the truth.

In Born, I merged a lot of myself into Ron. We’ve known each other for ten years. I’d been hiding from the war. I never mentioned I’d been in Nam. It was ugly. I wrote about it in the mid-seventies in Platoon, but I didn’t want to talk about it or hang out with vets. I didn’t like the whole pity-me, feel-sorry-for-me concept. A lot of vets agree with me. The majority say, “We don’t want to join any fucking organization. It’s my fucking burden and I’ll carry it.” It’s a very macho attitude. When I met Ron, in a wheelchair, he brought me out of myself. We could share a common history.

There are elements of myself that I snuck into the film. For example, in the book Ron becomes politicized faster, as a direct consequence of the veterans’ hospital. In the movie he goes through his family, friends, Mexico; that’s closer to my history and to a lot of other vets’. It took us years sometimes; we didn’t join the protest movement. It took us a long time to redefine heroism.

Doesn’t the end of Born give in to a dangerous sentiment in America, that is, we — the U.S. — are really the good guys? We may have done a little wrong in Vietnam, but now we’ve proven our basic good nature because we finally did right by our Gls. Doesn’t this let us…

Stone: Off the hook?

…think that we don’t have to question government policies because, hey, we’re the good guys? We do the right thing.

Stone: You could say that the ending lets us off the hook, but nobody is going to walk out of the theater and not think about the rest of the picture. At the same time, I haven’t provoked or angered you to the point where you turn against the film.

The original script ended with Kovic fighting in the anti-war protest at the 1972 presidential convention. When I screened it that way, the audience was defeated: “You mean I sat through all this for two and a half hours and you’re going to end with a battle? There’s no hope.” You have to go out on a note of hope-it’s the Capra idea about movies. It’s corny, but it’s true. No matter what happened to Kovic, he was accepted as a hero at the 1976 Democratic presidential convention. We did not falsify those facts. And Vietnam veterans throughout the country were reintegrated into the nation a few years after that. I think Springsteen and Platoon helped take the onus off Vietnam vets.

You know, vets are hardly uniform in their views of Vietnam, and our current policies could be a lot worse. I’m involved with the East-West foundation that just built a medical clinic in Southeast Asia. We had a dinner for the project for vets from all over the country who were very proud to be reconciled with the Vietnamese-and there in the middle of it is Colonel Bo Gritz, the guy the Rambo character is based on. He’s the guy who says, “I don’t need no passport to go to Vietnam, I go when I want to go” — he means he drops into the jungle. I asked him what he goes for, and he said the big issue is our boys who are still there.

When you have that kind of jarhead mentality among some vets, you can see that we don’t have a single perception of Vietnam. We still have boneheads, the Oliver Norths and the Bo Gritzes, the Chuck Norrises.

You think Vietnam vets have been well integrated into society?

Stone: The majority, yes. There’s a huge minority that has not, but most are walking around holding jobs and very much resent the idea that Vietnam vets are any different from Korean vets or vets from World War 11. They all had problems. The Best Years of Our Lives showed it. The Korean War was the forgotten war-those vets were fucked badly. There were horrors going on in Korea. It was an undeclared war like Vietnam, an ideological war. Who started that war, that’s still a question in my mind. Think of I. F. Stone’s The Hidden History of the Korean War. The South Korean regime did a lot of shit in North Korea. It’s not as simple as one invading the other. And the treatment of vets after that war, coming home to McCarthyism, is undocumented. I’m sure there was a lot of dislocation and alienation. I don’t think the Vietnam vet has a special call on being a victim of the ideological imbalances of twentieth-century American policies.

Paul Fussell’s recent book, Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War, is about what went on in World War I I-the fear, cowardice, panic, desertion, the shooting of your own men, the imprisonments-all prefaces of Vietnam. It’s a much larger issue than Vietnam. It’s war.

Your films protest militarism, yet you’ve been criticized for using a throttling, aggressive style of filmmaking — in short, that your images and rhythms are as aggressive and angry as the militarism you’re criticizing.

Stone: David Denby [of New York mag azine] liked Born, but his biggest reservation was my direction. He thinks I’m too literal, too punchy, too much. He wants more art-he kept using the word art in his review-more detachment. I’ve heard this before and I want to throw up. I like Denby, he’s smart, but he misses the point. Detachment means Brian DePalma’s Casualties of War, which Denby loved.

And you?

Stone: I can’t comment on that film. If that’s Denby’s idea of detachment, it’s not my style. I’m engaged. What would Van Gogh say if you told him, “Hey, Vince, pull back. You’re just too tight, too intense. You’re looking in the eyeball, but you should pull back and see the face”? No. The answer is in the eyeball. I want to see it. I have the truth in the eyeball. I know it’s the truth, and if you guys don’t see it because you have to be further back because it’s punching you in the face, it’s your problem. This is my work-I can’t change the way I see the world. I’m not going to change my style to suit critics.

Maybe in 20 or 50 years, they’ll understand why I went into the eyeball. I bet my paintings sell, like Vince’s. I’m not going to be in the top ten of critics’ choices in my lifetime. I’m not a Jonathan Demme, by any means. Look at my reviews over the last 20 years they’re hilarious. My plea to critics is to realize that there are many styles of direction. There is no one way to direct a movie.

No one would suggest that you follow the direction of critics, but is it a contradiction, as some of them say, to attack explosive, knee-jerk aggression in the content of your films while reveling in an explosively angry style?

Stone: If you’re going to show anger and war, show it. Show it in all its power and glory and rapture. Why is it exciting? What makes militarism exciting to those who are militaristic? Smell the cordite, be there. Revel in it.

When Wall Street came out, one critic wrote that I was morally bankrupt because in the first part of the movie I showed the glamour of Wall Street. That’s horseshit. I’m reveling in it because my camera is showing the point of view of Charlie Sheen. At that moment I am enraptured by wealth, I am in love with it. My camera is subjective, I’m inside the character. My camera is always moving, always part of the movie. It’s not an outsider.

What made you decide to become a filmmaker?

Stone: I was always interested in writing, in poetry. I wrote a book before I enlisted-reams and reams, it was 2,000 pages. I couldn’t get it published. I went off to the war, and in Vietnam I went from being very cerebral to being visceral, practical: What are the six inches in front of my face? What do you smell in the jungle, what do you hear, what are the colors, the greens and yellows? The senses were all turned on by Vietnam.

When I came back, writing couldn’t satisfy me; there wasn’t enough physicality. Movies seemed to be the best way to combine the writing and the sensory. I had unconsciously figured this out when I got my first camera in Vietnam. I was shooting stills between rainy seasons. I bought a Super-8 when I got back, then went up to 16mm, and then [French filmmaker Jean-Luc] Godard happened, doing incredible new things with film. It had to be movies.

You said earlier that it took you a long time to redefine heroism after Vietnam. Has filmmaking solved the problem for you where Wall Street and Vietnam didn’t?

Stone: Of course. As an artist you can say things about the world that you can’t in those other jobs. We have the license, as long as we don’t abuse it, as long as we’re honestly asking ourselves why and how. Artists have that freedom, that’s why I’m interested in it. Just like Morrison said: I’m not mad, I’m interested in freedom.

You can find the complete Oliver Stone film accomplishments at IMDB, of course.